Just at the end of last year, in November 2025, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins led the largest public-private agricultural delegation the United States has ever sent to Mexico.

Hundreds of American business leaders and government officials traveled to Mexico City to work through challenges and — more importantly — to strengthen and expand agricultural ties between both countries.

Then, just last week, Senator Roger Marshall from Kansas headed another U.S. delegation to Mexico, again focused squarely on agriculture.

And, almost perfectly timed, we’re now just a couple of weeks away from the Super Bowl, an event for which Mexico is expected to export a record-breaking volume of avocados to the United States: more than 280 million pounds (around 127,000 tonnes). How and why the most iconic American sporting event ended up being inseparable from one of the most Mexican dishes — guacamole — is still a mystery to me. If anyone knows the origin story, please enlighten me.

Jokes aside, when cabinet secretaries, senators and avocados are all moving north and south at the same time, it’s usually a sign that something important is happening. And yes, something has been happening for a while now. I’ll briefly share four reasons why Mexico is extraordinarily relevant to the U.S. agricultural industry.

Agricultural diplomacy in Mexico, North American edition, with yours truly. Left: Secretaries Julio Berdegué 🇲🇽 and Brooke Rollins 🇺🇸. Right: Sen. Roger Marshall and the AMCHAM crew.

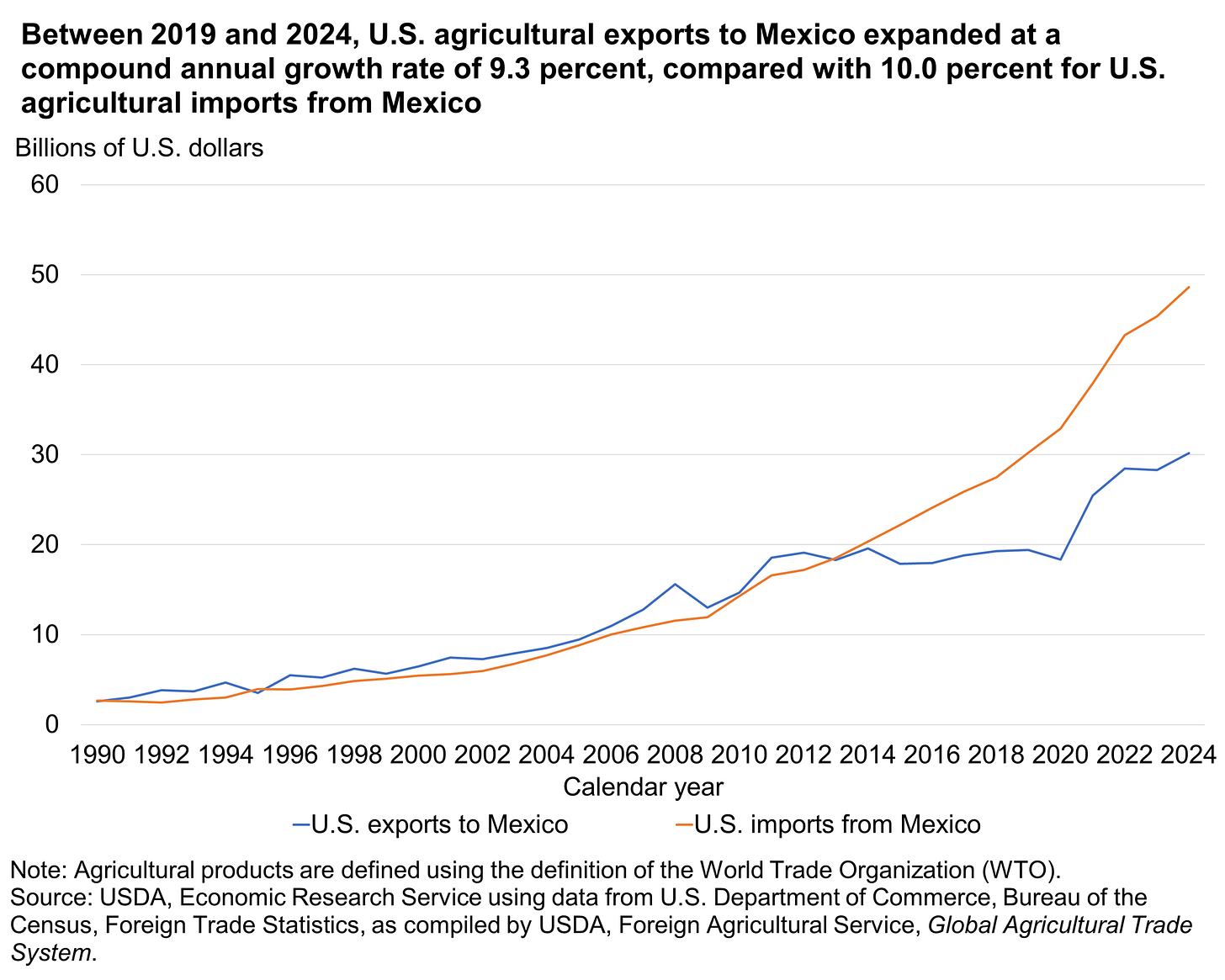

First and foremost is how much Mexico buys from American farmers. Mexico is the number one destination for U.S. agricultural exports, reaching $30.3 billion in 2024, ahead of both China and Canada. Agricultural trade with Mexico supports more than 325,000 U.S. jobs, from farm fields to processing plants, rail lines and ports, making Mexico one of the most essential pillars of rural employment in America.

Second, and contrary to what many people think, the agricultural sectors of Mexico and the United States are complementary, not competitive. The two countries do not grow the same things, at the same time, or in the same way.

Mexico supplies fruits, vegetables and beer at scale — often when those products are out of season in the U.S. Meanwhile, the United States supplies Mexico with grains, feed, meat, dairy and staples that Mexico structurally imports. Mexico depends on imports for roughly 50% of its corn and about 95% of its soybeans, with the U.S. holding a dominant market share. David Ricardo would be proud: this is textbook comparative advantage in action, where each country specializes where it is strongest, creating regional food security rather than zero-sum competition.

