A chile pepper floats on top of a body of water. A hummingbird perches on a set of human teeth. Two tamarind plants sprout from the nose of a human face. These are the hieroglyphs that Aztec (who called themselves Mexica) scribes designed to depict, respectively, the towns of Chilapan, Huitzillac and Huaxyacac (present-day Oaxaca city).

All reflect the depth and creativity of the Aztec writing system, which is explored in a new groundbreaking book — Deciphering Aztec Hieroglyphs: A Guide to Nahuatl Writing by Gottingen University emeritus anthropology professor Gordon Whittaker.

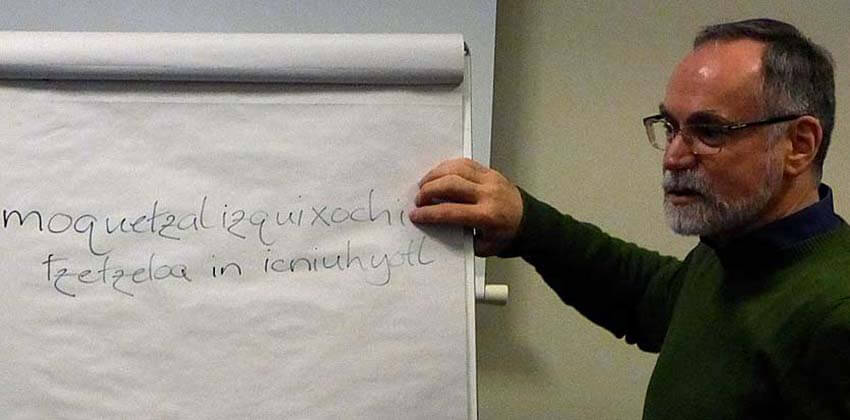

As Whittaker explained in a Zoom interview, the book is the first-ever to discuss the ancient people’s written language and its Náhuatl-speaking population.

“It’s an amazing language, highly sophisticated,” he said. “The language of a civilization, an empire. It’s been underestimated by many.”

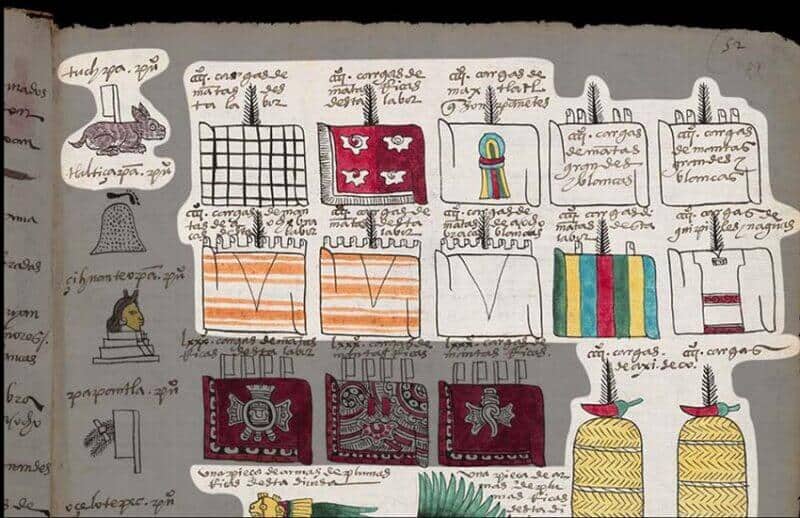

Scribes used hieroglyphs to report on the life of a civilization, from its rulers to its battles — even its taxes. They conveyed this information in a both creative and accessible way, through vibrant color and vivid imagery of people, animals and places.

The hieroglyphs populating the book include representations from sources such as the Codex Mendoza, written around 20 years after the conquest by indigenous authors and depicting Aztec history, society and daily life before Spanish colonization. That’s where Whittaker found the glyph for Huaxyacac, as well as a separate one depicting an atempanecatl, or a high official, who is shown with a set of human lips floating above his head. “Aztec names in Náhuatl, in general, for places and people were extremely creative and colorful,” he said.

He includes the Aztecs’ writing system among the great writing systems developed by ancient civilizations, including Egyptian hieroglyphs, Sumerian cuneiform and Japanese calligraphy. Yet he laments that they have been overlooked in much scholarship on the evolution of writing.

“A couple of books mention the Aztecs in one line,” he said. “A couple of others have one page or two [on] the subject. They do not really deal with the subject at all. [They think] Aztec writing was not really writing at all, something before that level. Basically, the whole field of the comparative study of writing systems ignores everything except Mayan writing in Mesoamerica. Mesoamerica has not been considered or treated well until very recently, and Aztec writing not at all.

