A few years ago, I spent my life savings, earned a couple of scholarships, and took on a substantial amount of debt (still paying it, by the way) to engage in a very specific “trade relationship” with Georgetown University and the United States.

Aside from a few hundred dollars spent on cool sweatshirts, T-shirts, caps and mugs (goods), several thousand dollars went into a particular service: education. With that, for a couple of years, I contributed — very personally — to one sector of the bilateral relationship where the United States consistently runs a surplus: services.

Keeping this text short will be hard, but let’s start by clarifying what services trade actually means. We usually picture trade as cars, TVs, clothes, berries or avocados crossing the border. But what about all the things that don’t come in boxes?

Teenagers flying to Cancún for spring break. Well-dressed bankers in New York managing Mexican investments. Tech folks selling software, cloud and IT services. Consultants, insurers, logistics providers. And yes — students paying tuition in Washington, D.C.

All of that (and much more) can be described as services trade between Mexico and the United States.

So how big, and how relevant, is it?

Mexico may not be the United States’ top services partner, but it is firmly within the top five. In 2024, total U.S.-Mexico services trade reached roughly $96 billion. By the end of Q3 2025, it was already around $70 billion, about 15% higher than the same period in 2024. In that same year, the U.S. ran a $5.3 billion surplus in services with Mexico; by Q3 2025, that surplus had already grown to about $6.3 billion.

Even more interesting is the trend. Between 2020 and 2024, U.S. services exports to Mexico more than doubled (+114%), while services imports from Mexico grew even faster (+152%). That reflects post-COVID normalization — yes — but also something deeper: more travel, more transport, more digital services and far more cross-border business integration.

With that in mind, let me highlight three big buckets driving this relationship.

First: travel and tourism.

