A large migrant caravan is heading north after leaving Tapachula, Chiapas, where National Guard troops in riot gear were unable to stop it despite a blockade across the highway on Saturday.

As many as 2,000 migrants set off from Bicentenario Park in Tapachula at around 7:00 a.m. and marched north up the main highway. The National Guard attempted to block their path near the town of Viva México but the front of the caravan charged the police line and, amid chaotic scenes, crowds of people ran past the authorities, who were unable to deter the surge.

By Sunday night the caravan had arrived in Huehuetán, having met no serious attempt to stop it, though immigration officials, National Guard officers, the army and the navy were seen traveling on the highway.

The majority of the migrants are from Central America. Pregnant women, seniors, one person in a wheelchair and many families pushing strollers with young children are among the convoy. Many said they had asylum claims or that the living conditions in their countries were intolerable. The caravan’s leader, Mexican-U.S. activist Irineo Mújica of Pueblos Sin Fronteras, or Peoples Without Borders, said the goal of the march was to travel to Mexico City, but many migrants said they were committed to reaching the United States.

The convoy’s first major milestone is Huixtla, about 40 kilometers north of Tapachula. Organizers said the success of the march could depend on whether officials try to obstruct the caravan near there. From there, the group plans to move toward the state capital Tuxla Gutiérrez, about 330 kilometers farther north, from which Mexico City is another 840 kilometers.

Here is the moment earlier today the caravan, under the sign of the cross, broke through the lines of the Guardia Nacional. pic.twitter.com/Dy217NZ3MF

— Jonathan L. Krohn (@JonathanLKrohn) October 23, 2021

Most of the migrants are poorly prepared, many wearing unsuitable shoes and walking in extremely hot conditions. They sleep in the warm open air without tents or cover. There is no system for the migrants to be fed and one woman was treated for exhaustion Sunday morning.

The convoy’s leaders are keeping one lane of the three-lane highway open to passing traffic. However, sometimes the migrants stray into the third lane causing traffic to build up behind.

Representatives from the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH) said the caravan was smaller than previous ones, but recognized a considerable presence of pregnant women and children.

Guatemalan, Salvadoran, Honduran, Nicaraguan and Venezuelan are the principal nationalities, but Cubans, Colombians, Ghanaians, Nigerians, a Chinese family, and at least one Panamanian are also part of the convoy.

Haitians, thousands of whom are in Tapachula, have not joined the caravan in large numbers.

The group slept in the small town of Álvaro Obregón Saturday night. The atmosphere was peaceful and local merchants appeared pleased with the sudden increase in business. They spent Sunday night in similar conditions in Estación de Huehuetán, and were well received by locals.

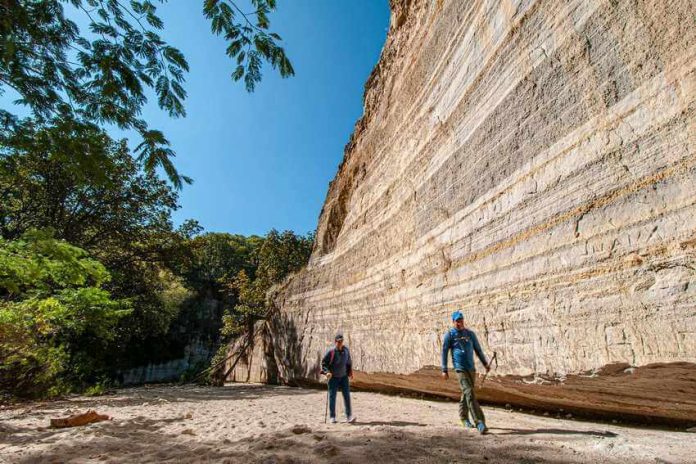

Faith plays an important role in caravans, also known as the “Migrant’s Way of the Cross,” a term that relates to the Catholic pilgrimage tradition. The caravan is spearheaded by a large wooden cross, which is normally carried by Salvadoran Víctor Manolo Contreras. He blamed corrupt Salvadoran governments for mass migration.

“The rich and the politicians are always looking to benefit themselves … we came from 30 years of disgraceful governments. They robbed with their hands full and finished the country,” he said.

Caravan leader Mújica is a devout Catholic and another leader, Mexican Luis García Villagrán of the Center for Human Dignity, is an evangelical Christian.

García said the spirit of the caravan would help it overcome obstructions in a speech on Saturday night. “There are more than 1,000 men, young men, we are more than them … They [security forces] try to look the part with a uniform and a helmet. But we are guided by our hearts, we are guided by necessity, we are here to survive,” he said.

Representatives from CNDH and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) are following the caravan in an observational capacity. Officials from the National Immigration Institute (INM) are providing medical assistance. Mexican human rights NGOs and Save the Children are also present.

Tapachula is the modern Casablanca: a city flooded with migrants, desperately awaiting their papers, which may never arrive. Their legal status is increasingly clouded: they have been banned from leaving Tapachula while they await the outcomes of their applications to the government refugee organization Comar and the INM. However, both agencies have buckled under the pressure of migrant influxes leaving undocumented migrants waiting for responses to applications without any reliable time frame.

The INM has not responded to applications for residence for more than two years in some cases, the newspaper El Orbe reported.

Many of the migrants who enter Mexico illegally quickly become well acquainted with the INM, which sends them to the prison-like migrant detention centers that it runs. Their imprisonment is called “rescue” by federal officials.

Mexico News Daily