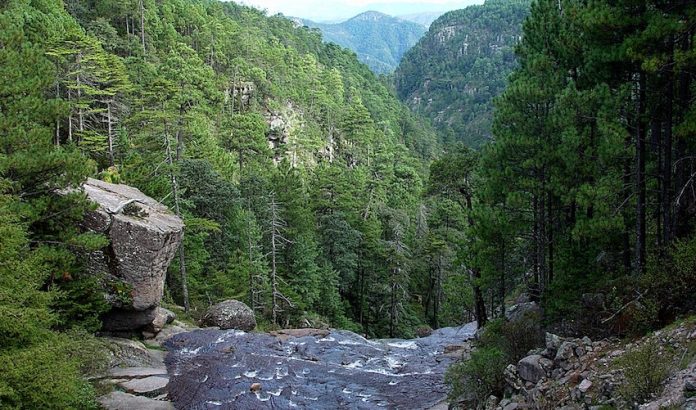

The Mexiquillo nature park and reserve in La Ciudad, Durango, began as a few cabins built 25 years ago in the high sierra mountains to take advantage of people looking for a cool respite from higher temperatures in the lowlands. Today, it offers so much more.

At 2,560 meters above sea level, these rugged mountains on the Durango-Sinaloa border are close to — yet a world away — from both the desert city of Durango and the hot and muggy Pacific coastline — where most of Mexiquillo’s visitors come from.

Mexiquillo is one of a number of high-mountain retreats along the Sierra Madre Tourist Corridor, which includes other natural areas such as Otinapa, Puentecillas, Coscomatte and Arroyo del Agua. All these share vast expanses of forested peaks, some of which are still virgin.

But as Elvira Silverio Díaz of the state tourism agency notes: Mexiquillo offers not only a convenient location but unique natural and man-made features as well, which are bringing more visitors from further away.

After entering the park, the first natural attraction is the Jardín de las Piedras (Rock Garden), an area filled with otherworldly, rounded rock formations overlooking deep ravines. Sujey Delgado, owner of Hostal Mexiquillo, a hostel located in the park, says that science knows little about the rocks’ geology but that their “magic” draws people to climb on them.

Hollywood has used them in scenes, such as in the film “Caveman” (1981). Delgado offers a night tour to see the stars from them, and — believe it or not — as far away as Mazatlán’s lighthouse beam.

Nearby is a waterfall that is easily accessible and popular for wedding photos, as well as some ponds that were accidentally created by engineers working in the area over a century ago.

Those same engineers also created eight unfinished tunnels that were blasted into mountainsides, part of a project to connect Mazatlán and Durango by rail. The project met its demise with the construction of a highway between the two cities in the 1940s — today the toll-free highway.

The rail construction is likely the origin of the park’s name, says Delgado. The engineers came mostly from Mexico City and decided to name their encampment Mexiquillo, which translates to “little Mexico” — Mexicans often use the term “Mexico” to mean Mexico City.

This name was chosen when the local community — the La Ciudad ejido (a government-granted communal land parcel) — decided to take a portion of their forest and create a tourist attraction. “Mexiquillo” and “La Ciudad” are often used interchangeably by visitors, but the first officially refers to the park and the latter to the ejido.

Originally the ejido was created after the Revolution to allow locals to continue their traditional lives, which revolved around logging and other forestry activities. However, in the late 20th century, these activities came under pressure from federal environmental authorities. The park, and its first cabins, were a response to this, to look for a way to recover lost income. Slowly, the area gained a local, then regional reputation as a way to spend a weekend in the cool forest.

Nonetheless, the number of visitors and cabins, both on and off the ejido, have grown sufficiently that most locals see the value in conserving the forest and its ecosystem. Forestry has not been eliminated, but tourism now accounts for half of the economic activity. The ejido’s abandoned sawmill at the park entrance testifies to the economic shift.

Local businesses like Hostal Mexiquillo also show how the ejido is evolving. It originally was Delgado’s father and grandmother’s home, on a plot given to the family as ejido members. When the park opened its doors, her father began adding rooms to rent.

Today, the hostel has dormitories, an educational mushroom fruiting chamber, meeting rooms and a new, large cabin. The hostel receives visitors from all over Mexico and from abroad, and Delgado offers tours because “…it is important that people understand the culture, environment and people who live here.”

Today, Mexiquillo acts as a kind of ambassador to the ecotourism possibilities of the Durango-Sinaloa border. It introduces outsiders to hiking, mountain biking, birdwatching and other ecotourism activities which are an important part of tourism in the region. Mexiquillo/La Ciudad also offers “rural tourism,” with local cheeses and breads available. Wild mushrooms are so important in late summer that there is a festival dedicated to them in August.

High season runs from June to October, when the lower altitudes have their highest temperatures. However, the area can receive visitors in the winter, especially when it snows. This draws people unfamiliar with winter precipitation, and also prompts authorities to issue warnings, as even the toll road can be rather slippery.

Mexiquillo got lucky with the building of the Mazatlan-Durango toll road over a decade ago. Most small towns and attractions die when superhighways are built. But the new highway makes the trip easier and faster as there are exits relatively close to the park, allowing people to avoid dangerous older roads such as the infamous Espinazo del Diablo section of the non-toll highway.

More people can and do come from further away, especially from the Sinaloa side, but the area also regularly sees visitors from much of northern Mexico, especially during holiday periods.

Mexiquillo is a good example of how tourism can help an area adapt to new environmental realities, but there are still challenges. Logging has not disappeared, nor does anyone expect it to anytime soon. More importantly, says Silverio Díaz, there has been environmental damage associated with the park’s growth, especially in the last decades. Some is from the use of ATVs, but the most significant impact has been from the almost wild building of cabins, especially on non-ejido land nearby.

Crowding and traffic is also becoming a problem, especially at peak times. For these reasons, Durango state authorities are considering development of future high-sierra locations with more care.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture, in particular its handicrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily.