I am a child of the NAFTA generation. I first came to Mexico during my junior year in college – a business student motivated and inspired by the promise of a free trade agreement that would bring new opportunities. While other students went off to study in Barcelona or Madrid, I chose Guadalajara, Mexico. I wanted to learn everything I could about the country.

After graduation, I interviewed for a Wisconsin-based company interested in doing manufacturing in the United States and Mexico for export around the world. They sent me, a 21 year-old kid, to Mexico City for an interview.

I remember the lunch interview in Polanco at a fancy restaurant, and being put up in a hotel on Reforma Avenue. I could not have been more excited! The company hired me and for years, times were very good. The company invested in manufacturing and talent in both Mexico and the United States and we were competitive, successful, and sold our products around the world.

But then, we started feeling competitive pressure from companies in China, who offered impossible prices and incredible production turnaround times. The company went to Asia, first to Taiwan and trade shows in Hong Kong, but ultimately to China. A few initial exploratory trips turned into me traveling over 50 times during a six-year period as we relocated manufacturing out there, out of the US and Mexico.

The allure of such low costs, flexibility and lightning-fast production made the decision to move to China hard to resist. It seemed like everything there was possible – it was a manufacturer’s dream.

We all know how this story has turned out. Nearly every manufacturer around the globe did the same thing for years, but then things began to shift. China started to become more expensive. China demonstrated a complete lack of intellectual property protection that resulted in many companies finding competitors popping up almost overnight with an identical product at a much lower price. China started to lose appeal.

Ironically, it was the administration of U.S. President Trump that pushed through two initiatives that began to change the balance of business power from China to Mexico: tariffs on China, and the updated US-Mexico-Canada (USMCA) free trade agreement. When the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted supply chains around the world, there was even more incentive for companies to look elsewhere.

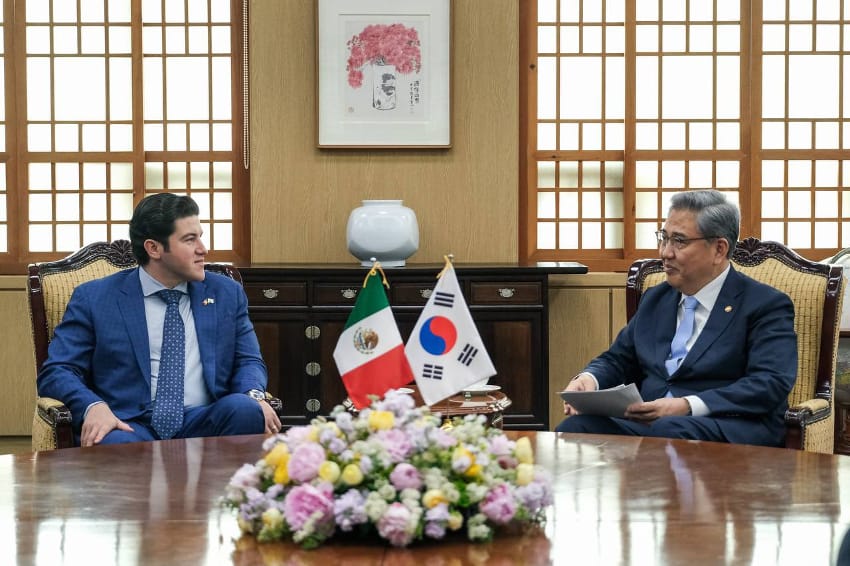

After losing investment to China for years, Mexico is now getting the business world’s attention again. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is at record levels and the investment is coming in from around the world. Companies from Germany, France, Italy, and The Netherlands lead the investment from Europe while China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan and India lead the investment from Asia.

Companies from the U.S. and Canada are more active than ever. Perhaps most tellingly, China was listed second only to the U.S. for planned investments in Mexico this year, according to the Economy Ministry. In my opinion, Chinese companies see very clearly that a divided world is becoming a reality and they must have a second manufacturing base outside of China that allows them access to the U.S. market.

Some question Mexico’s ability to respond and react to this opportunity. My response is: no country is perfect for investment. The BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) countries, which were seen as rising stars, have lost some of their luster.

Europe is struggling with unpredictable energy costs, significant supply chain issues due to the war in Ukraine, and restrictive labor policies. The U.S. is clearly benefiting from the nearshoring boom with manufacturing returning to the country, but it also has low unemployment today, unpredictable immigration policies and increasingly high labor costs.

Mexico, the U.S. and Canada are in the midst of a once in a generation opportunity. If you aren’t in one of the big cities or manufacturing hubs of the country, it might be harder to see, but nearshoring to Mexico is real. A lot of good jobs are being created that provide a stable income, benefits, healthcare, and employee training. Jobs that provide a stepping stone into the middle class. Jobs that improve lives by keeping families together, instead of forcing one family member to go abroad to look for work. Jobs that pay taxes to governments that in turn can improve education, healthcare, and infrastructure.

I believe that the current nearshoring boom will result in significant benefits that will impact North America as a whole. We should embrace these potential benefits, and hold businesses and governments accountable to ensure that they in fact become reality.

It’s a great time for Mexico, and I personally couldn’t be more excited to see the world’s attention again on Mexico, almost 30 years after many first saw the promise of investing in this great country and its people.