While paging through an archaeological guide to western Mexico, I came upon a cryptic reference to a long-abandoned train station near the small town of San Marcos, Jalisco, located 80 kilometers west of Guadalajara.

It said, “Yaquis were once sold here (as slaves) for 25 centavos a head . . . Around the station were located concentration camps where hundreds of indigenous people died of hunger and disease.”

When I asked my Mexican friends whether they had ever heard of such a thing, they asked me if I had ever heard of a book called Barbarous Mexico by an American named John Kenneth Turner.

I found the book and because it had been published in 1911, I was able to read all of it online at Wikisource. Despite the title, I quickly learned that the book is not an attack upon the Mexican people, but an exposé of the atrocities committed against many of them by President Porfirio Díaz during 34 years of repeated “unopposed reelection.”

One of the worst schemes of the Díaz government, says Turner, was the provocation of the Yaqui Indians to rebellion in order to clear them out of Sonora so their land — rich for both mining and agriculture — could be sold to Americans.

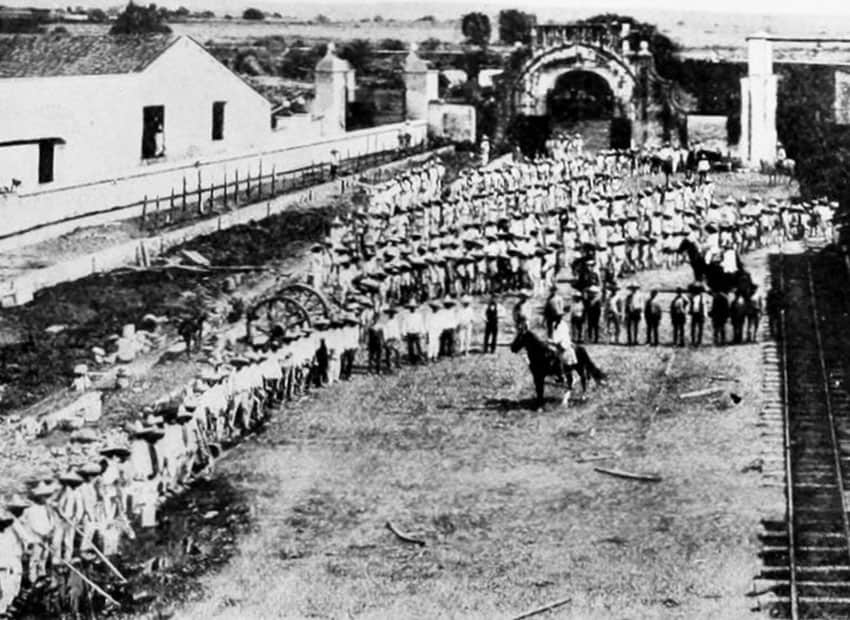

The Yaquis were put on boats at Guaymas and shipped to San Blas, where they were forced to walk over 300 kilometers to San Marcos. Here were large concentration camps where families were broken up. Individuals were then sold inside the station and packed into train cars which took them to Veracruz. Another boat ride took them to Progreso in Yucatán, from which they were taken to the plantation which would be their tomb.

John Kenneth Turner, a reporter for the Los Angeles Express, first learned about this business in 1908 from several Mexicans locked up in the local county jail.

“What are you accused of?” he asked them.

“Invading a friendly country,” they replied.

“What country is that?” he asked.

“Mexico,” they answered.

Turner inquired as to why they would want to invade their own country.

“Because the constitution has been suspended and awful things are happening.”

When he asked for concrete examples, the jailed Mexicans told him that great numbers of people were being bought and sold like cattle and forced to work on sisal plantations until they dropped dead — even though Mexico had abolished slavery many years before.

Turner was determined to see for himself and traveled to Mérida where he passed himself off as a rich man anxious to invest in the lucrative henequen hemp business.

Here he discovered that the Yaquis were indeed slaves in the worst sense of the word, beaten bloody every morning at roll call, forced to work in the blazing sun from dawn to dusk on little food, locked up every night and beaten again if they failed to cut and trim at least 2,000 henequen leaves per day.

The Yaqui women, separated from their families, were forced to “marry” Chinamen and every baby born on the plantation was worth up to $1,000 cash to the owner. At least two-thirds of the Yaquis arriving in Yucatán were dead before the end of the first year of such treatment.

Turner was able to interview some of the slaves. One man with a baby on his arm said he was plowing in his field when the soldiers came. “They did not give me time to unhitch my oxen,” he said.

“Where is the mother of your baby?” inquired Turner. “Dead in San Marcos,” replied the young father. “That three weeks’ tramp over the mountains killed her.”

Indeed, Turner’s informants agreed that “the crudest part of the trail was between San Blas and San Marcos “where women with babies fell down on the roadside, never to get up again.”

