I just took a trip!

It was just a short trip to Mexico City to get my daughter’s passport renewed but, oh, what a breath of fresh air to get out of one’s own city once in a while. And now, after two and a half long years, we are finally going to be able to travel home to Texas for a couple weeks this summer.

We made sure to stay close to the U.S. Embassy so that we could be there on time for our 8 a.m. appointment. (By the way — for those of you with appointments soon — you do need an appointment, but once you get there you have to line up outside and it’s first come first serve, so go early!) in the beautiful Roma neighborhood, which to me is an urban utopia.

The streets and sidewalks were wide and well-kept, the buildings were beautiful, and there were trees and plants everywhere. Properties were, for the most part, well taken care of, and crosswalk lights clearly indicated where to go.

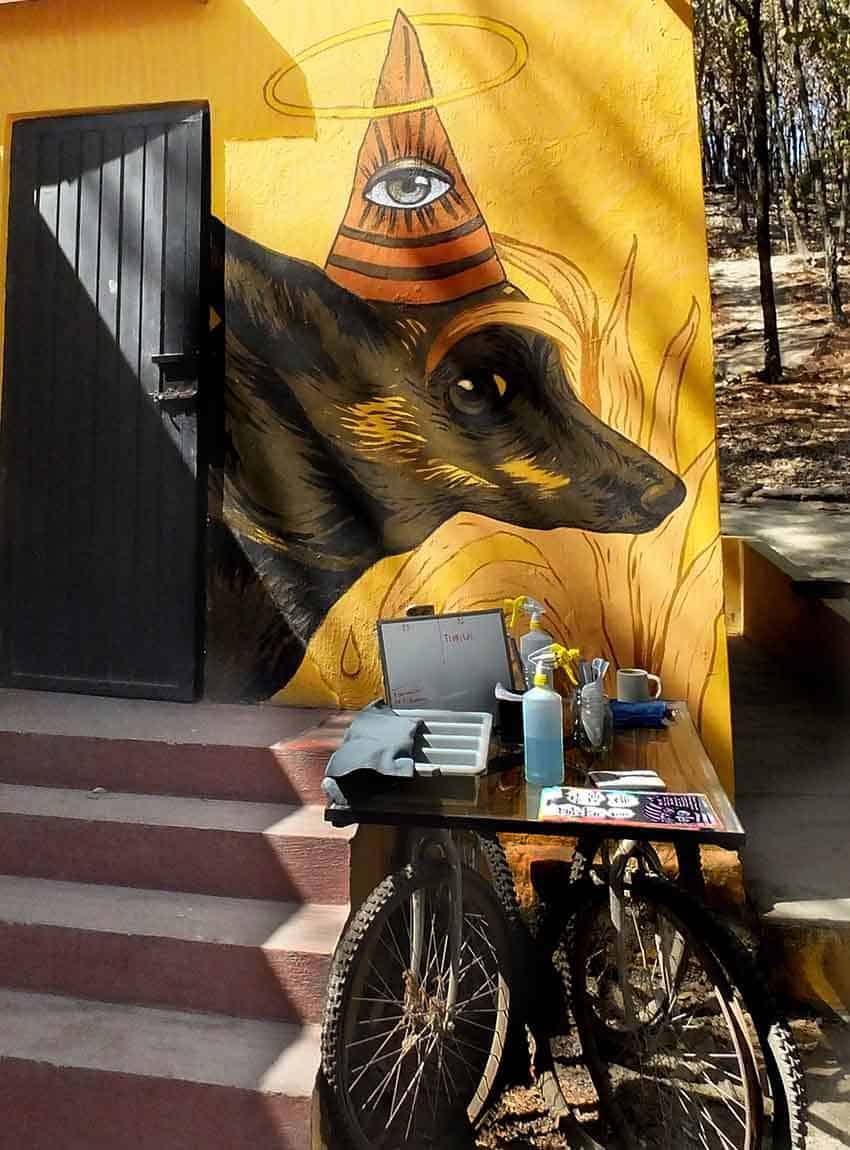

To my delight, there were several breweries in the area (I had a delicious blonde ale with avocado leaf and a stout that was essentially layered chocolate cake, if you must know), as well as coffee shops and convenience stores, many with cute little patio coverings for sidewalk lounging and dining. Murals seemed to be everywhere.