“It’s one of the driving reasons I wrote the book … Not only was [their script] a true writing system, it was even highly sophisticated.”

Scribes built upon systems from previous Mesoamerican civilizations, including some based in the first cities of the Western Hemisphere, such as Teotihuacán and the Mayan stronghold of Chichén Itzá. The Náhuatl vocabulary eventually numbered tens of thousands of words. Whittaker notes that the writing “was not pure text; it was more like comics, comic books,” but adds, “I do not mean [it] to sound unsophisticated.”

It consisted of hieroglyphs and “annotated, pictorial representations or symbolic representations of things,” he said, such as “a tax list for the empire, all the various products that had to be sent from a province to the capital” of Tenochtitlán.

When Whittaker was growing up outside Sydney, Australia, a comic-book version of a classic of world literature introduced him to the Aztecs: his father, who served in the Australian Navy, brought home a gift from a stop in California, a children’s illustrated edition of Bernal Díaz del Castillo’s account of the conquest.

“I was just overawed by the beauty of the land and culture,” he remembered.

While Díaz del Castillo also wrote about human sacrifice, “We are kind of biased against the Aztecs and Mesoamerican people,” Whittaker said. We have a fascination about human sacrifice and ignore almost everything else.”

Whittaker became fascinated by Náhuatl while still a teenager. He tried to learn it on his own before seeking guidance from experts in Mexico. He wrote to the scholar Ángel María Garibay who, it turned out had recently died.

However, the young letter-writer received a response from one of Garibay’s students, the now-celebrated scholar Alfredo López Austin.

“He was very kind,” Whittaker recalled. “He inspired me to continue. I first got the idea that maybe it could become my life’s work.” He has been learning the language “for the better part of 50 years.”

After Whittaker landed a book contract with the British publisher Thames & Hudson in 2014, he examined how other ancient writing systems were explained to nonacademics. These included those of Egypt and China, as well as of the Maya, although he cautioned that Mesoamerican writing systems should not be assumed to be identical.

While Mayan writing predated that of the Aztecs, the Maya ended up having a give-and-take relationship with a writing system that arose around A.D. 400 in Teotihuacán, which Whittaker contends is the ancestor of the Aztec system.

“There was likely one continuous system, first developed in Teotihuacán, with an understanding of Mayan writing, that continued on to be part of all the political rises and falls over the centuries, right down to the Aztec period, the expansion of the Aztec empire,” he said.

The book identifies general principles of Mexica writing, from nouns to verbs to numbers to the calendar, all illustrated by specific hieroglyphs, some of which were direct representations of a word, such as “sun” and “tree.”

Others are composites, such as that for Chilapan, which literally means “on the chile waters.” As the book explains, chīl- means “chile” and -āpan means “on the waters of.” There’s even a hieroglyphic representation of an entire sentence — about the construction of the Great Temple of Tenochtitlán in A.D. 1487.

While Aztec writing did not end with the Spanish conquest, it suffered catastrophic losses.

“All sorts of papers and books were destroyed,” Whittaker said. “They were easy to burn, not like a clay tablet. … They were gone forever from Mesoamerica. There are just four Mayan books. How many Aztec books? None. All books of Aztec writing after the Spanish conquest [were destroyed], with one possible exception.”

This resulted in mistakes by later scribes that went uncorrected. According to Whittaker, the name of the ill-fated emperor who met with Hernán Cortés was not Montezuma but Motecuhzoma. The name of the final emperor, Cuauhtémoc, has become mistranslated.

“Cuauhtémoc’s hieroglyph shows an eagle descending, swooping down,” he said. “It’s often translated as ‘descending eagle.’ That’s not what it means at all. [It means] ‘he has descended like an eagle, swooped down like an eagle.’ It’s very symbolic.

“He would not have been given the name for that reason but he was the last emperor, who took over at a time when the Aztec Empire was in its gravest crisis and eventually defeated.”

He reflects, “It’s understandable if people who don’t know Náhuatl copy what somebody else has written or said and don’t check to see whether it’s accurate or not.”

Yet new developments augur hope for Aztec writing, Whittaker said. “There’s a huge field of scholarship devoted to Náhuatl and Aztec studies. It’s getting better all the time,” he said.

“It has an influence on Mexican society as a whole. People are reading these kinds of books — above all, indigenous people, people who are descendants of the Aztecs and their neighbors, who are also interested in the cultures of their forefathers and are reading the literature to get ideas and inspiration from that.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.