The age of modern tourism began after the Second World War, largely thanks to advances in commercial airline travel that made reaching international destinations faster and easier than ever. Indeed, this era marked the beginning of people viewing cities and attractive places as destinations, and the onset of destinations actively marketing themselves to tourists.

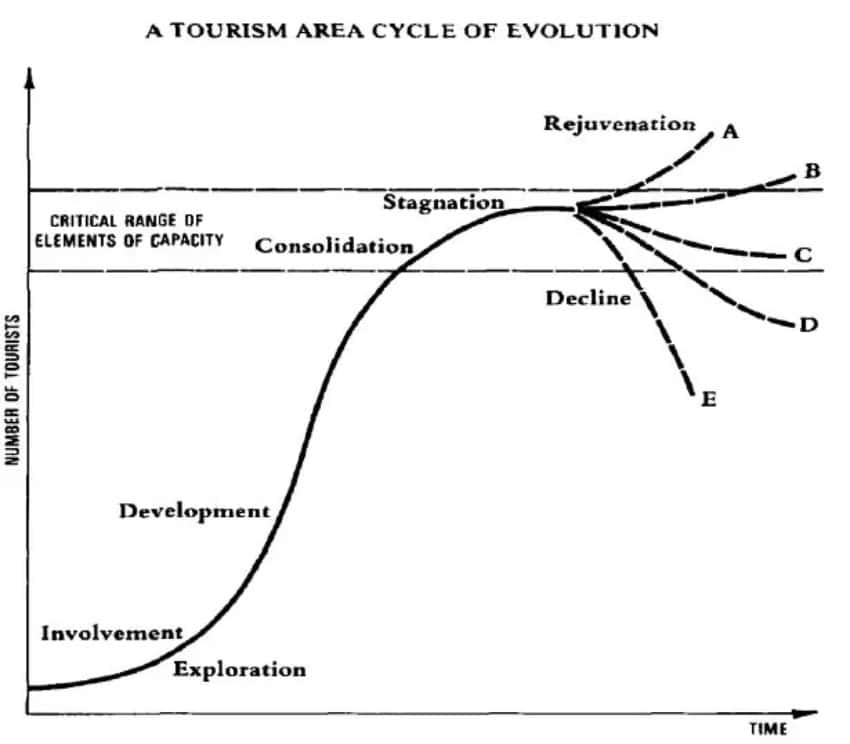

Academic studies of how these tourist destinations developed over time followed, perhaps the most influential and enduring of these being Professor Richard W. Butler’s concept of a Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC), first published in The Canadian Geographer in 1980.

Butler’s model for how tourism destinations evolve posited six stages, the first five of which are exploration, involvement, development, consolidation and stagnation. The final stage offers several possibilities, ranging from rejuvenation to decline or even outright collapse of tourism due to external factors (the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 provided a thankfully brief example of how this might happen).

Of course, no two tourist destinations are the same. Nor is there any timeline for how long each of these stages might take. But given the lasting impact of Butler’s theory and the rapid growth in Los Cabos in recent decades, it seemed interesting to explore where Los Cabos is in its evolution, according to Butler’s model, and thus what the future might hold.

Exploration

The first stage occurs when a small number of tourists discover a place, likely because of a single exceptional attraction. In the case of Los Cabos, it was fishing. The reputation for the spectacular fishing throughout the Baja California peninsula began to be spread by Western Outdoor News writer Ray Cannon to U.S. audiences in the 1950s.

The first two lodgings in Los Cabos in response to this exploratory phase were the Fisher House, a guesthouse rather than a hotel, which was opened by Carmen Fisher in San José del Cabo in 1951; and the Hotel Las Cruces Palmilla, which opened in 1956 with but 15 rooms. Intrepid travelers of the time were few and obliged to fly down and land on Palmilla’s airstrip, or come by boat, since there were few roads and no commercial air service nearer than La Paz.

Butler noted that there is little economic benefit for locals in this stage, and with few exceptions, that was the case in Los Cabos.

Involvement

By the time Los Cabos was featured in a Sports Illustrated article in 1965, Los Cabos had been placed on the tourism map, not only for its fishing, but also for some notable new hotels: the Hotel Cabo San Lucas in 1961 and the Hotel Hacienda in 1963, the latter the first lodging to open in Cabo San Lucas.

