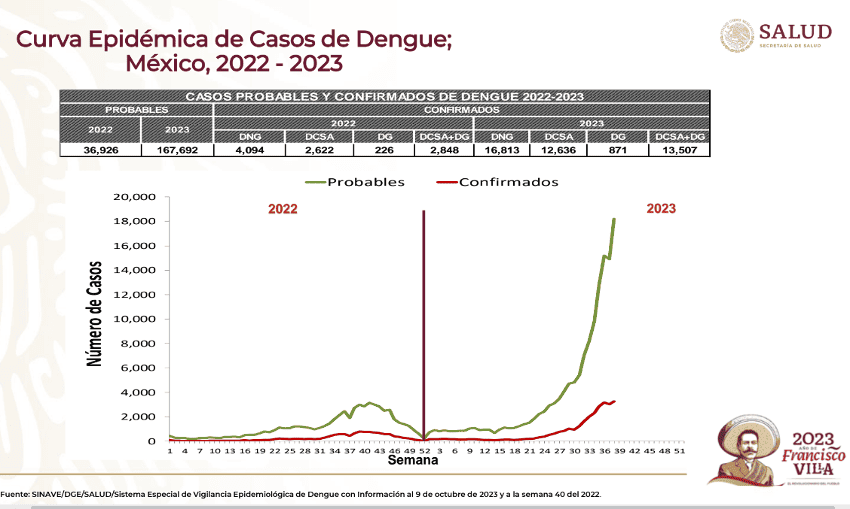

Confirmed cases of dengue have risen over 300% this year compared to 2022, with 71% of all infections detected in just five states.

According to the Health Ministry’s most recent dengue report, there were 30,320 confirmed cases of the mosquito-borne disease between Jan. 1 and Oct. 7. Confirmed cases have increased 337% this year after 6,942 were recorded in the same period of 2022.

The Health Ministry also reported that there have been over 167,000 probable cases of dengue this year as well as 48 deaths caused by the disease.

Data shows that Yucatán has recorded the highest number of confirmed dengue cases among Mexico’s 32 federal entities in 2023 with 7,523. That figure represents a whopping 4,915% increase compared to the January-October period of last year when just 150 cases were recorded in the state.

Veracruz ranks second with 6,402 confirmed cases, followed by Quintana Roo, 3,369; Morelos, 2,300; and Puebla, 2,082.

Case numbers in the five aforesaid states add up to 21,676, or 71.5% of the total.

Four other states have recorded more than 1,000 confirmed dengue cases this year: Chiapas, Guerrero, Oaxaca and Tabasco.

National case numbers have spiked in recent months amid increased precipitation in many parts of the country due to the annual rainy season.

Julián García Rejón, head of the Arbovirology Laboratory at the Autonomous University of Yucatán, told the newspaper El Economista that dengue serotype 3 (DENV-3) – one of four dengue serotypes – is currently present across the majority of Mexico.

That serotype has not previously been prevalent in Mexico and therefore many people are susceptible to becoming sick with dengue if they are bitten by a female Aedes genus mosquito carrying it. Infection with one dengue serotype provides lifelong immunity against it, but only “partial and transient protection” against the other three, according to the World Health Organization.

García said that DENV-3 likely reached Mexico from Central or South America, where there were large dengue outbreaks in the first half of the year. People with dengue caused by DENV-3 may have traveled to Mexico and subsequently infected mosquitos with that serotype, he said.

Another possibility is that mosquitos carrying DENV-3 arrived here in vehicles or on planes, García said.

The scientist said that the ongoing rainy season in various parts of the country continues to create favorable conditions for the propagation of dengue.

In Yucatán, a peak dengue infection period could be just around the corner, García warned. He said that data from previous years show that the highest number of infections in Yucatán have typically occurred in “epidemiological week 43,” which in 2023 will run from Oct. 22 to 28.

In the Americas, Aedes aegypti is the mosquito vector that is the main source of dengue transmission, according to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO).

