“It is our duty, while inviting you, to discourage you,” the statement read. “Unlike other years, it is not safe.”

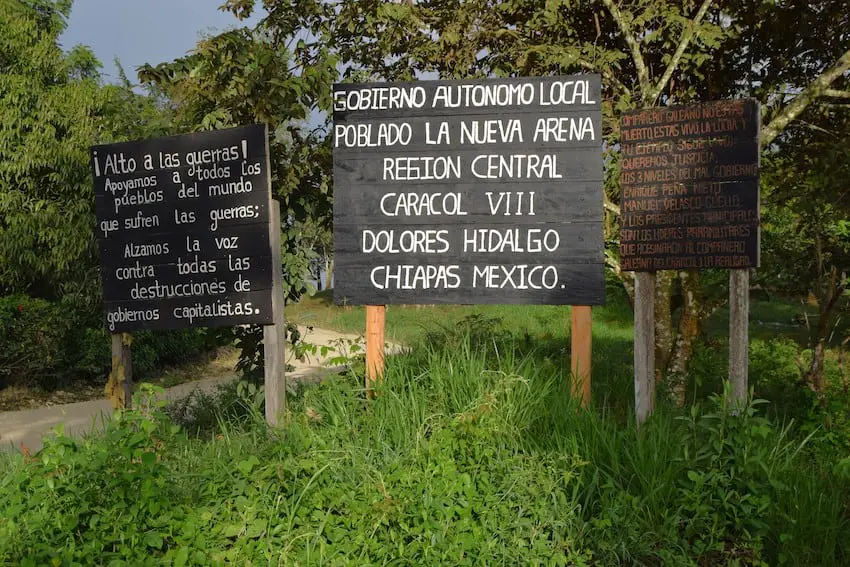

There were other unusual things about the Zapatistas’ invitation to the 30th anniversary of their 1994 uprising, part of a statement entitled “Several Necessary Deaths.” The communiqué railed against the “disorganized crime” engulfing Chiapas and announced the dissolution of Zapatismo’s main governance structures — the Zapatista Rebel Autonomous Municipalities (MAREZ) and the Good Government Juntas (JBG).

Some Mexican media outlets jumped to the same conclusion: On Jan. 1, 1994, the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) had burst out from the Chiapas jungle, taken control of five municipal capitals, and drawn a wave of international solidarity that helped them push the Mexican government into accepting autonomous Indigenous governance systems on redistributed land. Now, it seemed Mexico’s most iconic rebel movement had decided to cede territory to the cartels.

But was that really what had happened? Over the following weeks, the EZLN released a series of 20 enigmatic publications, ranging from political theory to videos of elderly Maya women learning to ride pink bicycles. The last statement announced the location of the anniversary celebration.

It felt too intriguing to miss. In San Cristóbal de las Casas, I joined a disparate bunch of National Indigenous Council (CNI) delegates and European activists, boarding combis for the five-hour drive to the caracol (Zapatista community) where the gathering was to be hosted.

For security, we traveled in a convoy, on a winding road through lush green hills. The mood hovered between festive and tense — we all knew of the war for drug and migrant routes raging between local factions of the Sinaloa and Jalisco Cartels. In recent weeks, clashes between armed groups, local citizens and security forces had displaced hundreds of people in the Guatemalan border region. The violence, combined with stubbornly high poverty levels, was accelerating migration out of Chiapas, including from many Zapatista communities. The EZLN had good reason to be worried.

“Welcome to no-man’s land,” read an EZLN banner over the road — defiant irony is characteristic of the Zapatistas’ messaging — “Everyone’s land, in fact.”

We arrived in a tree-lined valley, a grassy arena with a wooden stage at its head. Around the arena, woodsmoke rose from communal kitchens – one for each of the twelve Zapatista caracoles. There was a kitchen serving free beef stew and coffee to visitors, and an economical dining hall with a more varied menu. The entrance was flanked with technicolored murals and guarded by balaclava-clad EZLN troops, armed with wooden batons and machetes.

Inside, I found myself eating stew with the Puebla delegation of the CNI, who were still buzzing from their successful campaign to shut down a Bonafont bottling plant that had been draining water from their communities. Later, I spoke with the Michoacán delegation about agrarian reform, then with a Hispanic-American activist who was campaigning against gentrification in Harlem, New York. All had been to several EZLN anniversaries before, seeing them as key events to share experiences with like-minded movements from around the world.

