On Jan. 8, the federal government presented preliminary statistics that showed that homicides declined 30% in 2025 compared to the previous year.

At face value, it certainly appears to be good news, even though homicide numbers in Mexico remain high, with more than 23,000 victims reported last year.

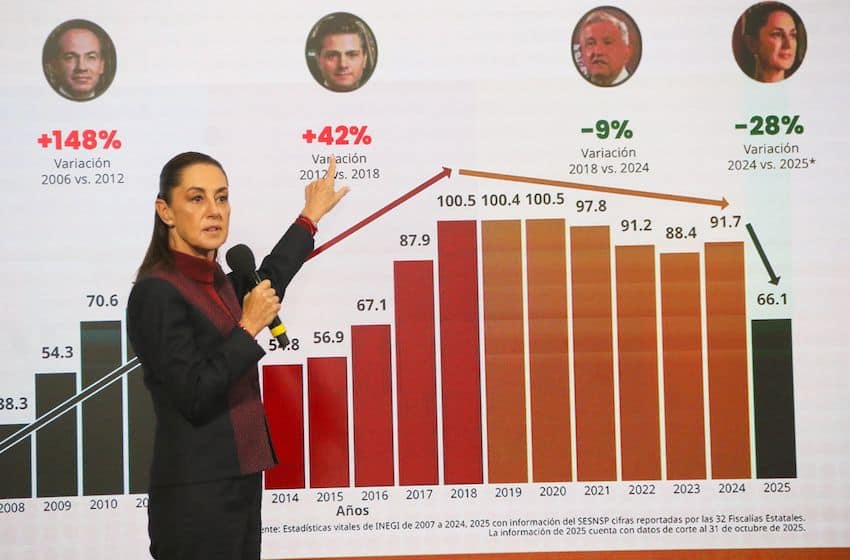

Standing next to a bar graph, Sheinbaum frequently lauds the sustained reduction in murders as a testament to the effectiveness of her government’s security strategy; on Jan. 8, she highlighted that the murder rate in 2025 was the lowest since 2016.

However, there is a growing skepticism about the accuracy of the government’s numbers.

On one hand, there are concerns that authorities in Mexico’s 32 federal entities are not accurately reporting homicides because they are incorrectly classifying some murders as less serious crimes.

On the other hand, there are claims that the decline in homicides during Claudia Sheinbaum’s presidency is related to an increase in disappearances.

It’s not the first time that homicide numbers touted by a government led by Sheinbaum have been called into question. That also happened when the current president was mayor of Mexico City, from 2018-2024.

The federal government’s homicide statistics come from the states. Are they reliable?

The homicide data the federal government presents on a monthly basis is derived from reports it receives from the Attorney General’s Offices in Mexico’s 31 states and Mexico City.

The reliability of the statistics the state-based Attorney General’s Offices provide to the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System is considered by many to be questionable.

“State Attorney General’s Offices don’t work in a vacuum,” Alberto Guerrero Baena, a public security consultant and academic, wrote in a column published by the news outlet Expansión on Jan. 9.

“They operate under budgetary, political and media pressures. When a homicide is difficult to prove or requires lengthy investigation, there is an incentive to reclassify it as injury, accidental death or a lesser crime,” he wrote.

“… An unresolved homicide looks bad in the statistics. A [fatal] injury unrelated to homicide looks better,” Guerrero wrote.

He said that “in states such as Jalisco, where multiple cartels operate, and Chihuahua, where violence is structural, these practices of reclassification are systematically documented by independent organizations.”

“The official statistics show declines [in homicides] while defense lawyers, forensic doctors and journalists document that violent deaths continue,” Guerrero wrote.

Sinaloa, one of Mexico’s most violent states and the epicenter of a battle between rival factions of the Sinaloa Cartel, is an example of another state where the incorrect classification of homicides appears to be taking place.

In a report published last November under the title “La Transformación de los Asesinatos en Propaganda” (The Transformation of Murders into Propaganda), the non-governmental organization Causa en Común also wrote about the “possible/probable reclassification” of homicides as other crimes.

“Adjacent to the category of intentional homicide, there are two other categories whose behavior has been peculiar in recent years: culpable homicide (accidents) and ‘other crimes against life and integrity,'” states the report.

