Locusts, properly called cicadas, reappear predictably every 13 and 17 years. Sovereign debt crises are less predictably regular.

The last one appeared in 1994, 26 years ago, and the one before that in 1980, 40 years ago. The next one will occur any time now. In fact its epicenter may be traceable to even before the coronavirus outbreak.

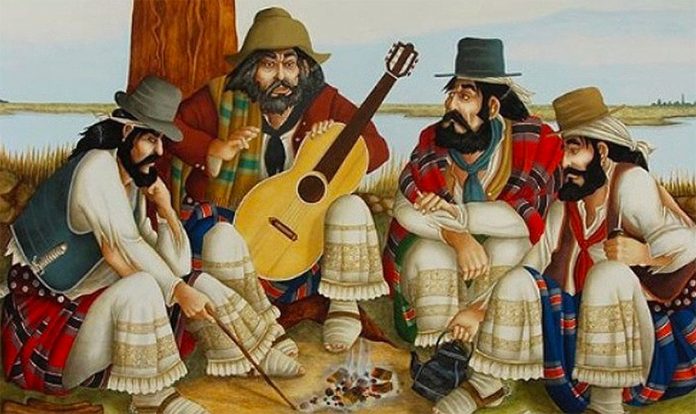

Mexico has been historically so materially affected by sovereign debt crises that the 1994 one was popularly dubbed by the financial press the “Tequila Effect” as it spread from country to country. The finger on the next one should point to Argentina, where the “Gaucho Effect” has already begun, with default a reality.

There are some similarities between prior crises and the impending one, but fortunately for affected banks and countries there are also some differences, positive and negative.

A debt crisis occurs when a sovereign nation cannot pay its debts to foreign lenders. Typically it starts in one country and then spreads to many. In the past, the most materially affected have been in Latin America, in particular in the heavily indebted nations of Brazil, Argentina, Ecuador and Mexico.

Non-hemisphere countries such as Yugoslavia joined in during the early 1980s debt crisis, as did almost all the other nations from the Rio Grande to Patagonia.

In the early 1980s I was the CEO of a regional U.S. bank, materially (more than 10% of assets) affected by sovereign defaults, and as a consequence materially involved in seemingly endless rounds of loan renegotiations and reschedulings.

Sovereign lending had been so profitable and trendy in banking circles that I often lectured on its cost/risk benefits at a prominent U.S. graduate school of business. The industry tone was set by the then-CEO of trend-setting Citibank, who stated that sovereign nations do not default. He was wrong. Citi suffered and if sleepless nights had been on the bill, I would have suffered for being wrong, too.

The commodities price boom which started in the 1990s afforded relief to many rescheduling countries, and the chief difference between then and now is that the world economy today is depressed and expansion and its typically rising prices for everything from copper to oil are on few economists’ horizons. The rolling surge in oil prices for oil exporters such as Mexico and then-solvent Venezuela erased the vestiges of the first and second crises from the books of involved banks, and apparently also from their institutions’ historical memories.

A potentially beneficial difference between then and now is that “then” took place in a high interest rate environment and this was reflected in high, renegotiated interest rates. “Now” base rates on which lending margins are calculated are at recent historic lows, so at least initially set rescheduled loan interest rates will be relatively low.

Another “now” benefit, at least to a handful of countries, is that the remitted proceeds of millions of their nationals working overseas to countries such as Mexico will cushion the foreign exchange shock. In a typical, at least typical pre-coronavirus year, money sent back to the home country ranged from an estimated US $30 billion for heavyweight Mexico to a still significant $10 billion for far smaller Guatemala.

Devaluations are also historically part of the disruption debris of rescheduling. In 1994 Mexico’s peso collapsed: the now-collectible 100,000-peso notes are a stark reminder of the chaos in foreign exchange markets. At today’s exchange rate, the bills would be worth almost $5,000, not the $5 currently quoted by one dealer in obsolete banknotes.

Again, on a positive note, banks in Europe and North America have recently undergone “what if?” examinations, called stress tests. Although the exams no doubt role-played developing country debt rescheduling, they equally doubtless did not foresee a coronavirus-type calamity.

Mexico is the object of a double whammy. A recent Woodrow Wilson Center report from Mexico City pegged the interest tab on state-owned oil monopoly Pemex at $11 a barrel, slightly over half of today’s price for benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil, and well over half the price of Mexico’s higher-sulfur Maya grade. This whammy joins coronavirus.

If I were to guess, or perhaps think wishfully, the renegotiated NAFTA trade accord will be Mexico’s lifeline, with Mexico displacing China as chief supplier to the U.S. of everything from rubber sink stoppers to pre-fabricated factories.

But I’ve been wrong before.

The writer is a Guatemala-based journalist.