Third, and closely linked to that point, is the stabilizing effect on prices and consumption for everyday Americans. Nearly half of U.S. agricultural imports from Mexico are products that are out of season or not widely grown domestically. Mexico supplies over 50% of U.S. fresh fruit imports and nearly 70% of fresh vegetable imports. This keeps grocery shelves stocked year-round and dampens price volatility, especially during weather shocks.

In agriculture, stability is value. Integrated trade acts as a shock absorber against climate volatility and seasonal scarcity. I won’t dive into climate change here, but droughts, hurricanes and fires speak for themselves, and coordination in this sector is not optional if we want to avoid serious trouble.

Lastly, to keep this short and sweet, is looking ahead. Mexico’s demographics, poverty reduction and (hopefully) sustained economic growth point to a rising market for U.S. farmers and producers. Over the last six years, Mexico has lifted around 13 million people out of poverty, expanding its middle class and purchasing power. Rising incomes drive dietary upgrading: more protein, dairy, processed foods and higher-quality products. At the same time, Mexico’s younger population means demand growth is demographic, not cyclical (don’t forget to read my text on demographics — it’s a good one). Why does this matter? Because a growing, wealthier Mexico means more consistent, long-term demand for U.S. agricultural exports — especially grains, feed, meat and dairy.

Put together, this is a pretty solid set of arguments: Mexico as the number one buyer of U.S. agricultural products; a deeply complementary production system; a stabilizing force for prices and consumption; and clear upside potential in the years ahead. Make no mistake: Mexico is fundamental for U.S. farmers and producers, and therefore for the broader American economy.

That’s all for this week. I appreciate you reading and sharing this piece. Substack keeps congratulating me on the growing number of readers, and that makes my Sunday writing even more worthwhile.

If this is the first time you’ve read me here, this text is part of a series titled “Could Mexico Make America Great Again?” You can find all the texts in my profile or following these links: i) Intro; ii) China; iii) Demographics; iv) Co-production; v) Artificial intelligence; vi) Energy; vii) Autos.

Cheers — and see you next week!

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.