Amigos, this article sits somewhere between a book review and an invitation to a serious conversation about violence in Mexico. The facts you’ll read below come from a 12-year investigation by my friend, Carlos Pérez Ricart, which he distills with strenuous clarity into a little more than 200 pages.

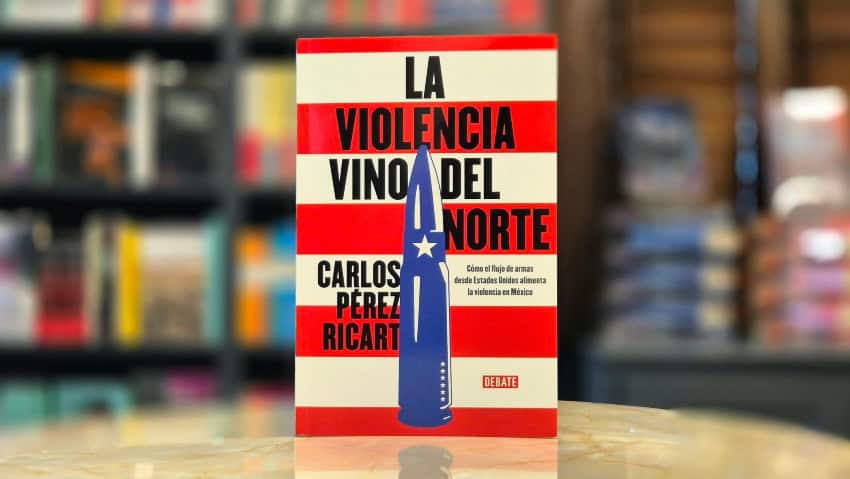

The title of his book is deliberately provocative: “La violencia vino del norte“ (“Violence Came from the North”). It is easy to misread it as a way of saying: the problem came from the United States, not from us. That is not what the book does. Pérez Ricart is not a pundit with a slogan; he is a researcher with a PhD in Political Science from the Free University of Berlin and academic experience at Oxford.

His work is the slow, unglamorous task of gathering, checking, and organizing data. In this latest book, he traces one decisive factor in a much larger story: how firearms — and the laws that regulate them in the United States — intersect with Mexico’s spiral of violence. Its scope is binational; its method, rigorously empirical.

If your Spanish allows, buy the book and read it. And in the hope that you will, I will try not to reveal more than necessary.

Mexico’s own house

Pérez Ricart starts where, for us, hurts the most: at home. Before talking about the U.S. gun market, he insists on a basic point: Mexico’s violence is not imported. It has deep domestic roots.

We know some of them by heart.

For instance, in February 2007, Mexico’s homicide rate was 5.8 per 100,000 inhabitants — among the lowest in the world. Then Felipe Calderón’s declaration of “war” on drug trafficking in the same year militarized public security and pushed criminal groups into open confrontation with the armed forces. There is, at the same time, persistent inequality, which leaves many young men facing a choice between badly paid, precarious legal work and a faster, riskier illegal economy. In those conditions, the “choice” is not really free. But the book asks us to look beyond the obvious.

One less discussed factor is local democratization. For decades, many municipalities were governed by the same party, the same network of power. Criminal organizations, within that stable setting, knew whom to approach and how to negotiate informal arrangements. When political competition arrived, those rules did not disappear; they broke apart. New mayors appeared, old allies left, and criminal groups that had operated in a predictable political environment suddenly faced uncertainty. Who decides now? Who can guarantee anything?

This is not an argument against democracy. It is a reminder that democratization, without strong institutions, can unsettle not only politics but also the informal order that had kept certain conflicts contained.

Another recurring idea in Mexico is that the state and organized crime are fused into a single corrupt structure. Pérez Ricart does not deny corruption. But his data complicates the picture. Between 1995 and 2014, 83% of attacks on public officials were directed at municipal authorities. Violence does not only touch the top; it reaches the level closest to citizens, often the most exposed and least protected.

Again, the first conclusion is uncomfortable and necessary: Mexico’s crisis is largely the result of its own history and decisions.

Only after establishing this does Pérez Ricart look north.

The largest gun market in the world

The United States is home to the largest and freest civilian gun market on the planet.

In 2022, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), more than 13 million firearms were manufactured in the U.S. Pérez Ricart distinguishes among types of weapons: not all guns are equally lethal. One model, however, stands out in his research: the AR15, a semi-automatic rifle that has become symbolic in the U.S. and is also one of the weapons most frequently trafficked into Mexico.