“… In the past six years, the number of victims recorded in the category of intentional homicide has supposedly declined 11%. In contrast, the number of victims of culpable homicide and ‘other crimes against life and integrity’ has increased 11% and 103%, respectively,” the NGO said.

A June 2025 report by Ibero University similarly flags the “reclassification of crimes” as a possible “common strategy to reduce the visibility of high-impact crimes.”

The report also states that “the apparent reduction in homicide numbers doesn’t necessarily imply a real decrease in violence, but [could indicate] a sophisticated concealment of [intentional homicide] victims through [their classification in] other categories such as disappearances, atypical culpable homicides, unidentified deceased persons or bodies hidden in clandestine graves.”

In an interview with the EFE news agency last November, Armando Vargas, the coordinator of the security program at the think tank México Evaluá, said that to speak of a significant decline in homicides “is politically very profitable.”

However, he too noted that other “forms of violence” have increased, “amplifying suspicions” that criminal data is being manipulated.

“The expert,” EFE reported, highlighted that “some entities record more deaths from accidents (homicidio culposo) than from homicidio doloso [intentional homicide], without there being public reports of mass accidents that justify this anomaly.”

The manipulation of crime statistics by authorities in Mexico’s states is not a new phenomenon. The practice, aimed at making it appear that there are fewer homicides than there really are, allegedly dates back decades.

However, data showing a significant reduction in murders during the Sheinbaum administration — something that didn’t occur during the terms of recent past governments — has brought the issue into sharp focus.

Do disappearances conceal the seriousness of Mexico’s security situation?

A total of 34,554 people were reported as missing in 2025, according to data on Mexico’s national missing persons register.

In Sheinbaum’s first 12 months in office — Oct. 1, 2024 to Sept. 30, 2025 — 14,765 of the people reported as missing in the period remained unaccounted for when the president completed the first year of her term. That figure represents an increase of 16% compared to the final year of Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s presidency, and an increase of 54% compared to the annual average during AMLO’s six-year term.

Is this increase in disappearances related to the decrease in homicides? According to many observers, the answer is yes.

Reuters reported on Jan. 8 that government critics claim that the increase in “forced disappearances” is “masking the violence in the country.”

In an opinion article published by The New York Times in December, Ioan Grillo, a Mexico-based journalist with extensive experience reporting on organized crime, wrote that “opposition figures” assert that the reduction in homicides is “just because cartels are now disappearing more people, rather than leaving corpses to be counted.”

For its part, the news website Animal Político reported a few weeks ago that from the point of view of search collectives, “disappearance has become a criminal strategy: erase the body, dilute the crime [disappearance rather than homicide] and indefinitely extend punishment for the families.”

In its report, Causa en Común wrote that “another factor of uncertainty about the accuracy of the intentional homicide records is the increase in the number of disappeared persons” during the Sheinbaum administration.

“… Of course, an indeterminate number of people recorded as missing were murdered. Maybe for that reason, the missing person numbers don’t usually appear in the morning press conferences,” the NGO wrote.

It added: “The increase in disappearances has been of such magnitude that in some entities there has been a crossover in the records, with more reports of disappeared persons than victims of intentional homicide.”

Vargas, the México Evalúa security expert, asserted that “the federal government isn’t interested in the issue of disappearances,” even though Sheinbaum has said that attending to the missing persons problem is a “priority” for her administration.

“The disappeared are once again missing from official discourse,” he said.

Vargas said that disappearing people allows organized crime groups to “create terror” and “hide lethal violence” because “without a body there’s no crime.”

Do authorities, including the federal government, need to do a better job at locating missing persons — dead or alive — and solving such cases? According to victims’ relatives, and many others, the answer is definitely yes.

But the status quo — a significant decrease in homicides (per the government’s data) and an increase in disappearances — is a situation “in which everyone wins,” Vargas told EFE.

“With the bodies disappeared,” he said, “it is possible to maintain [that there is] a reduction in violence” — at least as measured in homicide statistics.

Vargas also said that Sheinbaum uses the data showing a reduction in homicides during her administration to “show off” to “the opposition,” her “political rivals within Morena,” Mexico’s ruling party, and Donald Trump.

The reduction in murders — as questionable as the data might be — allows Sheinbaum to “circumvent the interventionist agenda of the U.S. president,” he said.

“It’s a very perverse scenario, but politically profitable,” Vargas said.

