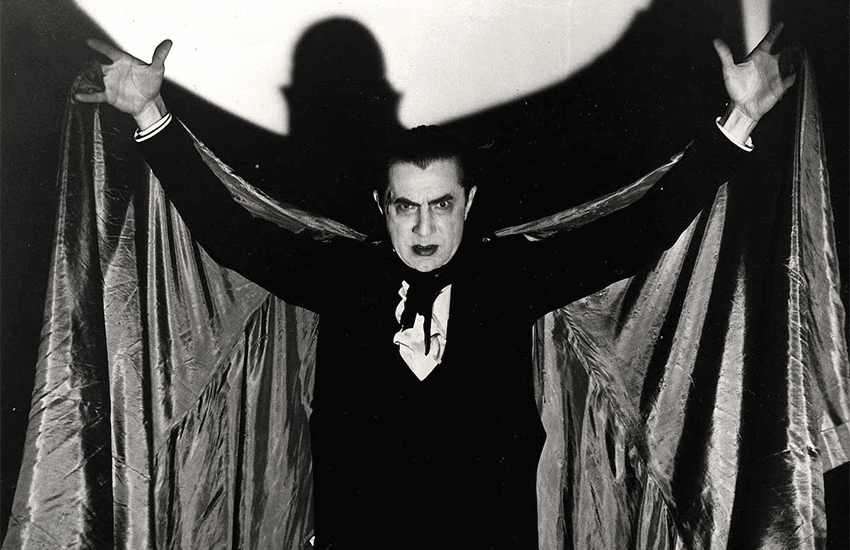

Bats have historically inhabited a shadowy place in the human imagination, and none more so than Desmodus rotundus, the common vampire bat.

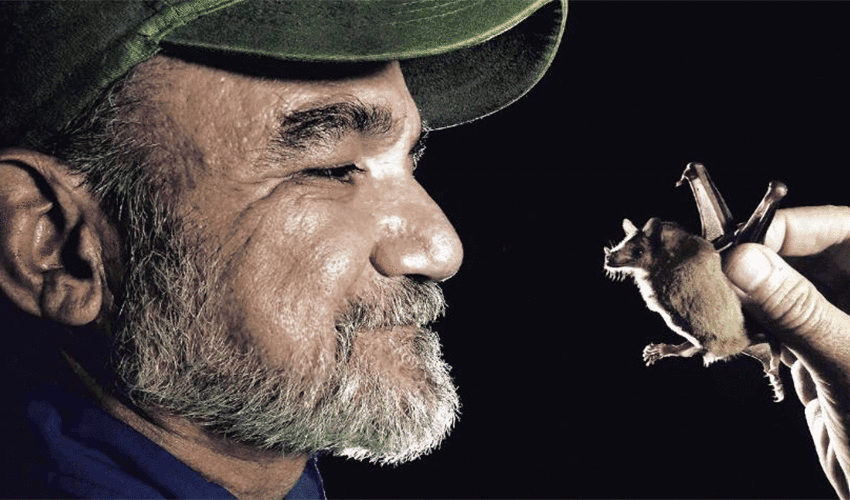

Media portrayals of vampire bat attacks, riffing on Bram Stoker-esque language, represent bats as bloodsucking monsters, terrorizing cattle and human populations alike. Dr. Rodrigo A. Medellín, a unique individual widely known as the Bat Man of Mexico, has a different opinion.

“Vampire bats are a fascinating result of evolution, and we’ve learned a great deal about them and their contribution to biome health, as well as human medicine,” he said.

Even so, the widespread, pervasive effect of media misrepresentation is threatening the conservation of this misunderstood critter.

Beyond their sinister name, vampire bats are, in fact, a largely unassuming species.

Found mostly in the tropical regions of Mexico, as well as in other parts of Central and South America, vampire bats have a number of positive roles to play in everyday ecology. Bats of all varieties, including the vampire bat, play a crucial role in the biodiversity of a range of ecosystems across Mexico.