By then, locals had become more involved in tourism, as Butler predicted would happen in the TALC’s involvement stage, and a defined tourist season was being established. There was also more pressure to improve transportation options to the destination, although these wouldn’t come to fruition until the following decade, when the Transpeninsular Highway was completed — allowing people from the U.S. to drive the length of the peninsula for the first time — and the Los Cabos International Airport opened.

Development

According to Butler, tourists arrive slowly at first before eventually there is a rapid rate of growth. For Los Cabos, this happened only within the past 15 years, as the graph above suggests, with two brief dips due to Hurricane Odile in 2014 and the pandemic in 2020.

However, there was a long run-up to this phase, and it seems clear that Los Cabos first entered the development stage, as Butler defines it, in the early 1990s. That’s when local control of tourism declined as large brands began moving in, beginning with the opening of Westin and Hilton properties in 1993 and 2002, respectively, with more hospitality chains following in their wake. This period also saw the development of attractions beyond fishing and beaches, with luxury resorts featuring spas, upgraded swimming pools and significantly improved dining options increasingly becoming the norm.

This is also the first stage where locals began to see changes to the area that they didn’t approve of, which was true as early as the 1990s.

Consolidation

“As the consolidation stage is entered, the rate of increase in numbers of visitors will decline,” Butler pointed out, “although total numbers will still increase, and total visitor numbers exceed the number of permanent residents. A major part of the area’s economy will be tied to tourism. Marketing and advertising will be wide-reaching and efforts made to extend the visitor season and market area.”

Los Cabos has likely entered this stage now that growth has slowed significantly. This year, per Rodrigo Esponda, managing director of the Los Cabos Tourism Board (FITURCA), tourism growth should finish at about 2.5%, with 3% forecast for next year. Which is to say, quality is now prized above quantity.

These figures argue for placing Los Cabos in the consolidation stage, even though other Butler hallmarks for it — well-defined tourism districts, widespread marketing and advertising — were seen during what I have described as Los Cabos’ development stage. A growth in opposition to tourist projects, another Butler staple of consolidation, is also present.

Stagnation

“One aspect of the model that has become more relevant over time,” Butler has written since his theory was first published, “is the relationship implied between level of use and quality of experience.” Meaning that the more people that come to a destination, the more likely they are to degrade the quality of the natural attractions that spurred tourism in the first place.

This is undoubtedly happening in Los Cabos. Fish populations, for example, have been declining regionally for decades, and scarcely any views of the ocean can be seen along what is now termed La Ruta Escénica, which, 20 years ago and before, was truly spectacular. It’s also clear that developments are reaching farther up the Pacific Coast and East Cape, encroaching on natural treasures like the Cabo Pulmo National Park.

It’s likewise true, as Butler foretold, that Los Cabos is starting to lose its fashionable image. But until other trendier destinations arise and Los Cabos actually reaches its peak in terms of tourism numbers — unlikely any time soon, given infrastructure improvements to the Los Cabos International Airport and elsewhere — Los Cabos will continue to fight off stagnation. It bears noting, for instance, that area resorts collectively have never been of a higher quality than they are right now.

The final stage

The final stage, according to Butler, offers five potential outcomes. Two of them, modest growth or complete rejuvenation, suggest a rosy future. The other three — decline, capacity levels cut to stabilize decline, and the total collapse of tourism in the destination due to war, pandemic or other external factors — represent varying degrees of calamity.

Assuming Los Cabos solves its water problems — a big if considering the municipality has been operating at a deficit for quite some time — then I would consider continued moderate growth the likeliest outcome, especially if the Los Cabos Tourism Board continues to be so efficiently managed, and with such foresight. But the future, as always, remains beyond the conception of any model, however well thought out.

Chris Sands is the former Cabo San Lucas local expert for the USA Today travel website 10 Best and writer of Fodor’s Los Cabos travel guidebook. He’s also a contributor to numerous websites and publications, including Tasting Table, Marriott Bonvoy Traveler, Forbes Travel Guide, Porthole Cruise, Cabo Living and Mexico News Daily.