There is slightly less corruption in Mexico today than there was a year ago, according to the non-governmental organization Transparency International.

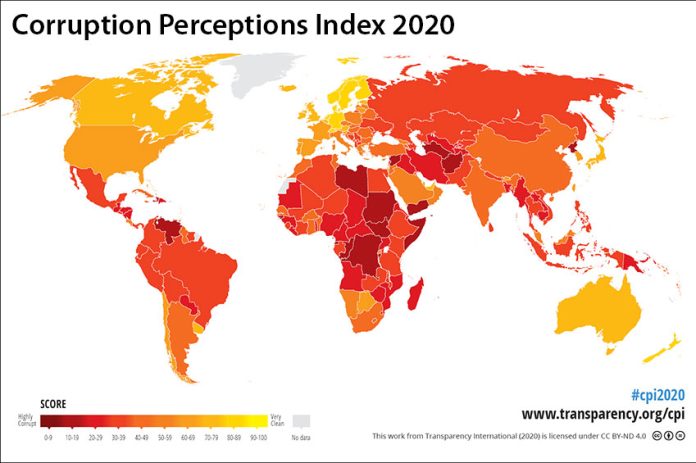

Mexico rose six places on the 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) to rank 124th out of 180 countries, sharing its position with Pakistan, Bolivia, Kyrgyzstan and Kenya.

The index is informed by corruption experts and businesspeople who offer opinions about public sector corruption in the various countries. Much of the focus in the development of the 2020 index was on corruption related to the coronavirus pandemic.

Mexico’s score on the CPI scale, in which 100 is very clean and 0 is highly corrupt, improved two points to 31 but is still well short of the global and Americas average, which was 43 in both cases.

Mexico ranked last out of the 37 OECD countries and is still four points shy of its best ever score of 35, which it achieved in 2014.

![]()

Public Administration Minister Irma Sandoval was quick to take credit for Mexico’s higher CPI score and ranking, saying that the country’s improved standing is a “clear sign that the policies driven by the Ministry of Public Administration to recover the general interest over the private interest are yielding results.”

She cited the implementation of new rules governing the declaration of assets by public officials and close supervision of public purchases during the pandemic as being among the ministry’s anti-corruption achievements.

Transparencia Mexicana (TM), the Mexico chapter of Transparency International, was less congratulatory. It said that one “delicate”issue is that penalties have still not been imposed on people allegedly involved in high profile corruption cases.

They include former cabinet minister Rosario Robles, who was allegedly involved in a government embezzlement scheme known as the “Master Fraud,” and ex-Pemex CEO Emilio Lozoya, accused of participation in corrupt activity involving Brazilian construction company Odebrecht. Both are awaiting trial.

“The risk of impunity” in corruption cases “remains latent,” TM said. The organization made four recommendations to help stamp out corruption.

Within the context of the coronavirus pandemic and its social and economic consequences, Mexico must strengthen its anti-corruption institutions, especially the Federal Auditor’s Office (ASF) and the National Institute for Transparency and Access to Information, TM said.

That is not likely to happen with the latter. The federal government has made it clear that it wishes to disband the transparency watchdog, along with other autonomous agencies, on the grounds that a government that acts morally makes it unnecessary.

TM said that the the ASF should audit public spending in real time, “with particular emphasis on expenditure on health, social programs and economic recovery programs.”

It also said that INAI, the transparency watchdog, should ensure that there is “maximum publicity” of government actions related to the pandemic.

TM’s fourth recommendation was for the federal Attorney General’s Office and institutions of justice to focus on achieving “concrete results” in corruption cases. Such results should include prison sentences for those involved, recovery of diverted resources and compensation for victims of corruption, it said.

Mexico has a lot of work to do break into the top 100 least corrupt countries on the CPI – the cutoff for the top 100 was 38 points – let alone reach the upper echelons of the index.

New Zealand and Denmark both ranked first on the 2020 CPI with a score of 88 followed by Finland, Sweden, Singapore and Sweden, which shared third place with a score of 85.

The highest ranking country in the Americas was Canada (at 11th) followed by Uruguay (21st) and the United States and Chile (25th).

In last place with a score of just 12 were Somalia and South Sudan. Syria, Yemen and Venezuela rounded out the top five most corrupt countries.

Mexico News Daily