Mexico received 111,257 asylum applications in 2022, according to data released by the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comar), purportedly the third highest number worldwide.

Although claims have fallen slightly from the nearly 130,000 registered in 2021, they are still higher than any pre-pandemic year on record. Asylum applications in Mexico rose steadily through the 2010s to over 70,000 in 2019, then dropped by almost a half during 2020, before surging again when coronavirus travel restrictions were lifted.

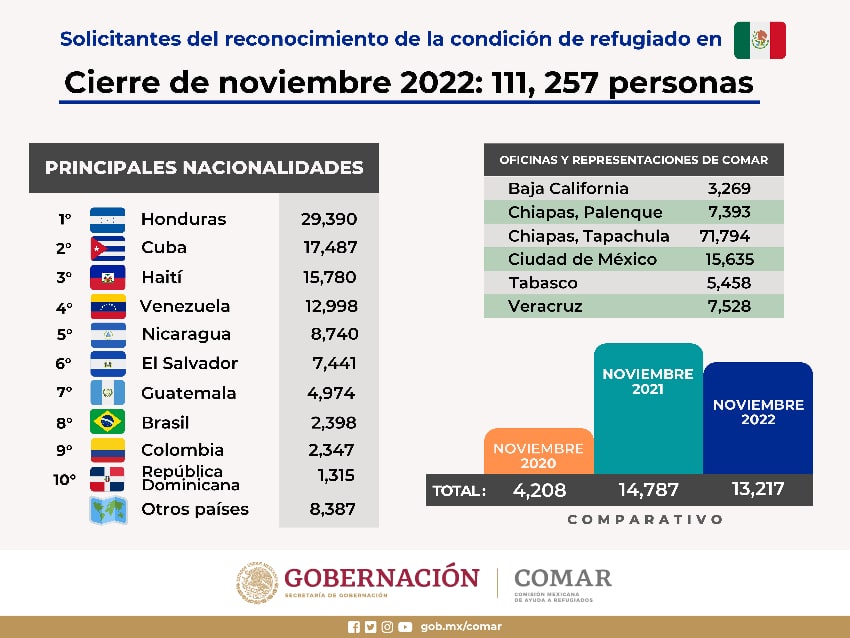

Comar said that the increase shows Mexico is now seen as a destination country by refugees around the world. Mexico has received asylum requests from 136 different nationalities, with the main countries of origin in 2022 being Honduras, Cuba, Haiti, Venezuela and Nicaragua.

“Year after year, there has been an increase in the number of people fleeing their country due to fears of persecution,” said Comar spokesperson Andrés Ramírez Silva. “Mexico ranks as the third country to receive people in need of international protection, after the United States and Germany.”

This claim appears to refer to the number of formal asylum applications received, rather than the number of refugees hosted. On the latter metric, these three countries are surpassed by countries such as Turkey, Colombia, Uganda and Pakistan, according to United Nations figures.

According to Comar, 86% of applications in Mexico over the last 10 years have been made during the current administration of President López Obrador, of which the vast majority have been granted.

“More than 83% of people in need of international protection have been recognized as refugees, and complementary protection has been given to those who have arrived at Comar in the last 10 years,” Ramírez said.

He emphasized that Mexico has been building up its asylum processing capacity in order to meet this demand. Whereas Comar only had four regional offices at the beginning of 2019 — in Mexico City; Tapachula; Tenosique, Tabasco; and Acayucan — it now has six more in Palenque, Chiapas; Monterrey, Nuevo León; Guadalajara, Saltillo, Coahuila; Tijuana and Ciudad Juárez. Plans are underway to add two more and to create new working groups to coordinate Mexico’s response.

Mexico’s growing role as a destination country for refugees comes despite its own severe problems with criminal violence. Its status as a “safe” country has also eased asylum pressure on the U.S., which has increasingly looked to traditional transit countries such as Mexico to absorb U.S.-bound migration.

Mexico abides by the Cartagena Declaration, which promises protection to anyone threatened by “generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.” The U.S. uses narrower criteria that require a person to have been individually targeted for specific reasons.

Under pandemic-era immigration restrictions known as Title 42, the U.S. can also expel would-be asylum seekers to Mexico without recourse to legal hearings. While this has created a huge backlog of migrants in camps along the U.S. border, it has likely also boosted asylum claims in Mexico. A U.S. Supreme Court ruling on Tuesday allowed Title 42 to remain in place, despite legal challenges.

Mexico also has a long history of granting asylum to political activists and deposed leaders, although it has also been known to deport foreign activists who involve themselves in Mexican politics using a longstanding law against foreign interference in Mexico’s affairs.

Notable political figures who found refuge in Mexico in the 20th century include Leon Trotsky, former Argentine president Héctor José Cámpora, the former Shah of Iran, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and Guatemalan activist Rigoberta Menchú.

More recently, Mexico has granted asylum to deposed Bolivian president Evo Morales and the family of ousted Peruvian president Pedro Castillo.

With reports from La Jornada, Infobae and ABC News