With the new Tesla plant coming to Monterrey, the Mexican press has been all abuzz about “nearshoring,” and the idea that Mexico could rival Asia as a global manufacturing hub.

Iván Rivas of the Nuevo León Economy Ministry calls it a “… wave of economic opportunity for Nuevo León, with foreign investment as well as domestic … leading to an export economy.”

Nearshoring refers to international companies moving factories and other business infrastructure closer to the world’s largest market for their goods: the United States. As has been much reported in the media, the impetus for this particular move is a combination of logistical and political issues related to China, which has been “the world’s factory” for several decades.

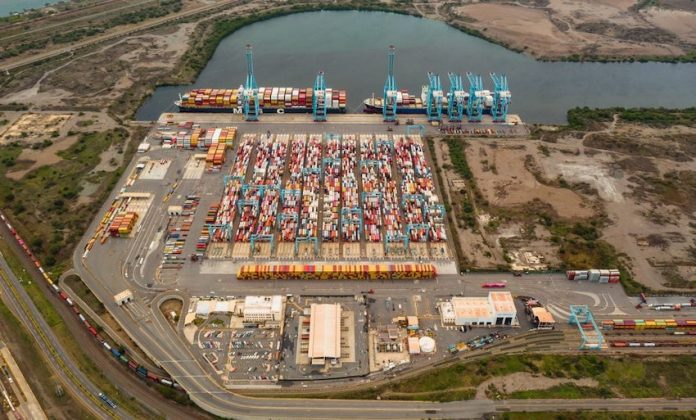

Rivas and many others are quick to point out Mexico’s huge advantage: its proximity to the U.S., which means more reliable, flexible and cheaper shipping options. Recent years have seen companies from North America, Europe and even Asia build facilities, as noted by the abundance of new industrial parks from Monterrey, Nuevo León southward into Querétaro.

But foreign investment in Mexico is nothing new. Latin American economics expert Michael J. Twomey, Professor Emeritus of Economics at the University of Michigan, Dearborn, says that what we are seeing is really “…the newest phase of Mexico’s economic development in relation to the rest of the world…” with many of the same factors that Mexico has faced before with foreign investment.

Since Mexico’s independence, foreign investors have been attracted to Mexico for one or more of the following reasons: natural resources, inexpensive labor, government enticements and proximity to the United States. Notable early examples include European textile mills and the revival of many colonial-era mines by the British.

The government of Porfirio Díaz (1876–1911) gave great incentives to foreign-owned industry, but to the detriment of many Mexicans — this was one cause of the Mexican Revolution.

In the 1960s, Mexico began offering tax breaks to factories on the border doing assembly work, which was followed by the development of an auto manufacturing industry. Volkswagen has had a plant in Puebla for decades, and more recently, Kia opened a plant in the state of Nuevo León. Both operations have been large enough for long enough to establish German and Korean communities in the two states respectively.

What makes nearshoring different from previous investment cycles is not what Mexico is doing but how much it depends on what the U.S. and China are doing.

Twomey believes that it will be a matter of if and how China adapts to the new global reality and how much the U.S. “paints itself into a corner” through anti-Chinese tariffs and other trade policies.

Mexico does have other unique advantages: although other Latin American countries could take advantage of geography, Mexico has a far better developed industrial infrastructure along with free trade agreements such as the USMCA and the IMMEX program.

While Mexico’s relationship with the U.S. is not perfect by any means, it is certainly better than China’s relationship with that same country.

At least for the short term, few doubt the economic impact that the global production shift has had on Mexico, even if there are no national statistics about the number of foreign operations moved here or jobs created. Mexico’s Economic Research and Teaching Center (CIDE) estimates that nearshoring will generate around 150,000 engineering jobs. By 2025, Mexico will need to produce about 5 million workers in STEM, it says

Jorge Martinez of Think Tank Financiero at the Tec de Monterrey university also forecasts a boom in the energy sector, education and commercial and residential construction. A number of schools have already made changes to accommodate this growth. The University of Monterrey recently responded similarly to the so-called “Tesla effect” with a curriculum update.

Mauricio Peña of Outbound Mexico sees the surge of foreign manufacturing growing Mexico’s expatriate population as companies send contingents of mostly managerial staff to supervise construction, set up and oversee local teams. But it is not limited to the industrial parks.

Edyta Norejko of ForHouse real estate services has seen impact in mostly industry-free Mexico City. She is currently working with an aeronautical company building a factory in San Luis Potosí but needs housing for executives in the capital.

But aside from the possibility that China and the U.S. find some way to patch things up, there are other challenges to a nearshoring revolution in Mexico: energy expert Ramses Pech has opined in the newspaper Milenio that Mexico’s energy infrastructure is inadequate and becoming more so. He doesn’t see the political will to make the necessary investments to meet current or future demand.

Other criticisms of the Mexican government include that it doesn’t do more to make Mexico appealing, such as providing a more certain regulatory environment and — perhaps more importantly — clamping down on organized crime, which targets the flow of trucks northward to the U.S.

But perhaps the biggest risk to all this foreign investment is that a strong dependence on exporting to the U.S. could compromise Mexico’s economic and even political independence.

To date, the type of manufacturing being done here is limited, often consisting of the assembly of final products with imported parts. This is particularly true with Chinese investment. China ships parts like chips and batteries, and Mexico assembles electronics and other consumer goods.

This setup not only allows China to handle some of its logistical issues but also helps them get around U.S. tariffs, as long as the correct percentage of the final product’s parts were made in the USMCA trade zone. Whether foreign companies will expand their operations into other products remains to be seen.

Nearshoring’s effects are not evenly distributed in the country. Most of the benefit has been in the northeast and central part of the country, with about half of foreign investment going to the Monterrey area, says Martínez. Twomey adds that only areas that have invested in technology have benefited, as there has not been any national-level push either in education or infrastructure by the Mexican government.

Twomey also notes that how Mexico fares with nearshoring has as much to do with its relationship with China as its relationship with the U.S. He notes that Mexico is in the middle of a larger dispute between these two countries, with little control on how that plays out.

With China making its presence felt in various parts of the world (economically and diplomatically), Mexico needs to be careful that it doesn’t wind up trading one dominant trading partner for another.

Leigh Thelmadatter arrived in Mexico over 20 years ago and fell in love with the land and the culture in particular its handcrafts and art. She is the author of Mexican Cartonería: Paper, Paste and Fiesta (Schiffer 2019). Her culture column appears regularly on Mexico News Daily

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Mexico News Daily, its owner or its employees.