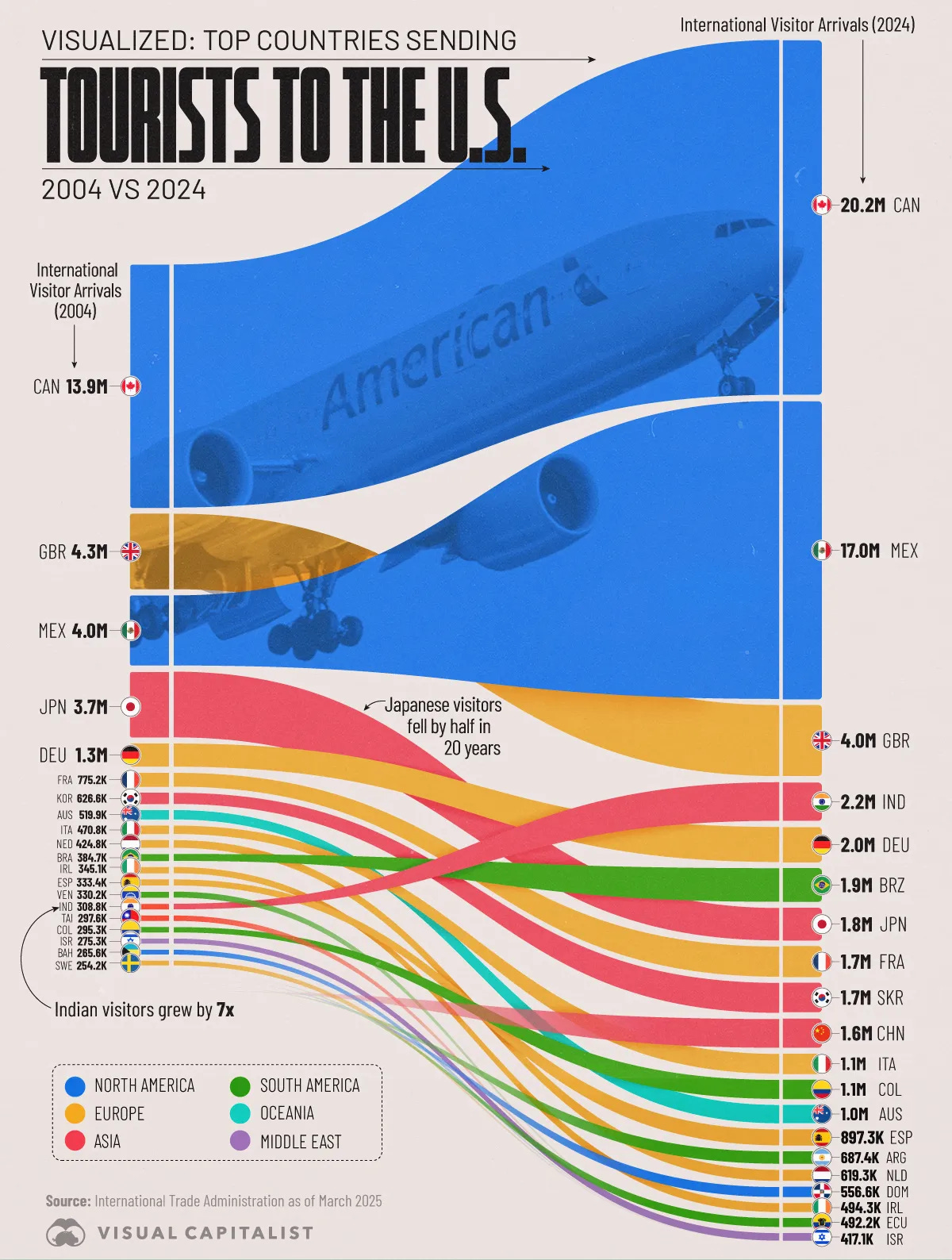

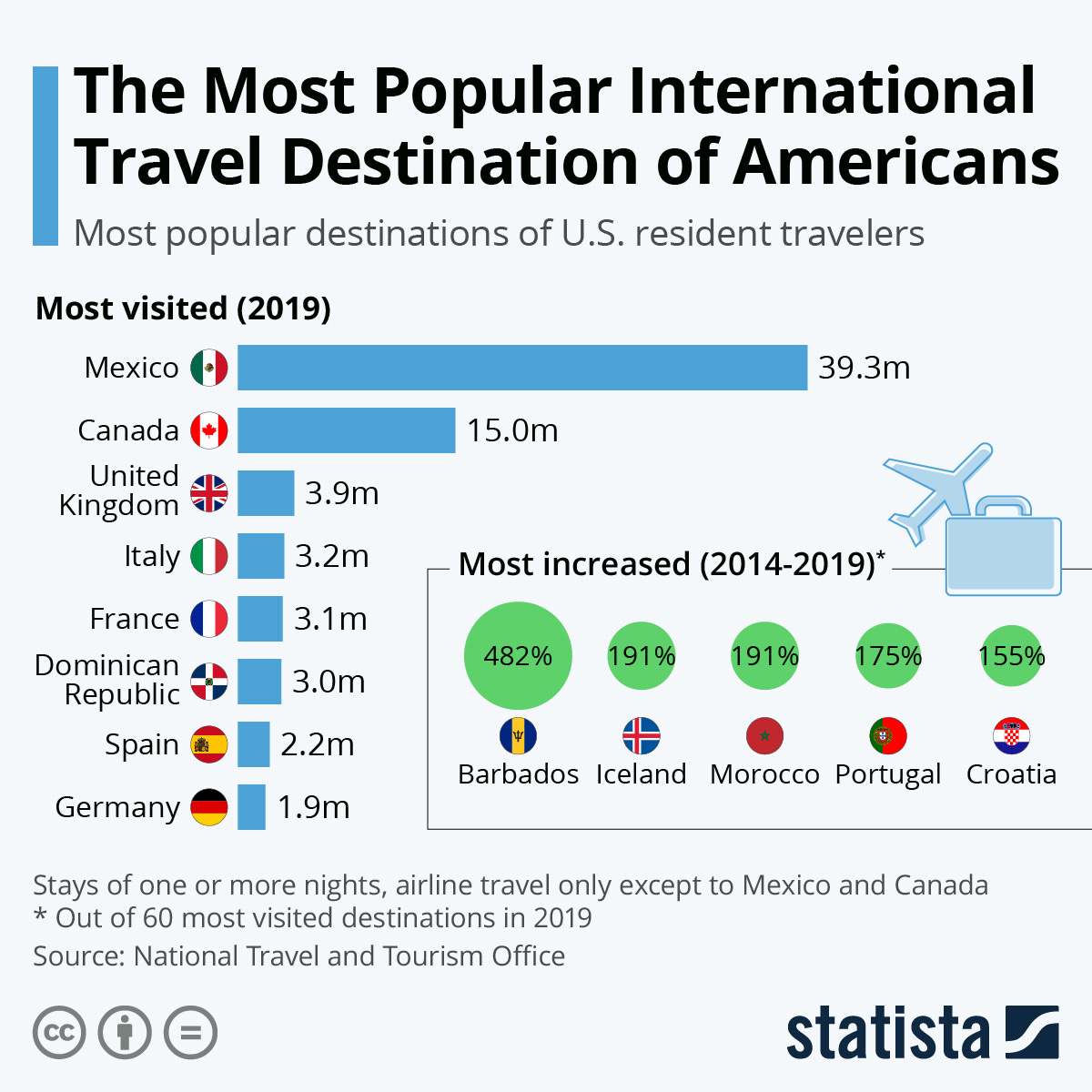

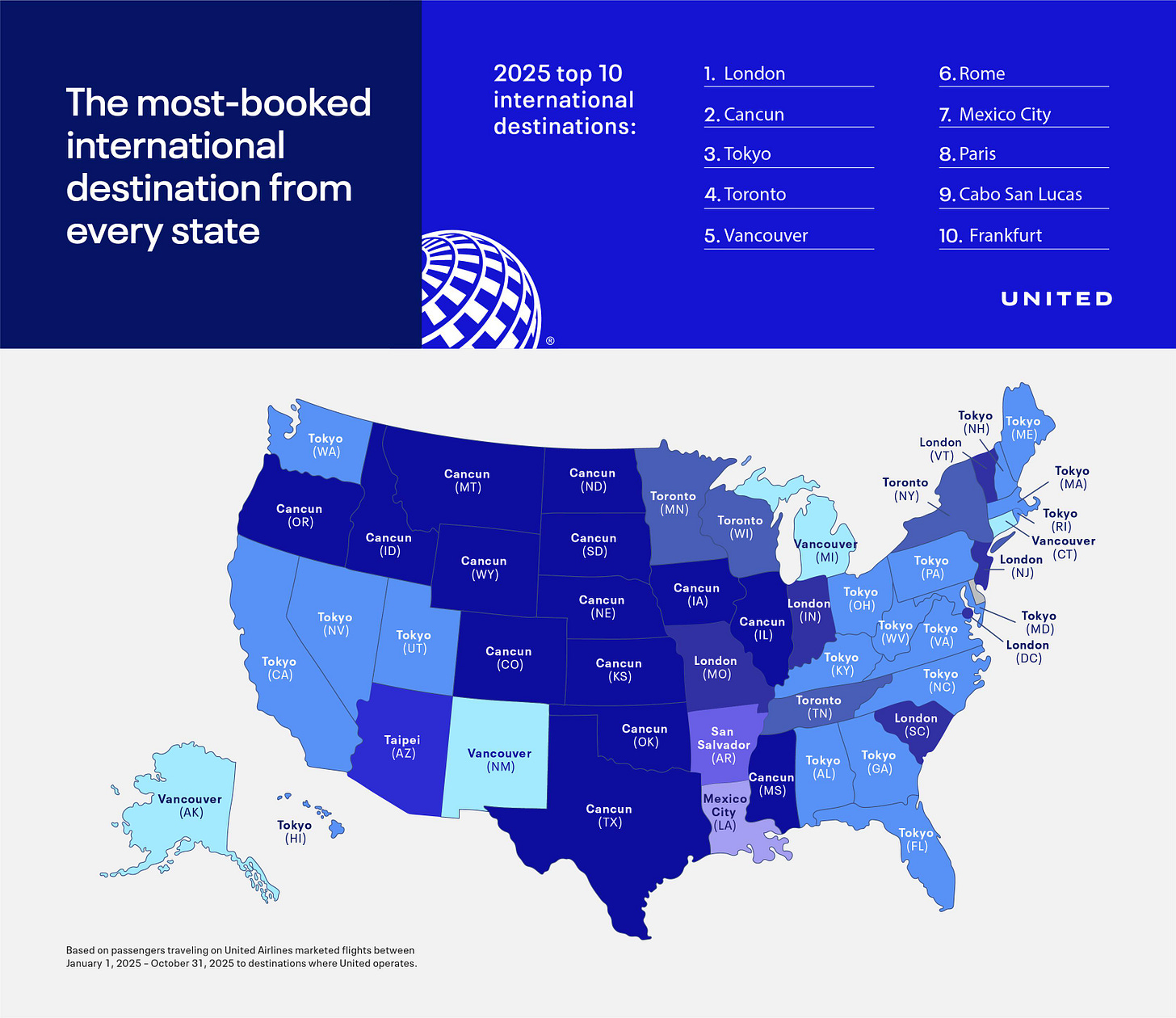

Tourists from Mexico to the United States have more than quadrupled in the past two decades. On the other hand, Mexico is the United States’ top international flight destination. Roughly 45 million passengers fly between the two countries every year. That’s about 1.6x Canada, the second-largest destination, and roughly five times Japan, which ranks fifth. While tourism often looks like a “deficit” on paper, it’s also a massive welfare gain for Americans: world-class beaches in Cancún, Cabo, Vallarta and Tulum; food, arts and culture in Mexico City and Oaxaca; and historic towns like San Miguel de Allende, Querétaro and Guanajuato.

Services trade isn’t just about balances. It’s about value, quality of life and choice. Here they come, a good set of infographics, enjoy:

Second: logistics, transportation and business services — the packaging layer of goods trade.

As trade of cars, electronics and food grows, so does freight transport, warehousing, customs services, express delivery, accounting and professional support. These services grow alongside goods trade and rely heavily on local SMEs, especially at the border and in destination cities. More goods integration automatically means more services integration.