The problem is not only guns; it is also ammunition, which is produced at massive scale and is easy to buy. In practice, as Pérez Ricart notes, buying a box of bullets can be simpler than buying an antibiotic.

The density of guns in the U.S. is striking. By 2024, there were an estimated 114 firearms for every 100 residents — around 378 million guns in circulation.

The distribution network is equally impressive. By late 2022, there were 77,813 federal firearms licensees — legal points of sale. For comparison, there were about 15,873 Starbucks in the U.S., and 35,711 worldwide. In other words, gun sellers far outnumber coffee shops.

This is the environment the book describes: a vast legal industry with many layers, from major manufacturers and store chains to gun shows and private sales.

The law that changed the rules

Within this landscape, Pérez Ricart highlights one date: Oct. 26, 2005.

That day, President George W. Bush signed the Protection of Lawful Commerce in Arms Act (PLCAA). In simple terms, the law granted broad federal immunity to the gun industry against civil lawsuits for damages caused by the criminal misuse of their products.

For him, the law is also a turning point for Mexico. By limiting the industry’s legal exposure, it helped consolidate a system in which large-scale production and sale of weapons can continue while much of the human cost is paid abroad.

His thesis is not that PLCAA “created” Mexico’s violence. It is more precise: had that immunity not been granted in 2005, the U.S. firearms market might have developed under different pressures, and the intensity of the violence now affecting Mexico would likely be lower.

It is a counterfactual, not a mathematical proof. But it is grounded in data about what has happened since: the growth of sales, the spread of high-powered weapons and the constant appearance of U.S.-origin guns at Mexican crime scenes.

The southbound journey

On paper, Mexico has only two legal stores where civilians can buy firearms, both controlled by the Ministry of Defense. Compared to nearly 78,000 U.S. licensees, the contrast is extreme.

And yet Mexico is awash in guns.

How do they arrive? The mechanism Pérez Ricart describes is not spectacular. It is repetitive and discreet: “ant trafficking.”

A person with a clean record buys a gun legally in a U.S. store, often near the border. Sometimes this buyer is a “straw purchaser”: a relative, partner, or acquaintance who will not keep the gun. The firearm is registered in their name and then travels south, usually by land, hidden in a car, a van or a bus.

The key detail is in the inspections. Vehicles entering Mexico are not checked with the same rigor as those entering the U.S. Anyone who has crossed the border by road knows the difference.

Once in Mexico, weapons are redistributed to conflict zones using the same informal logistics networks that move people and goods every day.

One study cited in the book estimates that around 135,000 firearms crossed into Mexico in 2022. According to official U.S. data, roughly 70% of the traced guns seized by Mexican authorities had been purchased in legal, identifiable U.S. gun stores in border states.

For this flow to exist at the current scale, Pérez Ricart argues, there must be more than just cartels and vulnerable youth. There must also be, at a minimum, omission by some authorities. Sometimes, looking away is enough.

Lethality and responsibility

Would cartels exist in Mexico without guns from the United States? Yes. They are older than the current wave of firearms. Drugs, extortion, and smuggling did not begin with the AR-15.

What changes with easy access to powerful weapons is not the existence of crime, but its lethality. Its ability to confront the army on almost equal terms. Its capacity to control territory, intimidate entire communities, or kill a citizen, mayor or journalist.

Without high-powered guns, there would still be violence. But the number of deaths, the intensity of confrontations, and the capacity to challenge the state would probably be different, Perez Ricart explains.

But as he stresses, there is much Mexico can and must do. One obvious front is customs. If most weapons enter by land through legal crossings, then Mexico’s own border controls are a central part of any credible strategy. Technology, oversight and professionalization at customs matter. That idea — focusing on what Mexico can control — is one of the most pragmatic contributions of the book.

Opening, not closing, the debate

“La violencia vino del norte” shows that Mexico’s crisis is the product of internal factors we know well and external dynamics we often ignore. Both are real. Both matter.

Now that we have a clearer picture of how legal guns in the north become illegal weapons in the south, the question is no longer simply who is to blame. But who, on both sides of the border, is willing to act on that knowledge?

A final note: what you have just read is only the tip of the iceberg of Pérez Ricart’s work. Beyond the data, the book offers something harder to find in public debate: context and careful explanation of what those numbers tell us about the nature of violence on Mexican soil. It does not close the conversation. It gives us better tools to begin it in places like Mexico News Daily, with binational communities.

Maria Meléndez writes for Mexico News Daily in Mexico City.