The 140 “well-being” universities opened by the current federal government have struggled to attract students, but despite their low enrollments their funding will be nearly 1.1 billion pesos — close to US $54 million — in 2022.

President López Obrador signed a decree in 2019 to create new public higher learning institutes across the country.

The institutes, most of which are located in towns where there are no other tertiary education options, are collectively called the Benito Juárez García Universities for Well-Being (UBBJ).

Official UBBJ data cited by the newspaper El Universal shows that 28,087 students were enrolled at the universities in the first quarter of 2021 for an average of just 200 students per school. However, 50 of the universities have fewer than 100 students and some have fewer than 20.

In the latter category are the well-being university in Yuahualica, Hidalgo, which had just 13 students early last year, and that in Las Margaritas, Chiapas, which had 20.

The government hoped that student numbers would grow over time, but they have in fact declined. The total enrollment in the first quarter of 2021 was 28.3% lower than that in late 2019. In terms of student numbers, the reduction in just over a year was more than 11,000, although the government’s claim that more than 39,000 students were enrolled in 2019 has been called into doubt.

The government set a goal of reaching an enrollment of 256,000 students by the end of its six-year term in 2024, but appears to have no chance of achieving it.

Despite the decline in student numbers, funding for the schools is trending upwards. They received 987.4 million pesos last year and have a combined budget of almost 1.1 billion pesos this year, an increase of about 10%.

The government will transfer hundreds of millions of additional pesos to UBBJ students, each of whom receives a monthly scholarship of 2,600 pesos (about US $125). A total of 36 programs are taught across the 140 universities, including degrees in law, engineering, medicine and community health, tourism, social studies, forestry, food processes, sustainable development and accounting. However, each university only offers one degree program.

The quality of the education on offer was called into question in a 2020 report published by Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (MCCI), a civil society organization. In its report Universities in Limbo, MCCI said that none of the 30 UBBJ it visited in 14 states was able to award degrees to students because they were not certified by the Ministry of Public Education to do so.

Carlos Ornelas, an academic at Mexico City’s Metropolitan Autonomous University who has a doctorate in education from Stanford University, said the 140 universities constitute “a project that emerged from the imagination of the president with the intention of accommodating” poor students who were rejected by other higher learning institutes.

He predicted that enrollments won’t grow because the programs on offer at many of the universities are not attractive to potential students. In an interview with El Universal, Ornelas was also critical of the government’s spending given their low student numbers.

López Obrador’s “eagerness” to provide university places for everyone entails “too high a cost, especially considering there are campuses with 13 or 20 students,” he said.

The academic also said the government hasn’t been fully transparent with regard to enrollments.

“When this opacity ends and we start to see the data we’ll find out how many of those who enroll in these schools [actually] finish a degree,” Ornelas said.

In comparison with other public education institutions, the UBBJ are receiving preferential treatment from the government, he claimed.

“The president doesn’t like people who think,” he asserted. “That’s why there are these attacks against UNAM [the National Autonomous University] and CIDE [the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics]. This is a symptom of wanting to have everyone aligned to a single way of thinking, which is feasible with the well-being universities,” Ornelas said.

Ángel Díaz Barriga, an education expert with a doctorate in pedagogy from UNAM, said that the idea of taking higher education to isolated, marginalized parts of the country is not bad in itself but he, like MCCI, questioned the quality of instruction on offer.

The government’s mistake is focusing on increasing student numbers rather than improving the quality of the education, he said. Díaz asserted that the universities need a “complete overhaul,” as occurred with the nation’s indigenous and intercultural universities, which were given “a solid structure that allows them to function.”

Mario Lagunes, an academic at UNAM’s Social Research Institute, was also critical of the quality of education on offer at the well-being universities. He charged that the government failed to plan properly for their establishment and that the institutes don’t deserve the title of university.

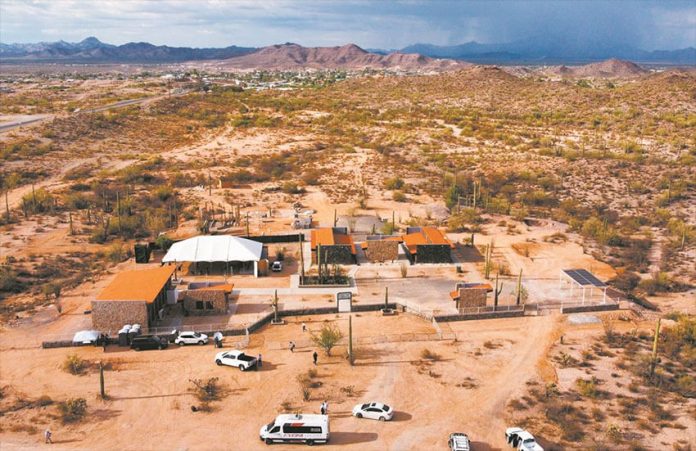

“You can’t build more than 100 universities out of nothing. … You can’t talk about universities when we know that the students occupy spaces in sports centers, commercial premises, houses, vacant lots and community centers,” Lagunes said.

With reports from El Universal