As we hung out with my daughter at one of the giant public playgrounds and listened to all the different languages being spoken, I found myself thinking what I always think when I’m in this kind of neighborhood: why can’t all places be this nice?

I know the litany of obvious answers. Mostly it’s money and investment.

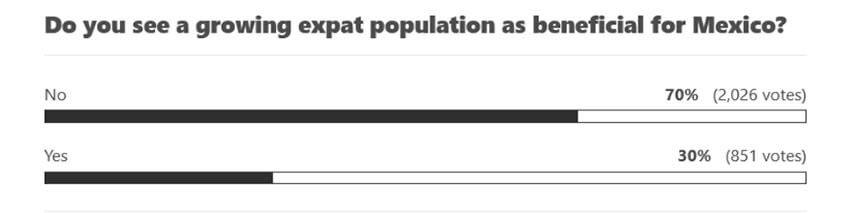

But bringing money and investment to a place doesn’t necessarily fix any problems without creating new ones, and that’s what makes me despair. What I want to know is this: is there a difference between gentrification and the real, tangible improvement of a place? Is it possible to make a place beautiful, accessible and safe without making it economically inaccessible to those who already live there?

Surely there is a way, though it’s not something I’ve figured out yet. And you all know (well, you do if you’ve been reading my column for a while) that I deeply value good design and intentional physical beauty in the communities that we humans create for ourselves.

In fact, I’d say that one of my most sacred beliefs is that everyone deserves to have physical surroundings that are safe, functional and pleasing.

Safe and functional seem straightforward, but even that can be tricky. Safe for whom? People? Cars? Bikes? Animals? Functional for which members of the community? You simply can’t just plop a bunch of “improvements” in the middle of nowhere without asking people what they actually need and want. And even when you do, not everyone everywhere is going to be happy with the changes.

“Pleasing” is even more difficult. The jury’s always out on that, and I can certainly accept that not everyone out there possesses my own hippie-bougie aesthetic ideals.

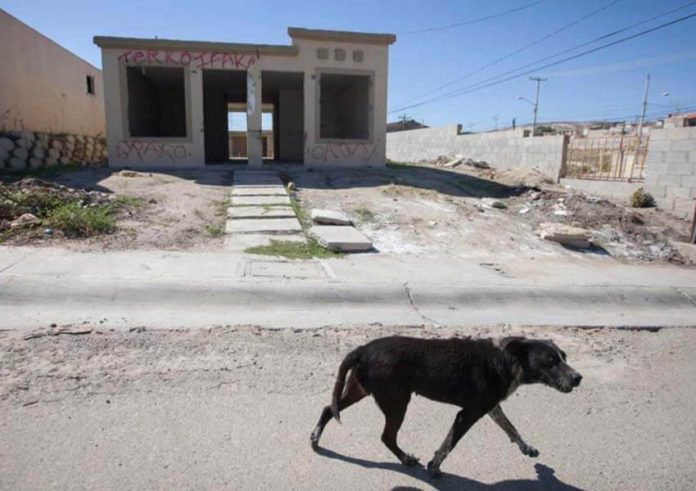

So it’s not that I think that all of urban Mexico should look exactly like the upscale Roma and Condesa neighborhoods. I just think that everyone in urban Mexico deserves that level of care put into the designs of their communities.

Mexico City – at least the places I passed on the bus – does seem to be getting the hang of it fairly well. Murals were everywhere in the city, as were playgrounds with exercise equipment and tracks wrapping around them. Public transportation had expanded since the last time I went.

So, surely there are a few things that we can agree on: walkable sidewalks, drivable streets, bike lanes for people who ride bikes.

Plants and paint, as well, go a very long way, and they’re relatively cheap.

But how to prevent gentrification?

I think the key is community involvement in revitalizing what’s there: letting those who actually live in those spaces decide how those resources will be displayed in the neighborhoods where they live.

Having them participate in what’s produced would mean some important steps in ownership and pride, similar to what the Mar de Jade Hotel has provided for young people where it’s building.

Can this get everyone their own versions of Roma … ones that they actually get to stay in?

Time (and politics) will tell. But I stand firm in one basic belief: everyone deserves to live in a place like that.

Sarah DeVries is a writer and translator based in Xalapa, Veracruz. She can be reached through her website, sdevrieswritingandtranslating.com and her Patreon page.