The small ironworking shop on the main street in San Gregorio Atlapulco is cluttered with tools, strips of metal, door and window frames.

Davíd Casteñada Aguilar, the owner, is bent over, soldering pieces on a cross that will soon be placed on a grave in the nearby cemetery.

“I usually make one, maybe two [crosses] a month,” he said. “I made seven last week and will make seven this week. I cannot make more than that because I lack the space and supplies.” His shop is crowded with unfinished projects.

“I cannot do other work now. Just crosses.” All of the crosses, he’s sure, are for the pueblo’s victims of Covid-19. “I know it is Covid,” he said, “because people act differently. Their expression is different; people look a little sadder, they wear masks and glasses, they do not shake hands.”

San Gregorio is a pueblo located in Xochimilco, one of Mexico City’s 16 boroughs. The most recent data from the municipal authorities in Xochimilco shows that the pueblo has had 90 cases of Covid-19 and four deaths. Those numbers are clearly a gross underestimate.

A month ago, I interviewed José Camacho, the owner of one of the three funeral homes in San Gregorio, and he said he’d already buried four people who had died of Covid-19. Two weeks later, a former mayordomo (a lay religious leader) told me that were three more confirmed deaths from the virus.

When told that the authorities are claiming that there have only been four Covid-19 deaths in the pueblo, Casteñada shook his head. “No, more,” he said. “They lie. There are more.” His work confirms that since he’s made 14 crosses for people who have almost certainly died from the virus in the last two weeks alone. That means a minimum of 21 deaths and that’s certainly a gross underestimate as well.

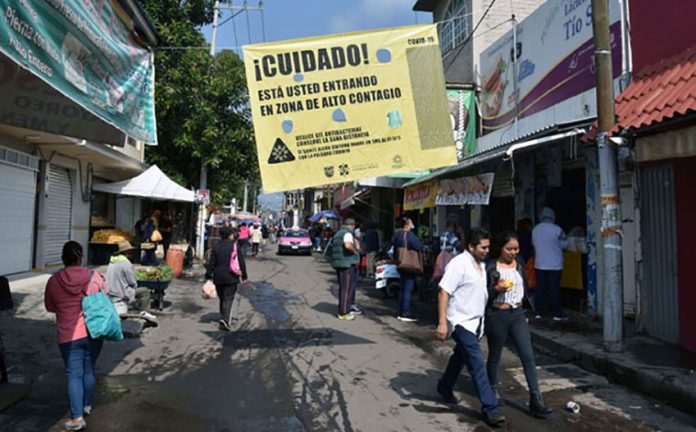

In early May, signs were placed in the pueblo’s market and in a couple of neighborhoods warning that the areas were sites of high contagion. The virus has surely settled in. But because San Gregorio has no mayor, no central authority, getting any kind of accurate information about the virus is virtually impossible.

Casteñada cuts pieces for a cross from a long narrow strip of metal and solders them together. Crosses can be simple but most are fairly elaborate. “It depends on what people want,” he said. “More elaborate ones take more time and cost more.”

A typical cross costs about 1,000 pesos (US $45). He added several flowers and other decorations to the one he was working on, painted it and, finally, added an inscription. It typically takes him about four hours to complete the work. “Usually, I would take three or four days to make a cross,” he said. “Now, they want the cross right away, the next day.”

He said most people don’t admit that the person died from Covid-19. “I think they are panicked,” he continued. “They are afraid. They lived with the person who died, maybe they were exposed.”

The mayordomo who told me about the three deaths mentioned that many people won’t admit that the deaths are caused by Covid. He wasn’t sure if it was denial or if people were afraid they’d be discriminated against if, as has happened in other places, word got out they’d been exposed.

Like everywhere in the world, the virus has changed life in San Gregorio in many ways. The large signs posted in the market inform people that they are entering an area of high contagion and that they should wear masks and clean their hands with disinfectant. There are fewer produce stalls and fewer people shopping.

The cemetery has been closed except for burials. Masses have been cancelled since late March, as were all Holy Week events in April. Normal social greetings — handshakes and hugs — are rarely seen now. Before, when clients came in to order a cross, “people would talk, we would shake hands,” said Casteñada. “Now, nothing.”

In San Gregorio, the tradition when a person dies is to have the body in the home for two days Burial is on the third day after they die and on the ninth day, a cross is placed on the grave. “Now,” said Casteñada, “it is immediately. People die, they are buried and that is it. Some people come in and ask if I already have a cross and if I do, they will buy that one.”

Despite having a big increase in orders for crosses, he’s thinking about closing his shop in a week or two, “because of the virus.”

Casteñada finished working on the cross and paused. “I do not like making these,” he said. “I do not like doing this type of work. It is not very agreeable. Really, it is like something ugly because in some cases, they are for people I know.”

Joseph Sorrentino is a freelance writer and photographer currently living in San Gregorio Atlapulco, which is part of Xochimilco.