It’s been 10 years since poet Javier Sicilia, devastated by the murder of his son and fed up with the never-ending violence in Mexico, founded a movement for peace he hoped would help bring real change to the country.

But while he is proud of what the Movement for Peace with Justice and Dignity (MPJD) – a broad coalition of peace activists and organizations – has achieved, Sicilia concedes that the situation in Mexico now is in fact worse than it was in 2011. That was the penultimate year of the government led by former president Felipe Calderón, who launched the so-called war on drugs that has been widely blamed for triggering the rampant violence that continues to plague the country today.

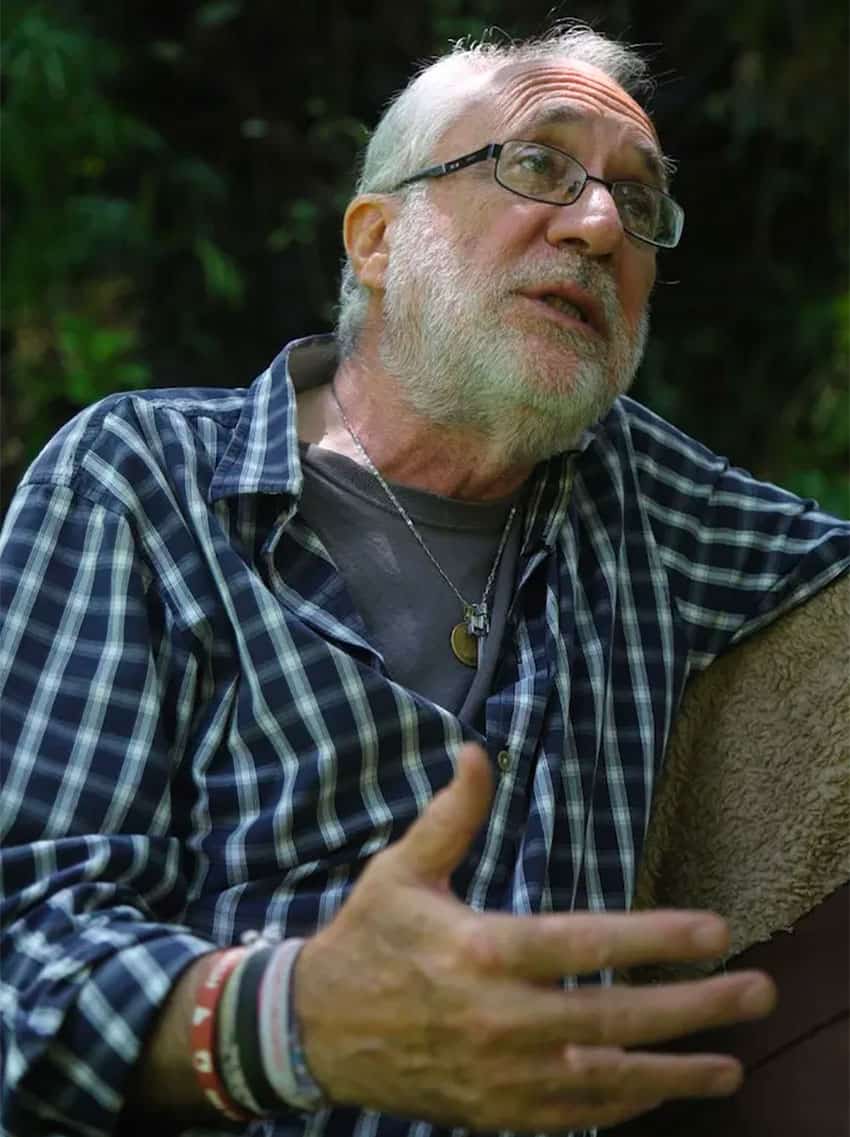

In an interview with the news website Sin Embargo, the 64-year-old poet turned activist lamented that there has been a lack of political will from successive presidents to address meaningfully Mexico’s violence problem and do what is necessary to overcome it.

He also charged that the Mexican state is “co-opted by crime” and that the federal government is unwilling to act against violence as a result.

“Despite all we [the MPJD] have done, which is a lot, what we see is a lack of political will to resolve the issues of [access to and delivery of] justice, violence, the ever-growing increase of disappearances, violations of human rights and atrocious crimes,” Sicilia said.

“We’re a lot worse off than [we were] 10 years ago. … The line between power and crime is completely erased. The state is co-opted by crime and that’s why there is a great lack of will to respond to the dignity with which the victims have expressed themselves over the course of these 10 years,” he told Sin Embargo.

