The editor and contributing author of a new book that compares and contrasts six modern-day political leaders with their counterparts from the past has charged that democratization in Mexico has given rise to a new generation of caciques, or regional strongmen (and women).

Andrew Paxman, an English historian and journalist based in Mexico, told the newspaper El Universal that state governors today could equally be described as “the new viceroys” because of the autonomy they enjoy — and power they exercise — while in government.

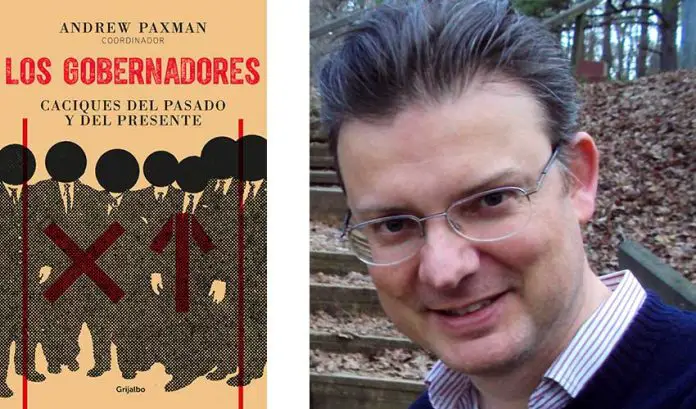

The book Los Gobernadores: Caciques del pasado y del presente (The Governors: Caciques of the past and present) examines the recent governorships of five states as well as the administration of president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador when he was mayor of Mexico City and the political reigns in days gone by of leaders in the same six entities.

The modern-day politicians included in the book were mostly chosen because at some stage in the past they showed interest in pursuing the presidency, Paxman said.

They include former governor of Hidalgo and ex-interior secretary Miguel Ángel Osorio Chong, former México state governor Eruviel Ávila, ex-governor of Puebla Rafael Moreno Valle, the now-imprisoned former governor of Veracruz Javier Duarte and the ex-governor of Yucatán, Ivonne Ortega Pacheco.

“We didn’t consider the most prominent leaders but rather those who were possible presidential candidates 15 months ago when the [book] project started. Five of the six — all except Javier Duarte — had expressed an interest in competing for the presidency and that’s interesting because it’s a sign of their growing power,” Paxman said.

“Features [of their administrations] to control the state such as selectively using violence, sometimes killing inconvenient people and a tendency to stick their hand in the money chest, to get rich from their position, were tendencies that these people admitted to.”

Paxman, a professor and researcher at the Center for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE) in Mexico City, said “this new caciquismo is the result of federal level democratization and the decentralization of power and treasury resources.”

He also said the governorship of a state was previously the “peak of power” to which a state-based politician would aspire but explained, “that’s not the case anymore, governors are aspiring to be president.”

Paxman stressed that not all the modern-day leaders profiled in the book were as cacique-like as each other in their conduct while in power, adding that López Obrador was included because of allegations that he had acted authoritatively while in office from 2000 to 2005.

However, he explained that a close examination of his administration revealed that his governance style was notably democratic.

“. . . He delegated a lot and didn’t often enforce [his views]. He didn’t try to coerce the press and refused opportunities to cultivate a corporatist power base,” Paxman said.

“Despite all the accusations and all the contradictions he [creates] himself in terms of his statements and vague proposals, the precedents we saw in his five years of government are encouraging. It appears that he will govern much more democratically than his critics say,” he added.

Among the challenges López Obrador will face as president, Paxman said, will be to promote a more democratic culture at the state level and to ensure that governors are held accountable for their actions.

He also said the president-elect will have to “implement mechanisms” to help him fight corruption, charging that he has put too much faith in the belief that he can hold himself up as an example of virtue and expect others to follow.

Source: El Universal (sp)