Mexico’s newly installed UNICEF head has wasted no time in highlighting the nation’s colossal challenges regarding children’s welfare after being named to the position Wednesday.

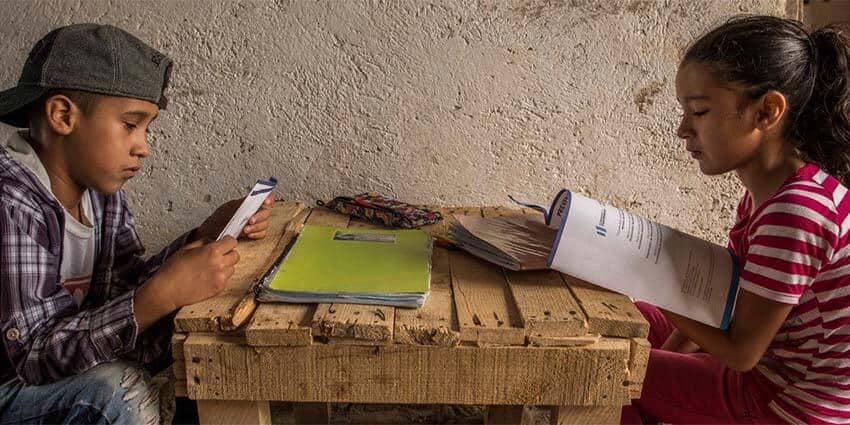

Challenges include the education of minors aged six to 18, poor nutrition, childhood obesity, and the fact that some 40% of Mexico’s children live in poverty, Guatemala native Luis Fernando Carrera Castro told the newspaper El Universal.

“There are several challenges, but those are the priorities,” he said.

Carrera had much to say in particular about Mexico’s challenges ahead in education, pointing to a UNESCO study in March that addressed Mexican K-12 students losing two years of learning due to the pandemic.

“Mexico is among the few [countries] where schools remained completely closed for more than 250 days. On Aug. 30, 2021, the Ministry of Education reopened schools, 18 months after closures,” the report said.

“In the framework of the pandemic and the closure of schools that occurred globally, it caused an enormous loss of learning, which mainly affected girls and boys who were entering the educational system in 2020 or 2021,” Carrera told El Universal.

“There will be a generation lost due to educational backwardness,” he also said.

“We must work so that basic education students, whether in rural or urban areas, can receive special attention in the recovery period, which can take up to two years, approximately,” he said.

“Girls, boys and adolescents need to go to school,” he said this week when Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard formally received him. “They need the opportunities for social contact that the school environment offers and they also need, particularly in the current context, measures to prevent and mitigate risks linked to illness and other threats to their physical and emotional well-being.”

“Avoiding [a] lag in learning, school dropout and other risks associated with lack of schooling is a national duty toward our children and adolescents, as well as an investment in the future of Mexico,” he added. “Let’s work together, all of us, to make it possible,” he said.

Carrera is also raising concerns about the pandemic’s effects on the nutrition of Mexico’s youth. Millions are plagued by poor nutrition, which in many cases leads to childhood obesity, a problem that has increased over the past two years with a dropoff in the availability of quality food.

“There is evidence that childhood obesity increased during the pandemic,” Carrera said. “Although it is a problem that existed before, it is currently more serious, so priority attention must be given to it, and that means working with educational centers that provide food, with industries that work with and distribute products for girls and boys and work hard on the issue of strengthening food quality.”

“We are talking about reducing the consumption of products that are basically processed or ultra-processed, which are the ones that do the most damage, and sugary drinks or high-calorie foods,” he added.

Carrera said that nutritional problems are just one of the many effects of poverty. And poverty, he added, “unfortunately, is stagnant in the case of Mexico” and “may have increased up to 7%” during the pandemic.

According to El Universal, 40% of Mexico’s children live in poverty, if it’s defined as not having at least one basic need not met, such as running water, decent housing or health care. If it’s based on a socioeconomic level, the newspaper said, “we are probably talking about 30% to 35% of the country’s child and adolescent population.”

“Today, the relative wealth divided by the total population of Mexico would give us a per capita income [US $8,000, according to El Universal] very similar to that of the United Kingdom in 1985,” Carrera told the newspaper. “If one looks at the social indicators at that time for children [in the U.K.], there was a significant difference from Mexico. There was much less poverty, better learning and not so much childhood obesity.”

For these reasons, he added, the problem of inequity in Mexico is immense and does not allow a large percentage of children and adolescents to fully enjoy their rights. “For some, there is too much, and for others there is little,” he said.

UNICEF, which was founded in 1946 and promotes the rights and well-being of children and adolescents in more than 190 countries, has been in Mexico for 65 years. Last month, it opened a new office in Mexicali, Baja California.

With reports from El Universal