As dusk settled, tentless foreigners were shepherded into pickups to be distributed among sheds in nearby Zapatista communities. In the morning, a group of shy Tzeltal youths brewed us coffee in the ruined house of the former landowner, who fled during the 1994 uprising.

We were told the pickups would be back for us at 9 a.m. This turned out to mean 8 a.m., as the EZLN follows “resistance time,” which is an hour ahead of “bad government time.” The difference caused much confusion throughout the gathering to the amusement of the Zapatistas, who say time is a capitalist construct, anyway.

The theater performance the Zapatistas staged for New Year’s Eve was a similar blend of ideological earnestness and mischief. Act One recounted the Zapatistas’ history of marginalization and rebellion, ending with them overthrowing the abusive master to reclaim their ancestral land. Act Two decried the ravages of capitalism, featuring a confused child narrator, dancing skeletons, and a cardboard Maya Train, which the EZLN fears will displace them from their hard-won territory.

Act Three laid out the threats now facing Zapatismo — from drug traffickers to manipulative aid programs — and explained the Zapatista restructuring announced weeks before. It insisted the announced dissolution of the overarching governing bodies was not a defeat. Rather, the MAREZ and the JBG had been replaced with hyper-local assemblies called Local Autonomous Governments (GAL), which would make all community decisions via direct democracy. All property would be held in common, all work and services organized collectively, and like-minded migrants welcomed to join the communities. The aim was to invert the pyramidal hierarchy, decentralize power and make decision-making faster. Whether it would also help withstand cartel violence was less clear.

As night fell, masked EZLN militias silently formed ranks on either side of the arena, men facing women. The sight of the uniformed troops sent a hush over the valley, incongruously broken by “17 Años” — a controversial cumbia about dating an underage girl — that blared from the soundsystem. The militia-women opened the parade, clacking their wooden batons to the beat, before peeling off to do joyous skips around the field as the men took up the march. The advancing columns pushed us toward the stage — to the sentimental strains of “Como Te Voy a Olvidar?”

Flanked by empty chairs representing fallen comrades, Subcomandante Moisés — successor to the EZLN’s original spokesman, Subcomandante Marcos — stood to give the midnight address. My watch read 11 p.m. (bad government time).

“We are not here to remember the fall of these comrades 30 years ago,” Moisés said, first in Tzeltal, then Spanish. “We are not trying to be a museum… The people must govern themselves!” He underlined Zapatismo’s new emphasis on communal property — a further step to the political left that, he admitted, was not sure to gain the support of the wider movement.

“We are alone, like 30 years ago,” he concluded. “We have only discovered the path we are going to follow: communally!”

The tone felt more ominous than celebratory. But for the Zapatistas, failure has always seemed guaranteed. The diverse Indigenous communities of Chiapas were once so isolated, they had to learn Spanish even to communicate with each other. In 1994, many faced the Mexican army carrying wooden guns. Their triumph is that somehow, they are still here, an inspiration to political underdogs around the world.

The EZLN now faces a new crisis, and they don’t know if their strategy is going to work. But their message remains the same: For the underdog, success is never certain. All you can do is try something different, and see what happens. And it helps to have a sense of humor about it.

A burst of fireworks broke the tension, and we spent the first hours of the new year dancing exuberant multi-national cumbias. The next morning, the EZLN militias seemed relaxed and chatty, as the stage was opened to presentations by outsiders. There were revolutionary ballads, interpretive dances, an Indigenous Mexica ceremony and — by far the most popular among the young Zapatistas — a rapper who kept calling to turn the sound system up.

The previous day, I had felt uncomfortable taking part in the sea of camera phones pointed at the Zapatistas. But by now, I realized there were at least as many Zapatistas pointing camera phones at us.

Despite Subcomandante Moisés’ message, the Zapatistas are less alone than they used to be. They can communicate with activists around the world, and watch reggaeton videos on YouTube. We all now have the means to study each other, and perhaps the EZLN’s future really depends on which messaging gains the loyalty of their newly online youth.

Cat Rainsford is a journalist and researcher who has written for InSight Crime, The Guardian, New Lines Magazine and others.