It would first appear that those who must have grown rich from these atrocities were Porfirio Díaz, his relatives and cronies, but the book points out that more than half the sisal was shipped to the U.S.A. and Turner accuses wealthy families such as the Hearsts, the Rockefellers and the Guggenheims of having profited the most from the expropriated lands of the Yaquis and Mayas as well as the “Flaming Hell” of the henequen plantations.

The Yaqui people were famed for being hard-working and strong. Between 1904 and 1909, according to Turner, around 15,000 of them were rounded up, forced along the tortuous route to Yucatán and enslaved. Despite their extraordinary strength, most of them died within the first year on the plantations, raising questions of whether they were the victims of genocide.

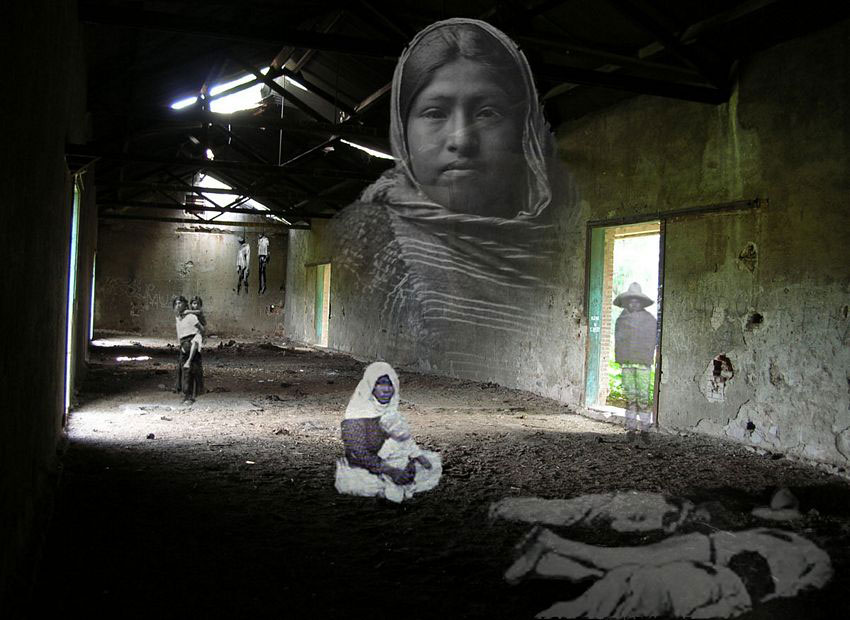

After years of abandonment, the San Marcos train station was renovated and turned into a cultural center. In my opinion, the building ought to be a memorial to the Yaquis, but there is not even a plaque commemorating the pain and sorrow suffered there.

[soliloquy id="95778"]

Today, few citizens of the area are aware of the atrocities which took place in the train station. Eighty-year-old Juan Díaz of San Marcos remembers stories of “false promises made by President Porfirio Díaz” in those times and recalls that those who took the bait “were rewarded by becoming slaves in the henequen plantations.”

Others say they remember rumors that Yaqui Indians had been sold in the place. Nevertheless, not one of the 10 histories of San Marcos found in the local library mentions a word about the mistreatment of Yaquis in the area.

Turner’s book raised eyebrows at the time of its publication and has even been called “the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of slavery in Mexico.” As it is filled with passion and indignation, it might not be considered objective. A more scholarly treatment of the same subject, however, was published by Duke University Press in 1974.

This is Development and Rural Rebellion: Pacification of the Yaquis in the Late Porfiriato by Evelyn Hu-Dehart, a professor of history at Washington University in St. Louis.

Hu-Dehart confirms the great majority of Turner’s claims, with the notable exception of his assertion that the Yaquis were essentially peaceful. “The Díaz government did not provoke the Yaqui rebellion, but inherited it,” says Hu-Dehart, who points out that the Yaquis inevitably sided with anyone fighting the authorities and refused to accept any deal giving them less than the one thing they wanted: complete autonomy in their lush corner of Sonora.

Interestingly, Hu-Dehart’s unemotional paper provides hard evidence for what might seem Turner’s most controversial accusation: that the government of Porfirio Díaz deliberately attempted the genocide of the Yaqui Indians. She quotes the words of General Lorenzo Torres to the chief of the Yaquis in 1908: “The government is . . . disposed to exterminate all of you if you continue to rebel.”

If you are traveling along Highway 4 in the state of Jalisco, perhaps visiting the Great Stone Balls of Ahualulco, or the Guachimontones (Circular Pyramids) of Teuchitlán, you might want to stop at the San Marcos train station, which is just 420 meters off that road, to reflect on the barbarous events which took place there and perhaps wander in the beautiful eucalyptus grove next to the old building.

All traces of the Yaquis’ passing have been obliterated, but their decomposing bodies probably helped give life to those tall, proud trees and perhaps they are the best memorial of all to the many souls who were murdered at San Marcos.

To find the train station, patiently type “N20.77867W104.18994” into Google Maps. It’s a 75-minute drive from the west end of Guadalajara.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area and co-author of Outdoors in Western Mexico. More of his writing can be found on his website.