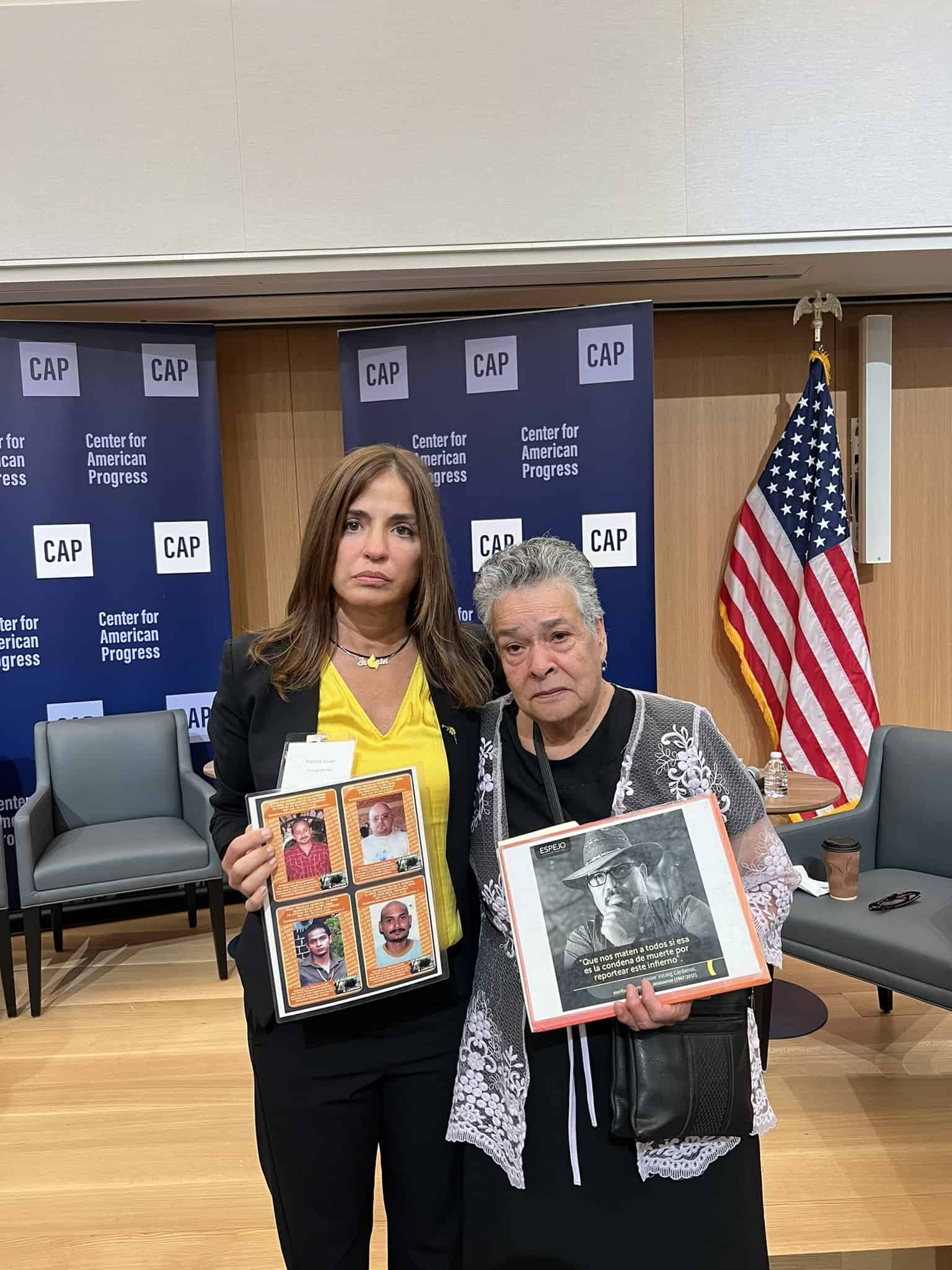

For over a decade, María Herrera Magdaleno has been searching for four of her eight children.

To help find them, she created a national network of local collectives to teach people how to investigate a loved one’s disappearance. She has met with Pope Francis, and in November, she sued the Mexican state in the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for its failure to investigate her sons’ disappearances.

Her leadership in a movement described by Time magazine this month as one “no one wants to join,” earned her a spot on the list of the most influential people of 2023 — alongside the likes of the rich and famous: King Charles III, Beyoncé and Elon Musk.

How did a 73-year-old Mexican woman from a small village in Michoacán end up meeting with world leaders, taking on her government in international court and on an international magazine’s radar?

“She is an extremely powerful woman, and she is a woman who has the ability to connect, to raise awareness, to transmit things that are not easy at all,” Montserrat Castillo, an activist who has known Herrera for a decade, told The New York Times in November.

Herrera, known affectionately as Doña Mari, is from Pajacuarán, a pueblo located at the northeastern edge of Michoacán. After her divorce, as she found herself a single mother raising her eight children and two stepchildren, she used that inner strength to start a business selling clothes, before eventually moving into metals. Her two sons, Raúl, 24, and Jesús Salvador, 24, joined her as the business succeeded and expanded. Things were looking up.

Then, on August 28, 2008, Raúl and José Salvador failed to return from a trip to the neighboring state of Guerrero. When they didn’t return, Herrera told the Times that she felt an overwhelming sadness come over her and she began to cry, sensing that “something terrible was happening.”

Neither her two sons nor their five other companions on the trip were ever seen again.

Herrera began a tireless search after a lack of support from local authorities. Her efforts eventually took her to Congress in Mexico City, where she also filed a complaint in the federal Attorney General’s Office, thanks in part to a congresswoman from Guerrero who lent her a car.

After two years of fruitless searching, tragedy knocked at her door again: her sons Gustavo, 28, and Luis Armando, 24, disappeared on a business trip to Veracruz. Later, a nephew and one of her grandsons also went missing.

According to information obtained by Herrera and her family, all four of her sons’ disappearances were abetted by local police, who had ties with organized crime.

In 2011, less than a month into the disappearances of Gustavo and Luis Armando, the newspaper Excelsior interviewed Herrera.

“What is our crime?” she asked the reporter. “To be from Michoacán? To be from humble origins? To be hardworking people?”

That year, Herrera joined a protest in Morelia, Michoacán, led by poet Javier Sicilia – who lost his own son to gang violence. There, she spoke before a crowd.

“I heard a shivering scream as they yelled at me: ‘You are not alone! You are not alone!’. They said that several times,” Herrera told the Times.

This sense of connection fueled her to organize conferences where women from all over Mexico learned from anthropologists and forensic experts how to look for signs of disturbed earth that might point to a clandestine grave and how to identify human remains. She also approached universities to convince them to teach students how to look for missing people.

In her years of searching, Herrera has found many graves. However, none of the remains she’s discovered have belonged to her sons.

Fifteen years into her search, her work has provided visibility for Mexico’s tragic crisis of disappearances: according to Mexico’s National Search Commission, more than 112,000 people are listed as missing in the country. And that doesn’t include the doubtless thousands around the country who have never been formally reported missing because of a lack of trust in government agencies.

Herrera is not planning to quit — neither in the search for her missing relatives, nor in helping other Mexicans with missing relatives.

“A mother’s heart is in each of her children,” she told the Times. “Losing them is the worst thing that can happen to you.”

With reports from The New York Times, El Financiero and Time