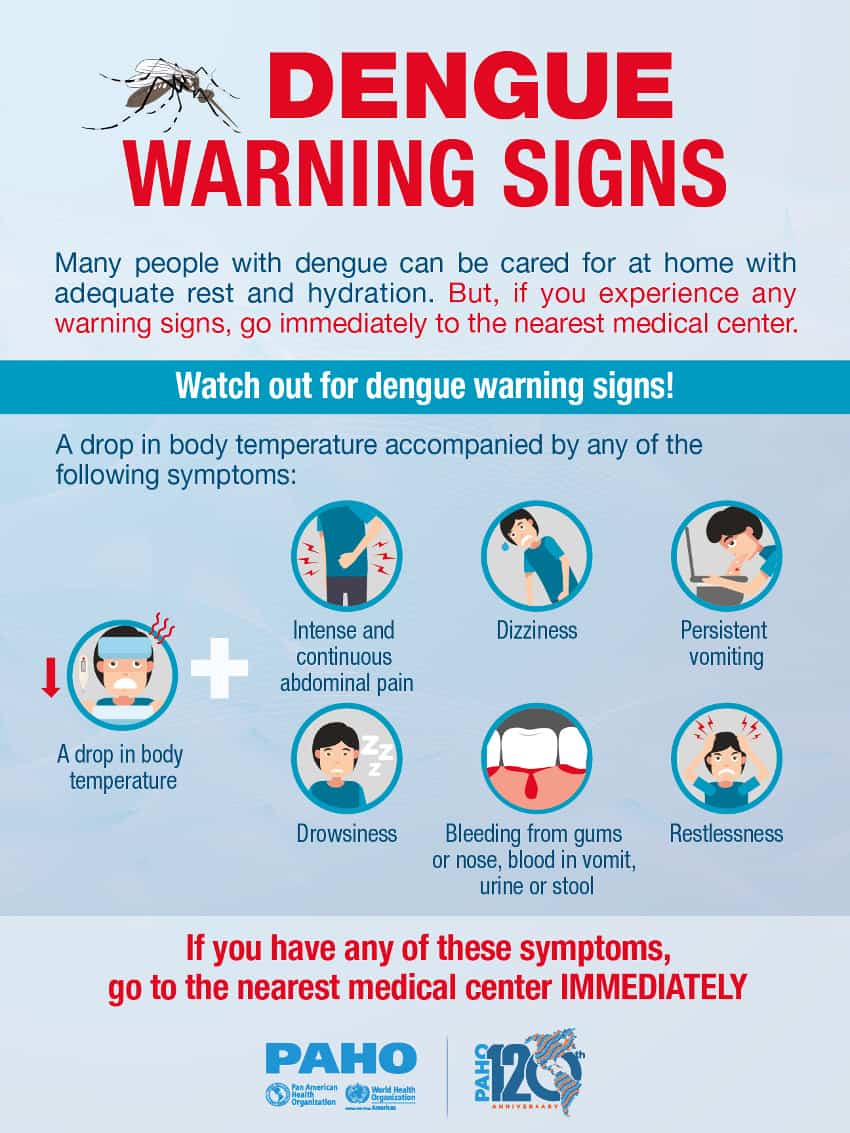

Dengue, also known as breakbone fever, is “an illness that affects infants, young children, and adults, with symptoms ranging from mild fever to incapacitating high fever, with severe headache, pain behind the eyes, muscle and joint pain, and rash,” PAHO says on its website.

“The illness can evolve to severe dengue, characterized by shock, respiratory distress, severe bleeding, and/or serious organ impairment.”

PAHO also says that “following infection with one serotype, subsequent infection with a different serotype increases a person’s risk of severe dengue and death.”

There are two different vaccines against dengue, of which one is used in Mexico, albeit not widely. Health regulator Cofepris issued a statement last month reminding health workers that the Dengvaxia vaccine shouldn’t be administered to children younger than nine.

“After detecting that this biologic was administered to children younger than nine, this health authority informs that the Dengvaxia vaccine made by Sanofi can only be prescribed for people from nine years of age to 45,” it said.

Of the more than 30,000 confirmed dengue cases in Mexico this year, 871 cases were considered serious and 12,636 were deemed cases with “signs of alarm.” The other 16,813 cases were considered “non-serious.”

Data shows that the highest number of serious and alarming dengue cases were recorded among children aged 10-14, followed by adolescents aged 15-19. Such cases were significantly higher among children and young adults than among older adults.

Morelos has recorded the highest number of dengue deaths this year with 11, followed by Yucatán and Quintana Roo, with seven each, and Guerrero and Oaxaca, with six apiece. There were 99 dengue deaths in Mexico in 2022, 85 of which occurred toward the end of the year. In the first 40 weeks of 2022, 14 deaths were attributed to dengue, 34 fewer than in the same period of this year.

Despite more than 7,500 confirmed cases of dengue and over 37,000 probable cases having been recorded in Yucatán this year, state health official Carlos Isaac Hernández Fuentes told local media that the declaration of a state of emergency is not warranted.

Governor Mauricio Vila has highlighted that authorities continue to fumigate against mosquitos that transmit dengue as well as chikungunya and zika. Trucks fitted with spray equipment are a common sight in state capital Mérida.

Authorities in other states also fumigate to reduce mosquito populations.

Ruy López Ridaura, former director of the National Center for Disease Prevention and Control Programs and now a deputy health minister, said in a meeting with state officials in late August that to reduce the incidence of dengue, zika, chikungunya and malaria, and to improve the diagnosis and treatment of those diseases, a focus on four “fundamental” things is required: “medical care, prevention and control, epidemiological intelligence and communication of risks.”

López, according to a Health Ministry statement, “emphasized the importance of making progress in what is known as vector action, which consists of efforts undertaken by health authorities to eliminate mosquito breeding sites through constant fumigation campaigns” and the removal of items in which water can accumulate.

With reports from El Economista