High on the list is their role as key seed dispersers and pollinators of many desert and tropical plants, including fruit trees, dozens of types of cacti and many kinds of agave plants. This vegetation plays an important role as habitats for a variety of other species, so changes in bat populations necessarily have an indirect biodiversity ripple effect.

And at present, for vampire bats in Mexico, things would seem to be on the upswing. For most wildlife, biodiversity loss and habitat degradation has a detrimental effect, but bats are a generalist species, with high ecological plasticity; in other words, they are adaptable and can change their environment according to necessity.

But with rising global temperatures altering landscapes across the globe, the distribution of the vampire bat in Mexico is changing, with further changes predicted under all climate change scenarios. In general, the transfer of dense tropical forest to grassland for the grazing of cattle favors the expansion of the distribution of this opportunistic creature, a feeder particularly fond of environments modified by humans, where there is a loss of native plant cover and abundant livestock are concentrated in small areas.

These days, bats are most vilified with regard to their negative contributions to public health through the transmission of disease; in Mexico, they are especially demonized as carriers of bovine paralytic rabies.

In terms of vampire bats acting as rabies vectors, however, “We all know that we created the problem,” says Medellín, a professor of ecology and conservation at the Institute of Ecology at the National Autonomous University (UNAM) and a National Geographic Explorer at Large whose work focuses on bat conservation.

“When the Europeans came to this continent in the early 1500s with cattle and horses and pigs, we ‘set the table’ for the opportunistic vampire bats, whose populations expanded greatly. Vampire bats are just one more element in this ecosystem.”

More broadly, Medellín argues that parasitic feeders, such as bats and other native wildlife that concentrates around cattle grazing areas, often become easy scapegoats for the spread of diseases, when there are a number of underlying structural issues in agricultural management that are far more culpable for the voracious spread of the disease — more so than a single species could ever be.

Medellín says that he has “never worked harder than in the past 18 months to defend bats right now from unsubstantiated accusations that [they] gave us Covid. While there are closely related viruses in bats, the Covid virus is categorically not a descendant of the bat viruses.”

Indeed, while scientific evidence suggests that the virus could have transmitted from an animal carrier to the human population, there is currently no evidence that definitively identifies any species as the origin, nor do genomic similarities between other coronaviruses in bats and the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus necessarily indicate bats as the origin.

Similar species prejudice plays into the continued persecution of vampire bats in Mexico, both intentionally and unintentionally, as a result of their role as vectors of bovine rabies.

While annual losses to the livestock industry as a result of rabies are valued at around US $23 million, there are a number of measures that can be introduced to manage the risk of bovine rabies without needlessly culling bat populations. It has been estimated, for example, that vaccinating cattle would bring six times greater rewards than the outlay costs for medication.

Meanwhile, the cost of trying to control vampire bat populations has proved significantly higher than the benefits, not to mention the fact that senselessly attempting to lower bat populations with no consideration of the wider implications will have no immediate benefits for the environment, or even for the likelihood of bovine rabies spread.

It is, however, the easy way out to sensationalize the risk that bats pose as a way of masking issues inherent in the management of livestock across the country, inconsistent levels of rabies vaccination as well as cattle density, to name but a couple. It is easy to ascribe negative traits to creatures that already have a bad rap — think sharks, scorpions, spiders — but when a negative image threatens species conservation, the need to alter public perception becomes urgent.

“Obviously the antidote exists,” says Medellín, “and it is called information. These days, we have more information at our disposal than ever before in human history. But it is so easy to follow false lines of thought — in this case, that many ‘scientists’ have accused bats of giving us Covid, in the process making a ton of money.

“Only through promoting real information and sharing it with journalists, educators, decision-makers [and] the general public can we hope to turn the tide and do justice to these unsung heroes: the bats.”

Shannon Collins is an environment correspondent at Ninth Wave Global, an environmental organization and think tank. She writes from Campeche.