I’m on the campus of the Universidad Marista de Guadalajara (Marist University of Guadalajara) and the place is buzzing with activity. In just about every classroom, corridor and auditorium, teams of girls ranging in age from eight to 18 are talking to members of the general public, including members of their own families and communities.

These girls have spent the last few months developing their own smartphone applications and are now happily explaining how they work to anyone who approaches them.

Every one of these apps, I discover, has been developed in response to a perceived problem. At the beginning of the project, all the girls were given the same challenge: to identify an issue in their community and develop an app that can help resolve it.

This is all happening through the Jalisco chapter of Technovation, a tech education nonprofit based in Los Angeles, California. Through Technovation Girls, its free global, free, technology education program for girls ages 8 to 18, Technovation has helped 350,000 girls and young women in 120 countries become technology leaders and entrepreneurs.

Every year, thousands of girls who work in teams of up to five and are assisted by 19,000 volunteer mentors participate in Technovation’s 12-week program, developing a working prototype for an app meant to solve a real-world problem in their communities.

Along the way, they develop their computer, design, collaboration, problem-solving, marketing and leadership skills.

At each display, I can get an idea of what young Mexican girls see as problems in their country or region.

Not surprisingly, many of the apps deal with nutrition, unemployment, security or stress, but some offer help for depression or even for the nationwide problem of enforced disappearances.

When I walk up to a stand labeled Work Now, I find five girls from the little town of Cocula, whose claim to fame is being as “the birthplace of mariachi.”

“What does your app do?” I ask them.

“As the name implies, Work Now gets you a job,” says Anay Camacho. “We live out in the country, where unemployment is one of the biggest problems — which is why so many country people go looking for work in the U.S.

The whole problem got a lot worse after COVID-19 came along, said Camacho.

“So we created this app, which simply connects people looking for a job with businesses looking for workers.”

At the other end of the room, I saw a big houseplant beneath the words Proyecto Maceta Inteligente (Project Smart Flowerpot).

The developers of this app explained that it allows users’ phones to communicate with an inexpensive sensor in the flowerpot, telling the owner when the plant needs watering.

“There is a commercial version of this already on the market that does the same thing,” the girls told me, “but it costs 2,000 pesos. Our app does the exact same job, but it’s inexpensive and very easy to use.”

As I learn how an app could benefit my favorite houseplant, a voice rings out: “Everyone head for the auditorium — the Pitch Event is about to start!”

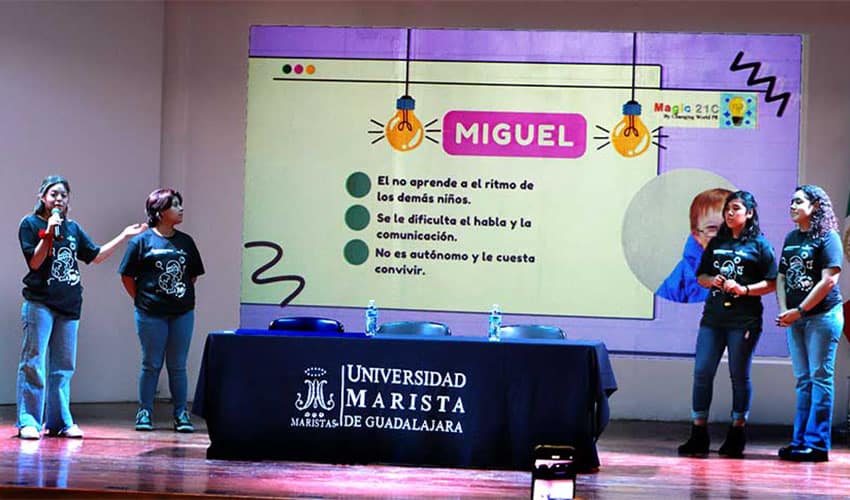

This is the part of the program that separates the wheat from the chaff. Each of the 87 teams must now get up on stage in front of a panel of jurors from tech companies like Oracle and HP. They have only four minutes to explain their apps.