Third, and the fastest growing, are digital and knowledge-based services: finance and insurance, software, cloud computing, IT services, data processing, telecom and professional services. I’ll pause here, because this is what will push North America into its next phase of global competitiveness. If you haven’t read my text on AI yet, this is your cue (click here, then come back).

Zooming out, history tells us something simple about a country’s development path. Economies tend to evolve from agriculture to manufacturing to services. The United States is already the world’s services powerhouse: apps, finance, education, AI, intellectual property, even space. Moving backward from that would be just that: a step backward. The real opportunity is anchoring U.S. services leadership to a still-powerful manufacturing base, while pulling Mexico along the value chain, from low-skill manufacturing toward higher-skill, higher-value services. That’s not a threat; it’s how regions win.

As we approach the USMCA review, the goal should be clear: a legal framework that reduces friction, aligns regulations and accelerates growth rather than slowing it down. Services trade with Mexico creates U.S. jobs, delivers a consistent surplus, injects huge amounts of money into the U.S. economy, and strengthens the broader North American platform that enables both countries to compete globally.

With that being said, and thanks for reading this far, you can now go back to reading other things on Substack, binge the latest Netflix series, text your friends on WhatsApp, order something from Amazon, or just keep scrolling through apps powered by cloud services and American satellites.

Congratulations! You just participated in U.S.-Mexico services trade. Cheers!

Catch up on parts 1-8 of Could Mexico make America great again? here:

- Part 1: An introduction

- Part 2: A primer on China

- Part 3: Zeroing in on the demographics

- Part 4: About that trade deficit

- Part 5: How the AI race changes the game

- Part 6: The energy equation

- Part 7: Why ‘value added’ matters more than gross trade

- Part 8: The bilateral agriculture relationship

Pedro Casas Alatriste is the Executive Vice President and CEO of the American Chamber of Commerce of Mexico (AmCham). Previously, he has been the Director of Research and Public Policy at the US-Mexico Foundation in Washington, D.C. and the Coordinator of International Affairs at the Business Coordinating Council (CCE). He has also served as a consultant to the Inter-American Development Bank.