On a good day, before the pandemic set in, José Mejía Morales earned between 150 and 200 pesos (about US $7.50–$10) selling peanuts and chapulines (roasted grasshoppers) from his two buckets.

“Now, there are days when I earn nothing, when there is no income,” says the Cholula, Puebla, street vendor.

His chapulines, he claims, are the best because they’re caught in the wild. His peanuts are also the best because they come from Chiapas. He calls himself a chapulinero — a person who sells chapulines, and corrected me when I called him an ambulante (mobile vendor) and told me he’s an itinerante — an itinerant worker. Ambulantes, he explained, have a specific spot from which they sell their products, while itinerantes roam the streets, selling their wares.

He’s roamed the streets in Cholula for 30 years now, carrying his buckets “from the pyramid to the center. I work six, seven hours a day, sometimes nine or 10. I work every day,” he says.

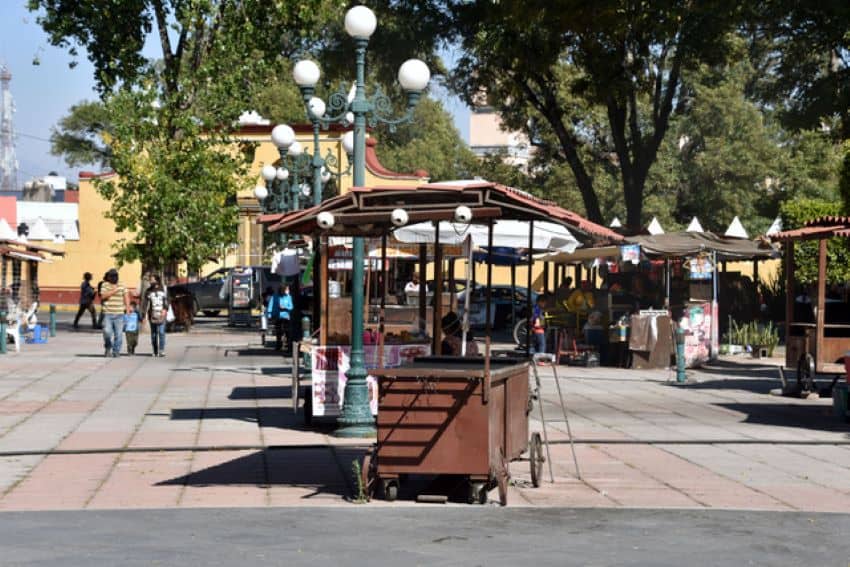

A couple of blocks away, across from Tlachihualtépetl, Cholula’s pyramid, José Felix Huítzil Guerro stands in front of the stall he’s had for 32 years, one of many that occupy one side of a small park. Like all the stalls there, his features goods that tourists are interested in: sombreros, along with a variety of Cholula souvenirs. Because of the pandemic, the municipal government is now restricting the days he can work.

“We can only work Monday to Friday,” he said.

Only three or four people a day stop by his stand now, whereas before he could expect to see 40 or 50.

“Tourism is down,” he said. “We live on tourism, and if there is none, there is no money. I don’t know how much longer we can survive.”

He’s been forced to accept financial help from his children who work in Puebla.

“It is difficult to accept their help,” he admitted, “but I have no other choice.”

All businesses in Cholula are hurting.

The municipal government closed nonessential stores for a couple of weeks in January and allowed only takeout at restaurants. Stores have recently reopened but only on weekdays. Restaurants still offer takeout and on weekdays can put a few tables out on the sidewalks. And while these businesses are struggling, most have websites allowing them to sell a few things and earn a few bucks. People like Mejía and Huítzil — itinerantes and owners of small stands — have no such options.

Mejía works in what’s known as the informal economy — the sector occupied by street vendors, young men washing windshields at intersections and people who sell flowers from wheelbarrows or tamales from small carts. Like Mejía, they earn a few dollars a day and try to scratch out a living. But that doesn’t mean they don’t have an impact on Mexico’s economy.

It’s estimated that nearly 60% of Mexican workers are employed in the informal economy and contribute about 30% to Mexico’s gross domestic product. If they’re unable to earn a living — and it’s clear that that’s becoming increasingly difficult — it’s certainly going to impact Mexico’s economy.

Mejía said that in normal times, if he didn’t have money, he would exchange things with other itinerantes and sometimes with stores.

“Maybe we can exchange for bread or tortillas with stores,” he said, “but with the pandemic, that is more difficult. I eat only one [type of] food a day now, maybe a vegetable or nopal (cactus).”

Guadalupe José Medina Tima also works in the informal economy. He’s a boleador — someone who shines shoes — and he works six days a week in the park in Cholula’s center. He carries his shoeshine box, the one bearing the name “Andy” — his daughter’s name — through the park for 11 or 12 hours a day.

“I earned 500 pesos a day before the pandemic,” he said. “Now I earn about 300. I need 300 pesos to survive, and that’s what I’m doing now: surviving.”

The 300 pesos he makes supports his wife and two young children. He’s aware of the virus and the need to wear a mask but doesn’t always do so.

“I am not afraid of the virus,” he said. “For sure, we will all die. If we do not die from the pandemic, we will die from hunger.”

Vendor stalls line another section of the park, most of them offering ice cream and candy.

“Galletas Santa Clara are very popular,” says Ascención Alcántara Vásquez, who has sold candies and cookies there since 1987. “Also, camote poblano and borrachitos nuez.”

Before the pandemic took hold, he’d sell to about 100 people on Saturdays.

“The majority were from other countries,” he said. “There was a lot of tourism. Now, tourism? Nothing. International tourism? Nothing. Now maybe 10 or 20 people and they’re almost all Mexicans.”

Like all the others I interviewed, Alcántara’s income has dropped off dramatically.

“On a Saturday, I would earn 2,000 pesos on average,” he said. “Now, maybe 100 pesos, maybe 500.”

Although the federal government has done very little to help outside of some loans to businesses, Alcántara said that Cholula’s municipal government is doing what it can to help and he greatly appreciates it.

“They gave us 4,000 pesos once,” he said. “They might do it again, but I do not know how much or when. The government is not charging for lights, for trash, for cleaning the streets. [And] they gave us some rice and beans.”

Despite the aid, he continues to struggle.

“Before, I would go to a restaurant to eat. Now, I bring my own food. I cannot buy shoes, clothes. What we earn now is to eat and nothing more.”

Although the municipal authorities have helped people like Alcántara, they’ve done nothing for intinerantes like Mejía.

“We get nothing from the government, not even water,” he complained. “I have to buy my own mask, my own gel.”

Mejía takes precautions as he totes his buckets through Cholula because he knows how dangerous the virus can be. His mother died of Covid-19 in November, followed soon after by his father and his wife.

“Of course I am afraid,” he said. “The fear is the virus, but the bigger fear is not having any kind of help and not having a vaccine or a cure. The fear is not having any food. It is for this that we work every day … for food. It is a question of getting food daily. Mexicans do not buy food for the week, we buy food for the day. That is our battle: to get food for the day.”

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer and photographer, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.