Like countless other people in Mexico – where impunity for even the most heinous crimes remains rife despite President López Obrador’s pledge to eliminate it – Sicilia has not seen justice in the case of his 24-year-old son, Juan Francisco Sicilia, who along with six other people was murdered in Morelos in early 2011.

“The terrible thing is that after 10 years, [even] having the evidence and the criminals [in custody], there have not yet been any sentences,” he said.

Although violence and impunity remain rampant, the MPJD – which came to national prominence after attending talks with Calderón in Mexico City in April 2011 and organizing a 90-kilometer, three-day march for peace and justice from Cuernavaca to the capital the following month – has made victims of crime more visible to Mexican society, according to Sicilia, who described that achievement as the main legacy of the movement.

“Victims will not be silenced again, victims now have a face,” he said.

“… From the beginning of the movement, a voice was given to what was silenced and visibility was given to what was invisible – the voices of the victims. There were already collectives that had been fighting [against violence] but it was from the beginning of the MPJD that those voices … appeared to counter the atrocious discourse … [of the] administration of Felipe Calderón, which showed disdain for victims and criminalized them,” Sicilia said.

But while the MPJD, which Sicilia founded with the family members of other victims of violent crime, has helped humanize victims and make them more visible to Mexican society in broad terms, three successive presidents continued to ignored them, according to the activist.

“As it was for Calderón and [Enrique] Peña Nieto, … victims don’t exist for López Obrador; they’re sinister beings that represent the past and are to be ignored, spurned, criminalized, disappeared in graves of oblivion,” Sicilia said while speaking in Cuernavaca on Sunday at an event to mark the movement’s 10-year anniversary.

“Whether it’s the PRI, PAN, PRD, Labor Party, Green Party, Social Encounter Party, Citizens Movement or Morena, whether it’s Felipe Calderón, Enrique Peña Nieto or Andrés Manuel López Obrador, all governments and parties have been on the side of the aggressors and never the victims,” he said.

In his interview with Sin Embargo, Sicilia described Mexico’s two previous governments and the current one as disastrous but charged that the López Obrador administration has caused the greatest disappointment.

AMLO, as the president is commonly known, has betrayed victims of crime, he said, asserting that he promised to bring transitional justice and truth to Mexico but hasn’t kept his word.

Referring to the three administrations, the activist said: “We’ve encountered different discourses but the same actions.”

All of them bolstered the army (even as human rights organizations and others raised concerns about the militarization of the country), demonstrated disdain for victims and showed that they were incapable of developing “a true strategy for peace and justice,” Sicilia said.

He charged that there is “structural rotting” in both the Mexican political system and the parties that operate within it, adding that the situation has only worsened in recent years.

The rotting was never dealt with and “continued producing horror,” Sicilia said, referring to Mexico’s extremely high homicide rates.

The promulgation in 2013 of the General Victims Law, which was designed to protect the rights of victims of crime, was seen as one of the great achievements of the MPJD but Sicilia said it never worked well during the Peña Nieto administration due to a lack of political will.

“The same thing is happening with Andrés Manuel [López Obrador], who far from strengthening, reforming and prosecuting the law” dismantled the Executive Commission for Attention to Victims.

Sicilia also criticized AMLO and his government for not following up on proposals for transitional justice that were submitted to federal authorities in the wake of the November 2019 attack in northern Mexico that killed three women and six children belonging to a Mexican-American Mormon family.

In addition, he criticized López Obrador for not meeting peace activists at the end of a four-day march in January 2020 and for “manipulating” the National Human Rights Commission and leaving the National Search Commission with “minimal resources.”

Despite his criticisms, Sicilia asserted that he is not an enemy of the president but rather a citizen fulfilling his obligation to hold the government to account.

“No authority can be given a blank check; where there are mistakes, the duty of a citizen is to point them out,” he said.

Sicilia conceded that the MPJD doesn’t have the same capacity to mobilize people as it once had but contended that it still has influence and compared it to the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, a pro-indigenous rights organization that staged an uprising in Chiapas in early 1994.

“We’re the same as the Zapatistas now, we have a moral presence. There is a moral force and from that moral force we speak and we will continue pressuring [the authorities],” he said.

In addition to the high levels of violence, another thing that hasn’t changed 10 years after the foundation of the MPJD is its motto: “Estamos hasta la madre,” or “We’ve had it up to here” in polite English.

Source: Sin Embargo (sp), Reforma (sp)