Fiery narco-blockades in Baja California and Guanajuato last Friday capped a violent week in Mexico, during which criminal groups ran riot in four states.

The wave of violence began in Jalisco and Guanajuato last Tuesday when the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) responded to the arrest of one of its leaders by setting vehicles and businesses on fire. On Thursday, a brawl between members of rival criminal gangs imprisoned in a Ciudad Juárez jail and a subsequent wave of attacks in the northern border city claimed the lives of at least 10 people, including innocent civilians.

The violence spread to several Baja California cities on Friday – including Tijuana and state capital Mexicali – and returned to Guanajuato, Mexico’s most violent state.

According to a Reforma newspaper report, armed men seized and set alight at least 19 vehicles in Tecate, Tijuana, Playas de Rosarito, Mexicali and Ensenada. Public transit buses and trucks were among the vehicles set ablaze, reportedly by CJNG-affiliated criminals. Ten vehicles were torched in Tijuana to block roads in the northern border city.

I left Baja Beach Fest about an hour ago, there was no signal. Festival goers probably don’t know what’s happening. There’s no way everyone at the festival is staying in Rosarito. Taxis aren’t going into Tijuana. The festival hasn’t been canceled. This is going to be chaos.

— Alexis Hodoyán👷🏻♀️ (@hoe_doyan) August 13, 2022

The United States Consulate General in Tijuana issued a security alert amid the chaos and instructed U.S. government employees to shelter in place, an order that wasn’t withdrawn until Sunday.

Baja California Governor Marina del Pilar condemned the violence and reported that arrests had been made but didn’t specify how many. Federal officials said later that 17 suspects were detained, including seven people in Tijuana and four in each of Mexicali and Rosarito.

In a Twitter post on Saturday, Del Pilar assured that her government was working to protect residents and attend to “each of the violent events” that occurred in Baja California, where one person was reportedly injured but there were no deaths.

Some 300 soldiers and 50 additional National Guard members were dispatched to Tijuana on Saturday to bolster public security efforts in the state, where thousands of guardsmen are permanently based.

Three days after presumed CJNG members murdered at least two people and torched scores of businesses and vehicles in Guanajuato, the Bajío region state saw another outbreak of violence on Friday. Cartel henchmen once again set vehicles alight to create narco-blockades, this time after a confrontation with security forces on the Celaya-Juventino Rosas highway.

After the clash, state police pursued a pickup truck but their chase was hindered by spike strips and blockades that were created by setting two vehicles on fire near the community of La Veguita, according to a Milenio newspaper report.

On social media, messages attributed to the CJNG warned people to stay at home over the weekend in both Baja California and Guanajuato. The Los Angeles Times reported Sunday that Avenida Revolución – the main entertainment strip in Tijuana – had become a virtual ghost town.

However, in a Twitter post on Sunday, Tijuana Mayor Montserrat Caballero said the city wouldn’t stop or be divided by Friday’s violence. She also sent a message to criminal organizations, telling “thugs” to settle their scores “outside our city.”

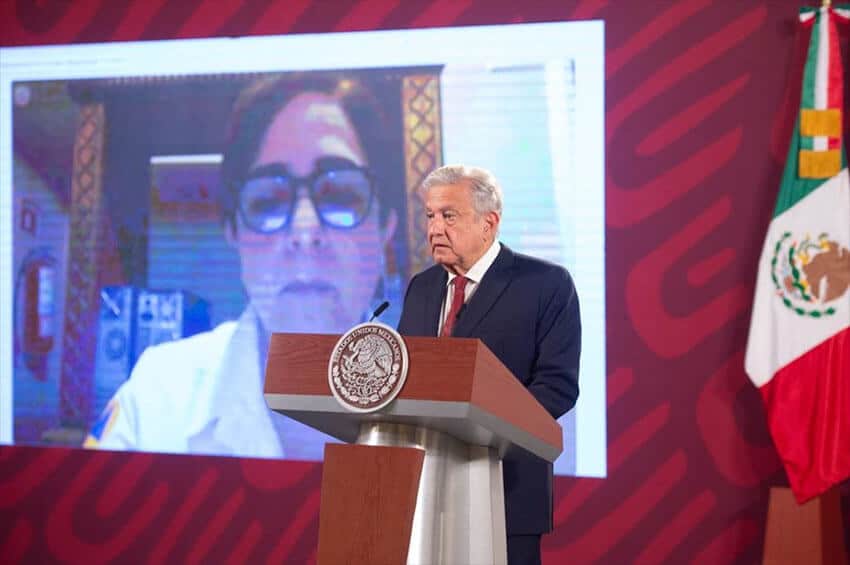

WATCH: President Andrés Manuel of Mexico (@lopezobrador_) said that the acts of violence recorded in Baja California were “more propaganda” and that, as a result, “there are people who are thinking about political issues,” but they should not be given too much weight. 🧵👇 pic.twitter.com/tCdpvB1vu7

— BNN Newsroom (@BNNBreaking) August 15, 2022

“We don’t want you here, don’t interfere with those of us who work every day to build a better future and a Tijuana for everyone,” Caballero wrote.

For his part, President López Obrador on Monday advised citizens to remain calm despite the violent events of last week.

“To the people of Mexico, I say be calm. There is governability, there is stability,” he said at his regular news conference.

The president claimed that the government’s political adversaries – the “conservatives” – were “exaggerating things” to make the security situation appear worse than it really is. López Obrador said that there were only 196 homicides across Mexico in the three-day period between Friday and Sunday, not 260 as some media outlets reported.

With reports from Reforma, Milenio and The Los Angeles Times