As record numbers of migrants stream into the country, a government agency at the forefront of responding to the influx is facing a budget cut, prompting its chief to appeal to Congress for more money.

Almost 80,000 migrants, including large numbers of Haitians, have applied for asylum after crossing into the country via the southern border this year.

More than 110,000 claims are expected to have been filed by the end of the year, a figure more than 40% higher than the existing annual record.

The agency responsible for processing the claims is the Mexican Commission for Refugee Assistance (Comar), but despite the immense pressure it currently faces, the Finance Ministry last week proposed cutting its 2022 budget by more than 2% to 45.67 million pesos (US $2.3 million).

In an interview with media outlet Grupo Imagen, Comar chief Andrés Ramírez Silva said the agency needs at least 42 million additional pesos to meet the high demand for its services. That amount would allow Comar to hire an additional 148 workers to process asylum claims, he said.

In a separate interview with the newspaper El Universal, Ramírez said the agency faces a difficult situation and called on Congress, which must approve the Finance Ministry’s budget for it to take effect, to be “receptive” to Comar’s plea for additional funding.

He claimed that the resources allocated to the agency are insufficient and that the government’s proposed funding fails to acknowledge the situation it faces.

“… To determine the budget, the [current] operational capacity [of Comar] has to be taken into account because it’s [the agency] that attends to refugees,” Ramírez said before calling on the Congress to be “conscious” of its predicament.

Asked whether he expects the Congress to be understanding and increase Comar’s budget, he responded:

“I always hope [that it will be] but I know that it’s not that easy – it’s complex, but every year we’re always hoping for a better budget.”

Ramírez said funding from the United Nations refugee agency has been significant in recent years and could help Comar mitigate its shortfall but that depends on the number of migrants who arrive on the southern border with Guatemala.

He described the current situation in the southern border region – where several migrant caravans have been confronted recently by authorities after leaving Tapachula, Chiapas, before their asylum claims were processed – as unprecedented.

“The number of people arriving is really unusual. We’ve never had anything like it in the history of Mexico,” Ramírez told El Universal.

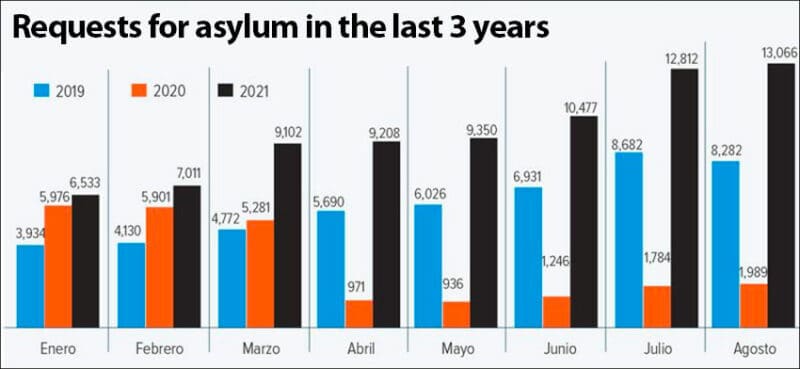

“[Arrivals in 2021] far exceed what we had in 2019, when we reached 70,400. That figure was surpassed by 10% at the end of August,” he said.

The arrival of 77,559 migrants in the first eight months of the year has placed Comar in “a really overwhelming situation,” Ramírez said, adding that the agency’s office in Tapachula – located just north of the border with Guatemala – is on the brink of collapse.

He attributed the situation to the “enormous pressure” placed on Comar by “a very large avalanche of Haitians,” who have fled the Caribbean country due to poverty and crime exacerbated by natural disasters and political unrest.

Ramírez noted that Haitians have arrived in Mexico after passing through countries such as Brazil and Chile, and claimed that they are not genuine refugees because they didn’t seek asylum in those nations.

“… They’re people who are not refugees because they don’t fit within the … [definition] of a refugee to the extent that they are coming from countries where there is not a concrete situation of persecution or violation of their rights,” he said, even though international law doesn’t explicitly require refugees to claim asylum in the first “safe” country they reach.

Although he claimed Haitians in Mexico are not genuine refugees, Ramírez said it’s “absolutely clear to everyone” that they can’t be deported to Haiti because the country’s political system is in ruins, its president was assassinated in July and it suffered a devastating earthquake in August.

“The situation is extremely complicated and what they’re seeking are migratory alternatives [to claiming asylum in the first country they reach]. … Nevertheless, we have to attend to them, that’s what the law establishes. We are attending to them, but people of many other nationalities are also arriving,” Ramírez said, referring to migrants from Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Venezuela and Cuba.

He said the number of Haitians who have arrived in Mexico this year is already triple the number that arrived in 2020.

“Due to the pandemic there was a significant decrease in migrant numbers [in 2020] for practically all nationalities but one of the important exceptions was Haiti. There was a record of 5,957 [Haitian] asylum seekers in 2020 but … in the first eight months [of 2021] … we had triple that number with 18,883,” Ramírez said.

“The issue is the bottleneck that Tapachula represents, because that’s there where the vast majority of people enter [the country], 70% [of migrants] are concentrated in Tapachula. … We’ve increased our personnel, we’ve had a lot of support from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees,” he said, explaining that the agency has provided resources to employ more Comar staff and train them.

However, more personnel are needed, Ramírez added, highlighting that staff members with Haitian Creole language skills are in particularly short supply.

“The lack of translators is an additional complication … that we don’t have with the majority of other asylum seekers who speak Spanish. … The Haitians speak Creole [but] we don’t have many people who speak Creole. We have four interpreters but that doesn’t allow us to keep up. We’re going to have more interpreters, who will arrive in the coming days. We’re going to have a total of seven,” he said.

“… [The lack of interpreters] slows down the [asylum seeking] process. … It’s a very delicate matter, we’re talking about people’s lives. However, the Mexican authorities clearly understand that we can’t deport … these people to their country of origin.”

That leaves Mexico in a difficult position because it is also facing pressure from the United States to stem the flow of migrants to its southern border.

One option is to deport Haitians to another country, as Mexico did on the weekend by sending some 150 back to Guatemala, according to migrant advocacy group Pueblos Sin Fronteras. But those migrants will in all likelihood enter Mexico again.

Another option is to resettle Haitians in Mexico in cities such as Mexico City and Tijuana, where there is already a community of Haitian migrants. But that alternative would not necessarily stop Haitians from seeking asylum in the United States, and if they do so in large numbers, Mexico runs the risk of once again upsetting its powerful northern neighbor (as occurred in 2019), even with a more migrant-friendly president in the White House.

With reports from El Universal, Excélsior, La Jornada and El Economista