The jurors’ questions are no-nonsense and can be tough: “How do you plan to finance this? What’s your competition like?”

The event I’m watching tests only participants from Jalisco, but parallel events have been held this month in Mexico City, Hermosillo, Mérida, León and Veracruz.

From here, Jalisco’s winners will compete nationally, and then the finalists from Mexico will go to San Francisco for the Technovation World Summit event in October. According to Technovation Girls, 76 percent of their program’s alumnae pursue STEM degrees.

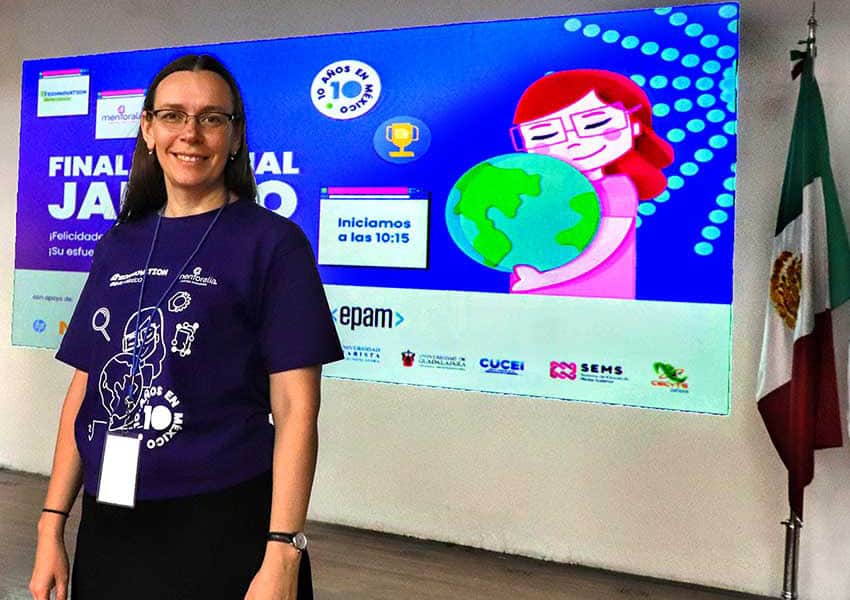

This program in Mexico is coordinated by María Makarova, who was born in Novosibirsk, Russia, and originally volunteered as a Technovation mentor in the U.S. before moving to Mexico and taking charge of the project here.

The program has been so successful in Mexico that the number of participants and volunteer mentors grew too unwieldy for one person to handle, inspiring Makarova to found a nonprofit organization called Mentoralia, which now works in the background and keeps things running smoothly.

I asked Makarova to pick out one of today’s winners and tell me her story.

“I’d like to tell you about a girl named Daniela Zoé, who is 10 years old,” she replied. “Daniela joined our program at a community center called Kokone, in an economically depressed part of greater Guadalajara called San Juan de Ocotán. Today, she won third place in the Beginners category for an app called Días del Mes, which she designed to educate girls about menstruation.”

Alexa Guadarrama, one of Daniela’s mentors, told me how Daniela came up with her idea.

“One of Daniela’s cousins had just gotten her period,” Guadarrama said. “She was 12 years old, and she had become really scared because no one had explained what was happening to her body. When we asked Daniela to think of a problem that she’d like to solve with an app, she told us this story and we helped her.

“She came up with the idea of a kind of roulette wheel. You would spin it every day, and it would give you an interesting fact about the body, or maybe an informational video that she wants to make in collaboration with a gynecologist, using non-technical terms that girls could understand.”

“The Technovation program encourages girls to study,” Makarova said. “It shows them what they are capable of and proves that they will really be able to do amazing things when they grow up. That’s my main motivation.”

The writer has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, since 1985. His most recent book is Outdoors in Western Mexico, Volume Three. More of his writing can be found on his blog.