Less flattering data

If the number of homicide victims in the first year of Sheinbaum’s presidency is added to the number of disappearances in that period, the total is 40,265.

That figure represents a decline of just 5% compared to the average annual combined total of homicides and disappearances during López Obrador’s six-year term. It represents a significant increase compared to the average number of homicides and disappearances annually in the sexenios (six-year terms) of Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-18) and Felipe Calderón (2006-12).

Of course, a 5% reduction in the incidence of these two serious crimes doesn’t sound anywhere near as good as a 30% annual decrease in homicides, as the government has recently been touting. And clearly it is not in the interests of the current federal government to dwell on — or even raise — data that shows that the combined incidence of homicides and disappearances under Sheinbaum is higher than during the sexenios of Calderón and Peña Nieto.

However, it should be remembered that whether a person is murdered or missing, the reality for the victim’s family is essentially the same — their loved one is gone.

In a perhaps flawed defense of her government, Sheinbaum said late last year that “disappearances in Mexico are linked to organized crime in the vast majority of cases,” rather than “the state, as was the case in the ’70s and even part of the ’80s.”

Still, the Sheinbaum administration — like any government — has a responsibility to provide security conditions that make it less likely that abductions will occur, no matter who is attempting to commit them.

A proposed remedy

In an article published by Animal Político on the final day of 2025, journalist Manu Ureste described a disconnect between the government’s data on homicides and the reality of the security situation Mexico faces.

“While the institutional discourse focuses on the drop in homicides, the country ended the year with nearly 14,000 people still missing [among those who disappeared in 2025], cartels operating with wartime tactics, cities trapped in internal conflicts, and local economies subdued by large-scale extortion from organized crime,” he wrote.

In a report published late last year, Causa en Común wrote that “the underestimation and distortion of crime with political purposes are of such magnitude that official reports cease to be a useful tool to design security strategies.”

The NGO also said that “the manipulation of the most sensitive information for Mexico indicates an irresponsibility that must be corrected, out of political honesty, and to acknowledge and face up to the most serious of our problems.”

So, what can be done?

In his recent column for Expansión, Guerrero Baena, the security consultant, wrote that the Executive Secretariat of the National Public Security System (SESNSP) “acts as an intermediary between state data and public opinion.”

“Theoretically, it should filter out inconsistencies. In practice, it validates what it receives. It has no investigative powers, does not break down methodologies, and does not question classifications. It is a passive receiver that becomes an active certifier,” he wrote.

In that context, Guerrero Baena proposed “four structural reforms” that he asserted could “restore credibility” to “the statistical measurement of violence.”

- The carrying out of independent audits of State Attorney General’s Offices’ crime data. Such audits would review “100% of cases” in which violent deaths are not classified as intentional homicides. When “patterns of systematic reclassification” of violent deaths are detected, the information should be referred to federal authorities. Audit results must be published on a quarterly basis.

- Reform the SESNSP to give it “independent verification” powers. Create a “statistical validation unit” with direct access to information from the Civil Registry and the Mexican Social Security Institute as well as forensic records, and investigations in prosecutors’ offices. “This unit should publish reports on methodological discrepancies found, requiring public corrections when the figures do not correspond to demographic realities.”

- Create a “national observatory of anomalous mortality” that cross-checks Civil Registry data on deaths with information from prosecutors, medical examiners and forensic medicine institutes. “This observatory would report monthly on deaths recorded as violent,” but which don’t have “corresponding investigation files, allowing for the identification of true blind spots in the system.”

- Conduct “methodologically rigorous” victimization surveys every three months in order to gauge the “lived experience” of Mexicans with regard to violence. The results of the surveys “would be published alongside” data on reported crimes, “allowing for comparison and mutual validation.” (Statistics agency INEGI already conducts a National Survey of Urban Public Security on a quarterly basis, which measures people’s perceptions of insecurity in the cities in which they live.)

In his column, Guerrero wrote that his proposals “are just the beginning of a necessary transformation.”

“The urgent task is to restore credibility. Without reliable statistics, without figures that society recognizes as reflecting reality, it is impossible to have a genuine public security policy,” he wrote.

“Mexicans deserve to know what is really happening in their cities. They do not deserve figures that reassure them with lies.”

By Mexico News Daily chief staff writer Peter Davies (peter.davies@mexiconewsdaily.com)