The prickly pear cactus is an integral part of Mexico’s long history; it’s part of the Mexican flag, complete with tunas, the red fruit of said cactus.

The design comes from an Aztec legend about the founding of their capital city. Directed by the god Huitzilopochtli, the ancient Aztecs searched for a site where an eagle sitting on a prickly pear cactus growing on a rock in a lake was eating a snake.

It took 200 years of wandering, so goes the story, but they finally came upon that exact scenario, and the city of Tenochtitlán — what became Mexico City — was founded.

The paddles (nopales) of the cactus are a part of traditional Mexican cuisine, used in stews, tacos and many other foods; the fruit is the tuna, known in English as prickly pear.

The cactus plants grow to be quite large and formidable and are used for fencing to this day.

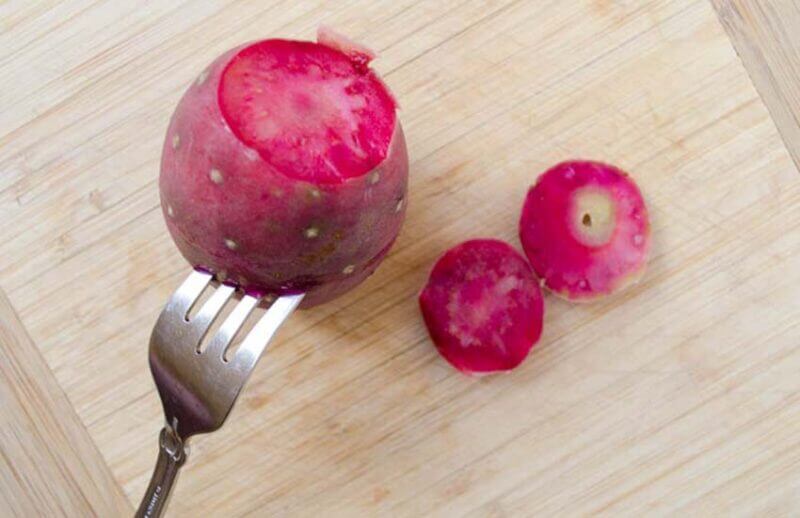

It makes sense that tunas are also called prickly pears, as the skin is covered with two kinds of spines: small clusters of hard, whitish spines grow all over the small fruits and are visible to the eye, but there are also soft, hairy filaments on the fruits.

Extreme caution — and gloves — are advised when handling tunas.

Tunas have a sweet, melon-like flavor, which some compare to bubblegum or watermelon. They don’t taste anything like they look, and inside the rough, spine-covered skin is a delectable and very edible fruit.

They come in a wide range of colors — from yellowish to light and dark green, to bright red to deep ruby red — with different sweetness levels. They’re just coming into season now and will continue to be harvested until December; look for piles of them in mercados and stores everywhere.

To prepare tunas — wearing gloves! — first cut off both ends of the fruit. Slit from end to end lengthwise and then peel back the thick skin. It should come off easily.

Peeled, they can be stored for about a week in the fridge in a sealed container or Ziploc bag. The strained juice can be added to margaritas, cooked into a syrup, made into a glaze for poultry or fish or used in smoothies or agua frescas, ice pops or sorbet. Because they’re so sweet, a bit of citrus juice is often added for balance.

Agua de Tuna

One of Mexico’s many fruit-filled aguas frescas, this beverage is quick and refreshing.

- 3 prickly pears

- 1 cup water

- ½ cup fresh-squeezed orange juice

- 1 tsp. agave syrup, honey or simple syrup

Wearing gloves, prepare prickly pears by cutting off both ends of fruit. Then slit from end to end lengthwise, and peel back the skin.

Place peeled fruits in a blender with water. Blend on low for 1 minute. Strain and discard seeds and pulp. (You may need to use a rubber spatula to smoosh the seeds around the wire-mesh strainer and release the juice.)

Pour juice back in blender, add orange juice and sweetener and blend until smooth. Serve over ice.

Prickly Pear Syrup

- 3 lbs. ripe prickly pears

- Water to cover

- 3 cups sugar (approximately)

- 1 Tbsp. citric acid OR 2 Tbsp. fresh lemon or lime juice

Prepare fruits as described above. Put peeled fruits in a pot; add enough water to almost cover them. Cover and bring to a boil. Turn off heat; let steep 30 minutes.

Mash fruit with a potato masher or fork. Using a wire-mesh strainer and rubber spatula, push pulp through and discard seeds. Line strainer with cheesecloth or paper towels and strain juice again.

Measure the strained juice and pour into a pot. Add an equal amount of sugar, and bring to a simmer over medium heat for 5 minutes. Turn off heat, let cool 15 minutes.

Add lemon juice or citric acid. While still hot, pour into clean jars. This will keep for months in the refrigerator. Use for glazes, salad dressings, over desserts, etc.

Tuna-Coco Smoothie

- 2 prickly pears

- About 2 cups fresh or packaged coconut water (not canned coconut milk)

- 1 tsp. fresh lime juice

- Ice

Prepare tunas as described above. Add tuna, coconut water and lime juice, to blender; process until smooth. Strain and serve over ice.

Prickly Pear Paletas

Watch this video to see the whole process for making these refreshing popsicles.

- 8 ripe prickly pears

- ½ cup fresh lime juice

- ½ cup water

- 1/3 cup agave syrup or other sweetener

- ¾ tsp. salt

Using a paring knife, working away from your body, carefully scrape off any cactus thorns. Cut off the ends of the fruit. Using the tip of the knife, score the fruit lengthwise. Slip your thumb under the skin and peel the fruit. Discard the peel and thorns, then dice the fruit.

Prepare prickly pears as described above. In a blender, combine prickly pear, lime juice, water, sweetener and salt; purée until smooth. Pour through a fine wire-mesh strainer; discard seeds.

Pour the resulting liquid into popsicle molds. Freeze until firm, at least 4 hours.

Janet Blaser is the author of the best-selling book, Why We Left: An Anthology of American Women Expats, featured on CNBC and MarketWatch. She has lived in Mexico since 2006. You can find her on Instagram at @thejanetblaser.