In southern Mexico, as in other similar climatic zones throughout the tropics, an extraordinary feature of the environment works tirelessly away upon the coast. Across countless marine shorelines and river estuaries you’ll find them doing what they can to reverse man-made climate damage. Here are the world’s greatest carbon scrubbers; their value, until recently, has been unquestionable.

The mangroves that exist in the tropical climes of the Caribbean and Central America are a vital feature of the region’s natural arsenal against carbon — aquatic trees that are adapted to harsh coastal conditions and absorb carbon dioxide for long-term storage, a unique process that makes them some of the most valuable resources in tackling the carbon crisis.

Their ability to effectively filter polluted seawater as well as oxygenate the air led to them being declared a protected entity, beyond the reach of large-scale companies capable of mass deforestation of areas heavily populated by mangroves.

Since then however, the conversation around the preservation of these sites has begun to regress, the tipping point being when President López Obrador offered the green light to Pemex to begin construction on a US $8-billion oil refinery over mangroves in Dos Bocas, Tabasco.

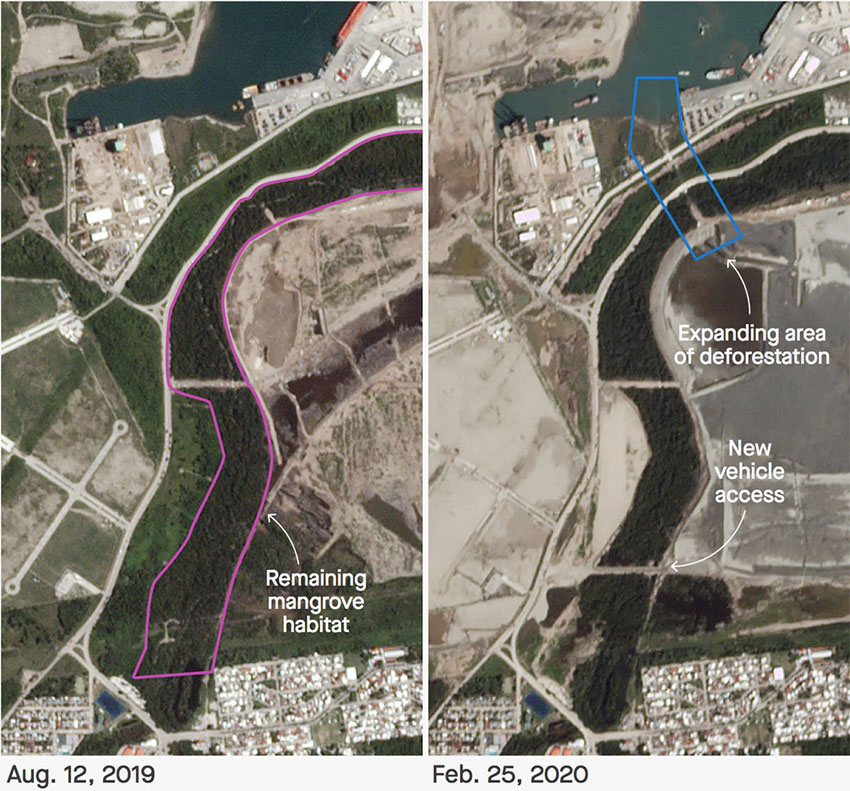

Following a disappointing downturn for Pemex amid plunging oil prices and ebbing investor confidence, AMLO — as the president is popularly known — hurriedly approved the project in his home state. Almost immediately following the go-ahead, large swathes of mangroves began to vanish from satellite imagery.

Seemingly ignoring the imposition of a $700,000 fine from the National Security, Energy and Environment Agency (ASEA), the third-party incriminated continued to plow through the protected areas. Following a “conditional permit” to proceed with the project, Pemex was made aware that all further development was dependent on the immediate halting of mangrove deforestation.

But in an almost incestuous continuation of the government’s relationship with its state oil company, a blind eye has been turned to further pillaging of the mangroves on Tabasco’s coast. While the government professes to condemn Pemex’s actions, it continues to wave on the development of its newest refinery, a project which in the words of its own regulatory body for such matters, must not threaten the survival of protected mangroves. It is a perpetual paradox, and one that in all the confusion of the matter, may fall under the radar of the casual observer.

The evidence is clear to see. Roadways encroach farther and farther into the forest to allow vehicle access to the refinery, and existing clearings grow in size, incrementally removing swathes of the mangroves.

The campaign of deforestation in the area is, perhaps most importantly, being taken before the government’s official permit allows it to do so, and after the severe fine and reprimand it received from the environmental regulatory body. Pemex is already getting started, and perhaps the administration is afraid of intervention should any loose spanners end up in the proverbial works, threatening the longevity of the project.

López Obrador is ideologically a leader from a different age when it comes to the environment, focused almost exclusively on economic development with nary a glance or policy towards the current environmental crisis. As such, with Pemex in need of a boost, and AMLO’s campaign promise to save the country’s national oil company still echoing in the wind, all regulation is cosmetic in the face of the oil giant’s needs.

This reality is currently sitting at odds with a parallel pressure weighing on AMLO’s presidency, the importance of truly tackling Mexico’s carbon contribution as other leaders in the region continue to make similar commitments and Mexican cities show levels of pollution regularly exceeding target averages.

It is these two factors that continue to inform AMLO’s arguably erratic legislative activity: he supports Pemex’s building of an $8-billion refinery but insists the trucks that carry the oil must run on clean diesel. He offers a vast swathe of coastal land for said refinery but attempts to simultaneously protect the mangroves under threat, while ultimately rolling over after an apparent struggle, seemingly beaten back by the desperate needs of the economy.

Mexico’s environmental regulator is unlikely to pursue any meaningful action against those responsible for the destruction of the mangroves. Soon after the permit to develop the refinery was offered, the executive director of the ASEA, Luis Vera Morales, stepped down in protest, only to be replaced by Ángel Carrizales López, a diplomat who was once a close aide to AMLO.

This isn’t the first time that Carrizales López has been nominated by AMLO for a position in a regulatory body, but it is the first time he hasn’t been rejected by lawmakers, the position at the ASEA not requiring legislative approval. The fresh-faced leader has already committed to canceling the original $700,000 fine on the Pemex third party and is said to be hopeful of a relationship on good terms with the president, an attitude that could foster apathetic distraction from the conservation issues in question.

The president of the Mexican Center for Environmental Law, Gustavo Alanis-Ortega, has echoed an ongoing frustration leveled at the AMLO administration, saying that “If they are indeed breaking the law [at Dos Bocas], this shows that there is no real commitment to legality and the rule of law.”

This all mirrors a dynamic that has repeated itself since López Obrador took office: a prioritization of pragmatic action over environmental red tape. The Maya Train, a project that will run a network of trains throughout the southeast, was hurried, and it refused numerous times to await the analysis of an environmental impact report.

The same motivation at play in that ongoing saga is being revealed here as well, as the hope remains that legacy and demonstrable successes will eventually overshadow the methodological gray areas and drown out the nit-pickers with their clipboards.

Essentially, the green light the government has given Pemex is closer to amber. This is, at least, the message the government is trying to send, toeing both sides of the line until it can claim victory for an economic boost while simultaneously accepting its fair share of praise for taking on the environmental recklessness of the oil industry.

While it is true that the government has not provided explicit support for development of the mangrove zone, it has offered the industry an area rich in mangrove ecosystems. Is there really a difference? The government would say yes but in fact they’d rather not say anything at all.

Writer Jack Gooderidge is based in Campeche.