Record amounts of sargassum – a seaweed that emits a foul odor when it decomposes – have washed up on the coastline of Quintana Roo in March and April, according to the head of the state’s sargassum monitoring network.

“What we’re seeing is that the massive arrivals of sargassum came much earlier than in other years,” Esteban Amaro, a marine biologist and director of the Quintana Roo sargassum monitoring network, told the news website Animal Político.

In previous years, large amounts of the seaweed didn’t reach the Quintana Roo coast until June or July, he said. This year, however, it began washing up in January, while quantities never seen before arrived in March and April, Amaro said.

Some 6 million tonnes of the seaweed washed ashore in March, up from 4 million tonnes in February, he said.

“In other words there was a large increase and in April it will probably be even greater. The figures tell us that this year will be a very big sargassum year,” Amaro said.

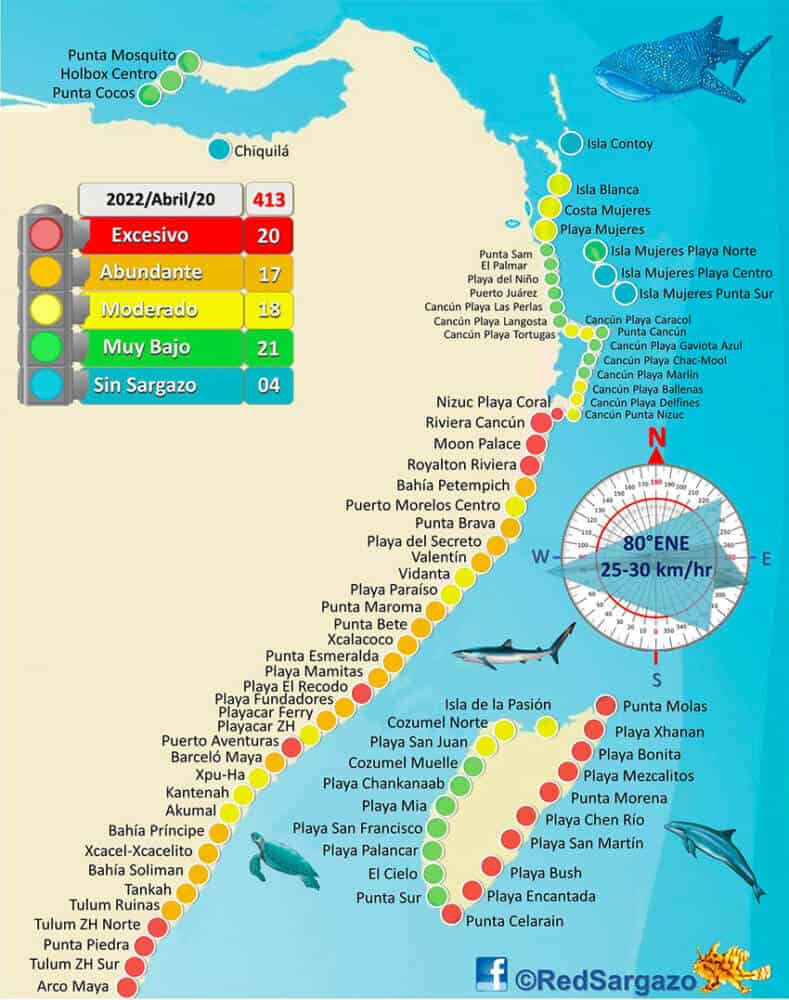

A map published Wednesday by the monitoring network shows that there are currently 20 beaches in Quintana Roo with excessive amounts of sargassum, including 10 on the east coast of Cozumel, an island off the coast of Playa del Carmen. Most of the other 10 are in Tulum and Cancún.

An additional 17 Quintana Roo beaches have abundant amounts of the smelly, brown seaweed, while 18 have moderate amounts, the map shows.

Amaro said the monitoring network warned at the start of the year that large amounts of sargassum would reach the coast this year but authorities “didn’t do anything to prevent this situation.”

“We have seen for years that the [anti-sargassum] strategy doesn’t work – over and over again the same deficiencies have been on display. For example, we’ve already seen that the barriers don’t work because the sargassum goes over [them]. They’re barriers designed for the contention of oil spills,” he said.

The navy uses sargassum-gathering vessels to remove the seaweed before it reaches the shore, but the amount extracted is dwarfed by the quantity that washes up on Quintana Roo’s famous white sand beaches every sargassum season.

The navy removed 1,483 tonnes from the sea last year, a 173% increase compared to 2019, but still only a very small fraction of the total quantity of the weed that reaches the shore. That means that most sargassum removal work happens on shore, with government workers as well as people employed by beachfront hotels doing much of the work manually.

Instead of having an anti-sargassum strategy whose central component is removing the weed from beaches, efforts should be focused on installing longer and more robust barriers at sea, Amaro said. Such barriers would assist the navy’s collection efforts, he added.

Amaro said the positioning of barriers should take sea currents into account so that they are effective in diverting sargassum back out to sea.

“I always say, ‘what is from the sea should go to the sea.’ Why do we want to remove a tremendous amount of … seaweed [on land]? To contaminate the beaches, jungle and sea? We’ve already seen that isn’t working. We have to rethink the strategy,” he said.

Laura Artemisa Patiño, president of the environmental organization Moce Yax Cuxtal, agrees. “What we’re asking is that the sargassum be collected at sea because the [environmental] impact is much less,” she said.

“Sargassum on the coast becomes mud and the white sand stops being sand because it [becomes] mud, which causes the entire surrounding ecosystem to die. That’s why the first alternative has to be offshore collection,” Artemisa said.

José Burgos, a fisherman and president of a Playa del Carmen fishing cooperative, lamented the impact that excessive sargassum has on the local economy.

“They didn’t resolve this matter in past administrations and now we’re still waiting for something to be done because this affects all of us: restaurateurs, hoteliers, those who give massages on the beach and those of us who have tourist boats,” he said.

“… The foreign tourist is not used to these conditions and can even get sick from breathing the air,” Burgos said.

In July last year, numerous civil society organizations, including Moce Yax Cuxtal, launched an online petition under the title “SOS. We’re sinking in sargassum! Its efficient management in the Mexican Caribbean is urgent.”

The change.org petition, which attracted support from almost 25,000 people, called on all three levels of government to attend to the sargassum crisis through the implementation of 10 different measures, among which were the sufficient allocation of resources for the installation of barriers and the promotion of the use of sargassum for commercial and industrial purposes.

But the response from municipal, state and federal authorities was unsatisfactory, said Fabiola Sánchez, a representative of a Puerto Morelos citizens group that supported the petition.

“They dedicated themselves to passing the buck to one another,” she told Animal Político. “The feeling is that we’re still buried in sargassum. There’s very little progress, … a lot of hot air, a lot of noise but scant action.”

With reports from Animal Político