More Americans than ever are choosing to live in Mexico – and many have decided to settle in the capital rather than coastal resort cities that are popular with tourists on short breaks.

Formal immigration to Mexico from the United States is at a record high, federal government data shows, while many more Americans are living and working here while on tourist visas.

Data published in an Interior Ministry migration report shows that 8,412 U.S. citizens were issued temporary resident visas in the first nine months of the year, an 85% increase compared to the same period of 2019 – when the coronavirus pandemic hadn’t yet had an impact on people’s life and work choices and options. The figure is the highest since comparable data became available in 2010, the news agency Bloomberg reported.

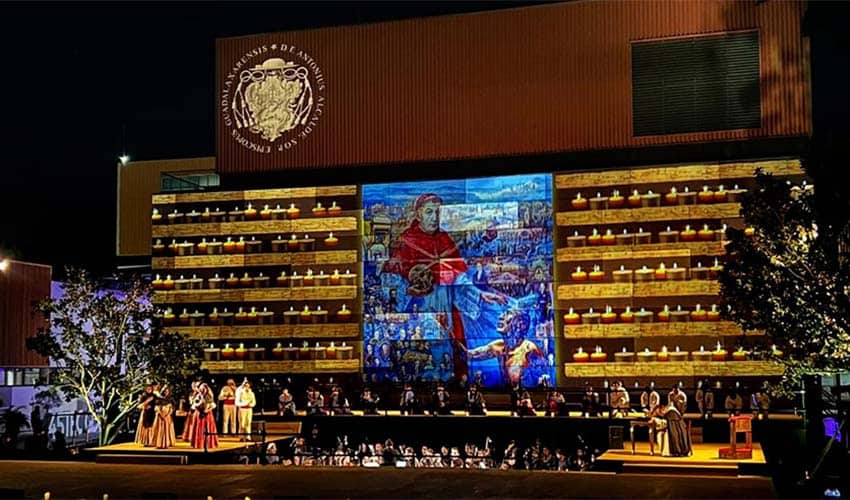

Data shows that 1,619 of the Americans granted temporary residency this year – 19% of the total – live in Mexico City, while 1,515 live in Jalisco, mainly in Puerto Vallarta, Guadalajara and Chapala.

The next most popular states for new temporary residents from the U.S. are Quintana Roo, which includes Cancún, Playa del Carmen and Tulum; Baja California Sur, which includes Los Cabos and La Paz; Yucatán, which includes Mérida and the port city of Progreso; and Guanajuato, which includes expat hotspot San Miguel de Allende and Guanajuato city.

The number of U.S. citizens who were granted permanent residency in the first nine months of 2022 also increased significantly, rising 48% from 2019 levels to 5,418. There are a range of ways foreigners can qualify for residency in Mexico, including by meeting income requirements, having an employer who sponsors their visa and having family ties.

The aforementioned residency figures don’t take into account the large number of Americans who entered the country as tourists but are living here for all intents and purposes. Such people include a growing number of digital nomads – many of whom were able to settle here due to new remote work policies introduced by their employers during the pandemic – as well as older, retired Americans, some of whom have been spending part of their time in Mexico for years.

Mexico has typically allowed tourists to stay for six months, although that period of time isn’t guaranteed. Many Americans return briefly to their home country before re-entering Mexico on a new tourist visa and resuming their lives here.

For many digital nomads, the location of choice is Mexico City, especially trendy inner city neighborhoods such as Roma and Condesa, while Oaxaca city is another destination that is popular with Americans and foreigners in general.

Some Mexicans have expressed concerns about the influx of digital nomads to certain parts of the capital during the pandemic, asserting that their presence has pushed up rents – a claim backed up by data compiled by the real estate website propiedades.com – and driven locals out of desirable neighborhoods.

But those concerns didn’t stop the city government from entering into a partnership with Airbnb that aims to attract even more nómadas digitales to the capital. One response to that move was a social media post that advised digital nomads that “Mexico is not cheap when you make pesos.”

“Your Instagram-worthy lifestyle is ruining your home,” added the IG post, which attracted over 3,500 likes. “Stop colonizing Mexico City.”

In defiance of such opinions, Mexico City Mayor Claudia Sheinbaum said her government wants to increase promotion of the capital to digital nomads. At a press conference last week to announce the agreement struck with Airbnb, the mayor asserted that the ongoing arrival of the mainly young remote workers – perhaps in even greater numbers in the near future – will benefit parts of the city beyond tourism hubs, one of which is described by some people as the “Roma-Condesa bubble.”

Her remarks did little to mollify tenants’ rights groups, which said that the partnership with Airbnb was part of the “aggressive touristification” of Mexico City. In a statement, they demanded greater regulation of the accommodation booking platform.

Opposition from locals appears unlikely to deter foreigners from coming to the nation’s capital – which became something of an international “it city” in the last five years or so – and to other parts of the country.

In addition to Americans, foreigners from many other countries have flocked to Mexico in recent years, attracted by the country’s openness and lack of restrictions during the first year of the pandemic, as well as traditional draws, including beaches, archaeological sites, tasty food and beverages and the wide range of cultural experiences on offer.

So it’s not surprising that an increasing number of Americans – and other foreigners – don’t want to go home. Government data also shows that the number of Canadians granted temporary residency in the first nine months of the year went up to 2,042, an increase of 137% compared to 2019.

More than 1,000 citizens of many other countries received temporary residency permits between January and September. Those counties include Spain, France, Germany, China, India, Japan and numerous Latin American nations, among which are Colombia, Argentina, Brazil and Cuba.

But none of those countries can compete with the United States in terms of the total number of citizens residing in Mexico. The U.S. Department of State said last month that “an estimated 1.6 million U.S. citizens live in Mexico,” while data from Mexico’s 2020 census put the figure at a more modest total of just under 800,000.

Among the U.S. citizens living here are a growing number of families with children, attracted in part by Mexico’s family oriented-culture. Data from Mexico’s 2020 census shows there are over 470,000 U.S.-born kids aged five to 19, although many of those likely belong to Mexican families.

In addition to being a popular place to settle, Mexico is also the top foreign destination for U.S. travelers, according to the State Department, while data from the Center of Research and Tourism Competitiveness at Anáhuac University in Mexico City shows that more than 10 million Americans flew into Mexico in the nine months to the end of September, injecting billions of dollars into the Mexican economy.

An increasing number of them didn’t just come for a short break on the beach in Cancún, Puerto Vallarta, Los Cabos or Zihuatanejo. For better or worse, many foreigners – including large numbers of Americans – are here to stay.

With reports from Bloomberg