The rules governing the federal government’s youth employment program have been violated in a variety of ways, a new analysis has found, with unscrupulous individuals using the scheme for personal gain or the benefit of people and causes close to them.

The newspaper El Universal analyzed 155 citizens’ complaints about the Youths Building the Future (JCF) apprenticeship scheme, which currently pays young people a monthly stipend of 5,258 pesos (about US $260) while they complete a one-year apprenticeship with an approved employer, who also receives a government payment.

El Universal, which obtained copies of complaints from the Ministry of Public Administration (SFP) via a freedom of information request, detected at least five ways in which the program’s rules were violated in 2019 and 2020.

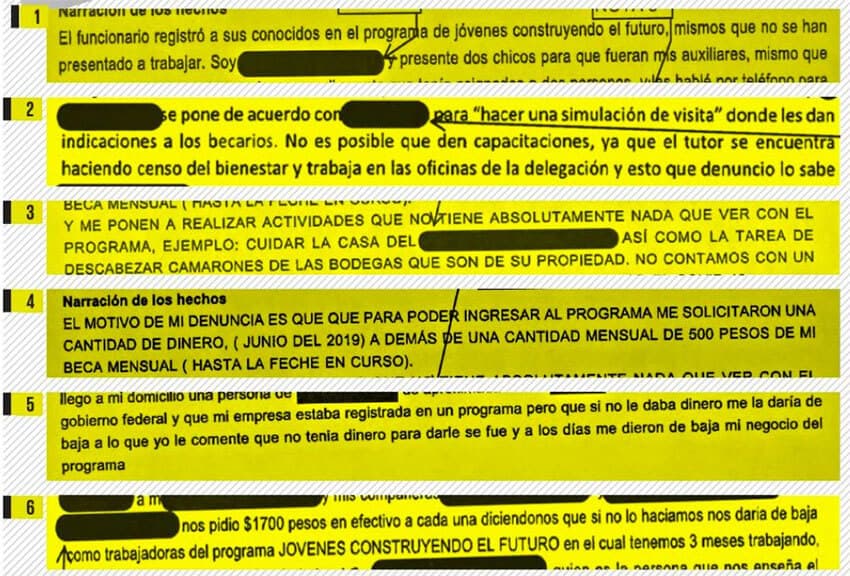

Forty-three complaints, or just over a quarter of those analyzed, were made about intermediaries who helped young people enroll in the JCF scheme in exchange for part of their monthly payment.

Apprentices were asked to pay between 800 and 2,500 pesos per month to “agents” who facilitated the online registration process. The latter figure represents almost 70% of the monthly stipend paid to program participants in 2019. Bank cards corresponding to accounts into which the payments were made were held in many cases by the agents.

El Universal said that one complaint made in 2020 described the operation of an alleged corruption network whose raison d’être was to milk the apprentices’ money. Similar networks were described in other complaints, it said, adding that companies and government officials were also involved.

“There is a leader who organizes people [in each network]. They find small [business] owners who lend themselves to the scheme. … They then find scholarship holders [apprentices] to register them in the [JCF] system. … The leader keeps the [bank] cards and when the … [monthly payment] comes he distributes the money between the young people, the [business] owners and an official who lends himself to this scheme,” one complaint said.

Another complaint said that a political group created a phony company and registered it as a JCF work center. Twenty young people were registered as apprentices and each agreed to give 2,600 pesos per month to the group. The young people weren’t actually required to work or complete any training, according to the complaint. The money the political group received was allegedly used to fund a municipal-level political campaign.

Eight other complaints said the apprenticeship program had been misused to benefit political causes.

Another way in which the rules were violated was through identity theft. In one case outlined in a complaint, the victim was the owner of a dog-grooming business.

The owner said she received a WhatsApp message in late 2019 from a person who purported to be a servant of the nation, as some low-ranking, on-the-ground federal officials are called. The message said the dog-grooming business would be removed from the JCF program unless the owner provided the details she used to register it in the scheme as well as her RFC tax number. It called for an “URGENT RESPONSE.”

The owner, whose business had been training two apprentices for four months, provided the information requested. A couple of weeks later she tried to log into the JCF platform but was unable to do so because her user name and password had been changed. She later recovered her account and discovered that her personal details had been changed and her dog-grooming business had been turned into a graphic design agency with 75 JCF apprentices.

“There is a different company registered in the program with my RFC,” she said, complaining that her personal details had been improperly used to facilitate an “improper exercise of public resources” – in other words, corruption.

El Universal said there were 15 other cases among the 155 complaints that involved identity theft, threats and harassment. The perpetrators in some cases were purportedly servants of the nation or Labor Ministry officials.

“A representative of the program showed up in my business,” one complaint said. “He asked me, ‘How many young people do you have?’ I told him three [and] he said I needed to give him 1,000 pesos for each one or he would de-register me. I didn’t take it seriously but I received an email today saying that my company had been de-registered. I don’t know what to do, I hope you can help me.”

Some young people were registered in the apprenticeship scheme without their knowledge or consent, and didn’t receive the monthly payments that the government made to accounts apparently opened in their names.

A Guanajuato university student was contacted by people who purported to be from a civil society association. They said he was eligible for a 1,000-peso monthly payment to cover his travel costs to university. He consequently provided the people with his personal details including his CURP identity number. The student later grew suspicious about the offer and decided to turn it down before he received a payment.

While completing paperwork at the Mexican Social Security Institute at a later date, he discovered he had been enrolled in the JCF scheme for three months even though, as a student, he didn’t qualify.

“I looked up JCF information on the internet and tried to register but I saw a caption that said I was already registered. I didn’t know I was a beneficiary and I haven’t received any benefit,” he told El Universal, which corroborated information in the complaints through interviews.

El Universal said that 25 of the complaints it reviewed said the JCF scheme had been used to benefit family and friends of government officials. There is plenty of scope for corruption given the size of its budget and the number of young people registered in it. The program’s 2022 budget is 21 billion pesos (just over US $1 billion) and it’s estimated that there are over 400,000 beneficiaries.

The complaints analyzed by El Universal were first made to a range of authorities before being passed on to the SFP. Some 60% were submitted via a federal government anti-corruption platform, while others were sent to President López Obrador’s office and the National Human Rights Commission. Some people even called 911 to report irregularities in the program.

The complaints the newspaper reviewed were redacted by the SFP – the government’s internal corruption watchdog – meaning that the names of people who allegedly committed the illegal acts and the locations where the wrongdoings occurred were not visible.

The Labor Ministry, which manages the apprenticeship scheme, didn’t respond to El Universal‘s request for comment on the alleged corruption, while the SFP said it is investigating over 160 cases of violations of the program’s rules. However, the ministry also said it doesn’t have the authority to take action against people who are not public servants.

Mexicans Against Corruption and Impunity (MCCI), a non-governmental organization, and the newspaper Reforma have previously reported that the JCF program is sullied by corruption.

Reforma reported last year that the scheme was used to divert large amounts of public money in the Nuevo León municipality of Linares and the metropolitan area of Monterrey, while MCCI said in a 2019 report that it had detected the probable existence of “phantom” work centers and discrepancies between the number of persons enrolled in the employment scheme and the number who are actually undertaking training.

With reports from El Universal