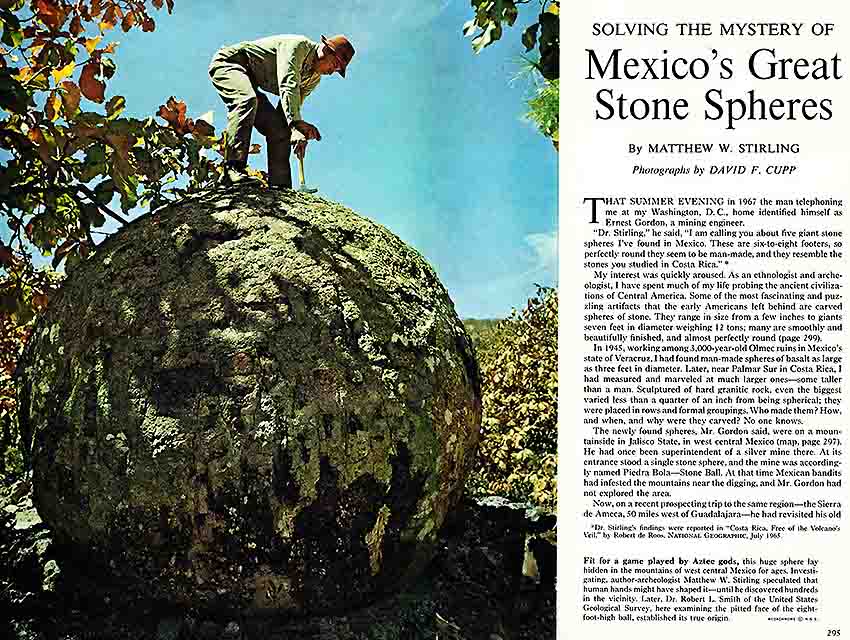

The Piedras Bola Silver Mine, located in Jalisco’s Sierra de Ameca, is named after a giant stone ball lying just outside its entrance. In 1967, the former superintendent of the mine, Ernest Gordon, was shown five more huge stone balls in the hills above the mine, prompting him to place a telephone call to archaeologist Matthew Stirling in Washington, D.C.

Stirling — a pioneer who headed the Smithsonian’s Bureau of American Ethnology for several years and is known for his discoveries about the Olmec civilization and for being an early advocate of the idea that they predated the Maya — had published reports of granite balls he had found in Costa Rica, sculpted by human hands centuries ago.

The balls that Gordon had found in Mexico appeared to resemble the ones studied by Stirling. “These are six to eight footers,” Gordon told Stirling, “so perfectly rounded, they seem to be manmade.”

In December of 1967, Gordon led him to the site on top of the mountain where the balls sat, 65 kilometers west of Guadalajara, in Ahualulco, Jalisco. Today, it’s a nature reserve and park.

“Such great numbers surely indicated natural formation,” wrote Stirling in an article in the August 1969 issue of National Geographic.

For the article, Nat Geo asked USGS geologist Robert L Smith to explain just how Mother Nature had formed all those nearly perfect spheres. The word of a scientist was definitely needed since the best that local legend could come up with was that these hills had once been inhabited by giants and the Piedras Bola had been their canicas (marbles).

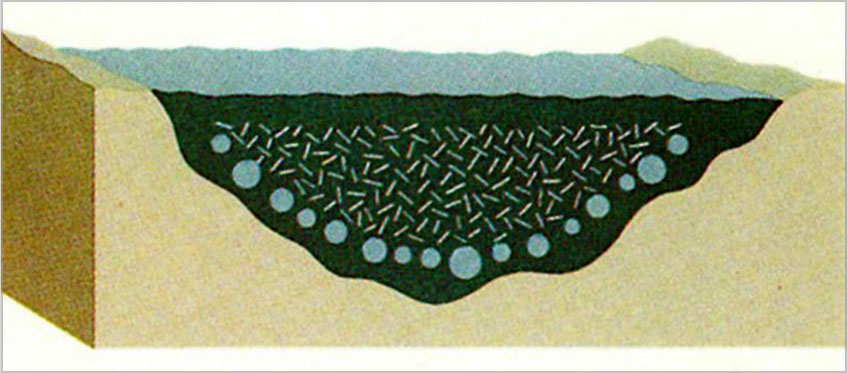

Smith told the magazine that a pyroclastic flow of hot volcanic ash had blanketed the area long ago. Deep below the surface, the volcanic tuff began to crystallize “in the nuclei of single glass particles,” forming small balls that slowly grew larger with time, resulting in the stone balls in the hills above Ahualulco.

