So Mexican Independence Day is coming up, and if you’re not Mexican you probably wonder: why do the festivities start the night before?

Well, Mexicans’ love of partying may be part of the reason but not the main one. It has to do with how independence from Spain was achieved.

Mexico’s struggle came at a time when much of the New World was itching to throw off European rule and Spain was weak because of Napoleonic invasion and internal instability. The War of Independence wasn’t one campaign led by the same set of actors from beginning to end. It was a series of insurrections for over a decade in danger of collapsing on more than one occasion.

The first of these insurrections was led by Miguel Hidalgo, the name most strongly associated with the Independence story. He has a street named after him in the center of just about every town or city.

Hidalgo is considered to be the father of his country, but he was also a “father” in the sense that he was a priest — and despite this, because he sired five children that he acknowledged. (¡Viva México!) It is because of him that Independence Day celebrations begin late on September 15 even though the official holiday is the 16th.

At 11 p.m. on September 15, 1810, Hidalgo climbed the bell tower of the church in Dolores (now Dolores Hidalgo), Guanajuato, to call the parishioners and exhort them to overthrow the colonial government. He had been planning a rebellion with others in Querétaro, but the plot had been discovered, so his choices were to start immediately or get arrested.

Little did he know how quickly the small crowd that night would swell as it marched toward Mexico City.

With mayhem along the way, the mob/army made its way to the outskirts of the Valley of México. There they defeated the royal army at Monte de las Cruces, but in a decision that still causes debate, Hidalgo decided not to descend into the capital but rather retreat to Guadalajara.

Eventually, this decision cost Hidalgo his head, literally, as it was hung from the Alhondiga building in Guanajuato after his execution in Durango.

Hidalgo’s insurgency lasted less than 10 months, but it is the best remembered. After his death, the fighting waned in central Mexico but resurfaced elsewhere, especially in Morelos, Guerrero and Oaxaca. Several important leaders emerged, including Mariano Matamoros, Vicente Guerrero, Guadalupe Victoria and Ignacio López Rayón.

The movement, however, coalesced around José María Morelos. His importance is such that he appears alongside Miguel Hidalgo on the new 200-peso bill. He understood military tactics better than Hidalgo and brought guerilla strategies into the struggle.

Morelos and the other rebels mentioned above also had political skills. They formulated documents called “plans” to articulate their goals and rationales. This concept would be central in the chaotic century that followed Mexico’s separation from Spain.

I should mention that many current history books list Morelos as a mestizo — someone whose ancestry was a mix of Spanish and indigenous. However, at the time of his birth, he was classified as “Spanish” (likely criollo, i.e., a child who had been born in the New World whose parents had been born in Spain), even though he did have some indigenous ancestors on one side of his family.

This may reflect the attitudes of both time periods since he was a descendant of the conquistador Hernán Cortés, but today’s politics favor historical figures of indigenous or mixed heritage in a number of ways.

Morelos’s primacy lasted from 1811 to 1815. His success in the south of the country forced the Spanish viceroy to reorganize his army. But Morelos was captured, interrogated, tried and executed by firing squad. With his death, the insurgents abandoned any form of conventional warfare.

The next major phase came under the leadership of Vicente Guerrero, a mestizo with African heritage. With the death of Morelos, the viceroy thought the rebellion was all but over and even offered amnesty to insurgents. Many accepted, only to take up arms again when the opportunity arose.

This phase of the war, from 1816 to 1820, was a kind of stalemate between insurgents and royal forces. Insurgents attacked roads and convoys but launched few major attacks.

But Spain itself was embroiled in internal struggles after Napoleon was ousted in 1813. Support for royal troops in Mexico was lacking. A number of royal officers, Agustin de Iturbide among them, saw the writing on the wall, especially when a December 1820 offensive failed to decisively destroy the insurgents.

However, the insurgents were not in a great position either. Despite the fact that mestizo rebels had done most of the heavy lifting for a decade, it seemed rather likely that the criollo class would take over an independent Mexico (and indeed, that is what happened). Guerrero decided that his best bet was to join forces with Agustín de Iturbide’s faction and force the viceroy to accept an independent Mexico.

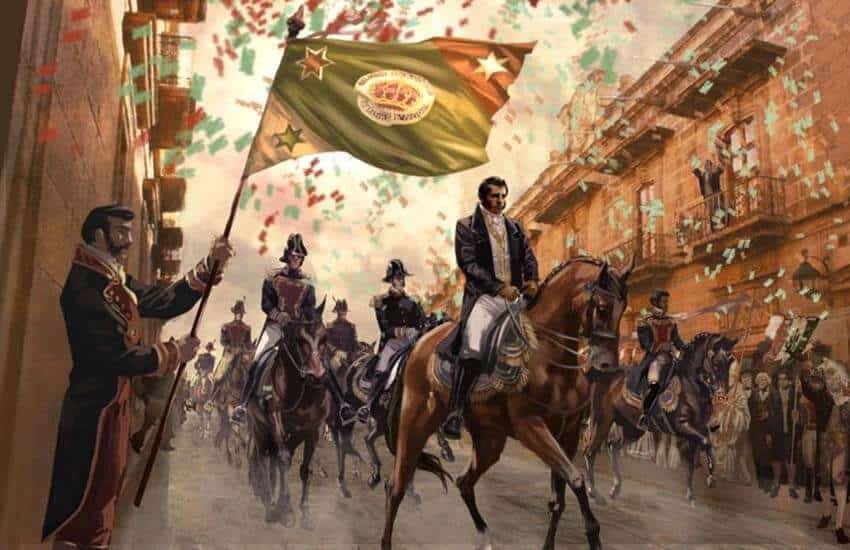

This viceroy, Juan O’Donojú, was indeed the last to rule New Spain in the king’s name. He signed the Treaty of Córdoba acknowledging Mexico’s independence on September 27, 1821, 11 years after Hidalgo rang the church bell in Guanajuato.

Spain did not immediately recognize this treaty, and it would take several more years before Mexican troops would expel the last of the Spanish army from the port of Veracruz, the same place where Cortés had invaded Mexico 300 years before.

Mexico’s Independence Day begins the night before with a reenactment of Hidalgo’s Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores). This reenactment is done at exactly 11 p.m., one of the few things that must be done on time here. When I attended my first Grito reenactment at Mexico City’s zócalo in 2005, President Fox arrived late, and the crowd responded by calling him an obscene term.

Everywhere across the country, after the leader of the country and those of the states and municipalities repeat Hidalgo’s words (more or less) and ring the bell, fireworks — and, yes, lots of drinking — commence until the early morning hours.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico 18 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.