In 2007, the University of Guadalajara (UdG) published a 266-page book on the Piedras Bola and their surroundings. Here we find another analysis of the origin of the giant stone balls.

The UdG team suggested that lava bombs and incandescent blocks were falling into the pyroclastic flow. As the flow passed through narrow valleys, they created turbulence, causing these intrusive lava lumps and blocks to rotate and become coated with layer after layer of hot tuff — snowballing into spheres of various sizes.

The Nat Geo and UdG theories were the only credible explanations I had heard of up until a few days ago when I headed for the Piedras Bola with a group of ornithologists.

I had last seen the site in 2013 when my goal was to measure the largest of the megaspherulites (i.e., the stone balls) for myself.

Now, nine years later, I wanted to revisit the Piedras Bola because I had heard rumors that the nature reserve had been abandoned by local authorities and was falling into ruin.

Riding in a sturdy Tacoma with four-wheel drive, we turned off the Ahualulco-Ameca highway onto the 6-kilometer dirt road leading there. We passed the now dysfunctional ziplines and hanging bridge, into which officials had poured a great deal of money, which critics say could have been used to build a better-quality access road.

Unfortunately, the road they did build deteriorates badly after three-quarters of the way, and you now need four-wheel drive to make it all the way to the top. The rough state of the road is matched by the deplorable state of the facilities which had been built to welcome visitors.

The outdoor theater for visitors that was built there is now overgrown with weeds. All the wooden bridges have fallen to pieces. Signs meant to orient visitors are now just about unreadable.

As we hiked up the trail to the Piedras, the organizer of this trip, Canadian geologist Chris Lloyd, mentioned that in his examination of the stone balls, he had never seen any evidence to back up the two theories of their origin which I have mentioned above.

“Let’s take a look at some of the balls which have split open,” he suggested.

We only needed to walk 200 meters to find an example. The composition of the balls on the inside was completely homogeneous.

If the UdG theory was correct, we should have found a foreign object inside the ball. And if the National Geographic explanation was accurate, there should have been evidence of a crystal structure, such as a repeating pattern or radiating lines. But we could see nothing of the sort in any part of the balls.

We wandered up the hillside, which is strewn with these huge balls, until we came to a rock formation popularly known as La Calavera, The Skull, which is taller than it is wide. It is naturally connected to the bedrock and is not an independent unit like the balls all around it.

“This,” said Lloyd,” is showing us what’s really going on here. Look at the onion-skin weathering on the top.”

Yes, we could easily see that thin layers of rock were spalling off the top of The Skull (La Calavera).

What we were looking at, it seems, was a Piedra Bola In the making. Maybe in another thousand years or so it will weather to a nice round shape and, now disconnected from the bedrock, will roll down the hill to join the other members of the family.

Having reflected on La Calavera, we began to notice many other examples of rock protrusions that had weathered into nicely rounded curves. They were, in fact, partial balls.

I suddenly realized that all the previous theories about these rocks had assumed that — apart from the stone balls lying on the surface — there were hundreds more of them underground, just waiting to be liberated.

If erosion is what creates the spheres, it means there is solid rock under the surface, here at the top of the hill, not hundreds of balls waiting to be liberated. It would indicate that all of the balls, those up here and those that later rolled down the hillside, were formed long, long after the pyroclastic flow had solidified and they got their round shape through a simple process of weathering.

A little while later, on the trail, Lloyd pointed to the ground. We could see that the rock beneath our feet was broken up into squares and some of these squares exhibited the same onion-skin weathering we had seen on the big balls, but here it was happening on a very small scale. Smaller versions of balls were forming right there on the trail!

The mystery of the stone balls having been clarified (in our eyes), we walked 500 meters northwest, beyond The Skull, to the area known as Las Torrecillas (The Little Towers).

If you think the Piedras Bola are curious, here you can see a phenomenon even curiouser: stone balls perched on top of natural columns about 4 meters tall. The columns are composed of relatively soft material that was eroded away by rainfall — except directly underneath the ball.

Over the years, the number of torrecillas has been reduced, and today there is only one good example left. If you want to see it, better plan a trip quite soon because the ball on top of what I’m calling The Last Tower seems to be held up there only by spit and a prayer.

Yes, if you want to visit the Piedras Bola and work out your own theory of how they were formed, do it now while The Last Tower is still standing and the road is still driveable. It’s well worth the effort.

After finding yourself a four-wheel drive vehicle, check out my Wikiloc route to the Piedras Bola. Driving time is about two hours, whether from Guadalajara or Lake Chapala.

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.