It’s a tale nearly as old as the U.S. itself – immigrants came to the “land of the free” only to face extreme discontent. As a result, the newcomers forced their assimilation into the U.S. the only way they knew how – by turning their backs on their customs and language.

Young families insisted that children speak English in school and at home, even when parents could barely speak the language themselves. These immigrants, especially those who arrived between 1870 and 1930, no longer openly identified as Italian, Chinese, Polish or otherwise…they were American, through and through. They had to be.

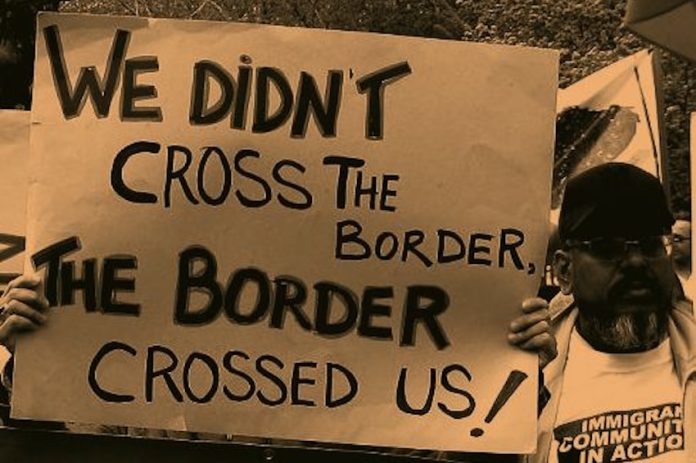

The difference with Mexicans is, well, they didn’t exactly immigrate to the U.S. At least not in the mid-19th century.

The Mexican-American War ended with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. In exchange for US$15 million, Mexico gave up about 55% of its land, which included present-day states such as California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, the majority of Arizona and Colorado, as well as parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming.

Meaning everyone who lived in these territories was effectively living in Mexico one day and the United States the next, without any say in the matter.

They would soon come to find out that they had very few rights, either.

Hostile neighbors and nearly non-existent government protection resulted in the loss of land ownership and financial stability. Many Mexicans were forced to work in low paying labor jobs to make ends meet. In just a short time, these new “Mexican Americans” found they had no representation in government, their history was largely ignored in school curriculums, and they had no feasible professional pathways. On paper, they were U.S. citizens. In reality, they were subhuman.

Key dates leading up to the Chicano Movement

Mexican Americans faced one obstacle after another. Like Blacks, they were not allowed to mingle with Whites. School, buses, water fountains and restaurants were segregated. The Civil Rights Movement started in 1945, influencing Mexican Americans to push for some critical changes.

In 1947, the Mendez v. Westminster case put a stop to segregation amongst White and Mexican schools in California.

In the early 1950s, the Community Service Organization (CSO) was created to assist in Mexican American voter registration and participation. It also helped raise money to alleviate the US$1.75 “poll tax” imposed on the most impoverished citizens of the United States, most of whom were Black, Latino, and Asian. Considering US$1.75 could buy a 100-lb sack of potatoes or beans, financial support was crucial.

As a result, in 1960, newly-elected president JFK Jr. officially recognized the powerful and ever-growing Latino voting bloc, effectively the result of the CSO’s concerted efforts.

The Hernandez v. Texas case of 1954 ruled that all nationalities, including Mexican Americans, would be guaranteed equal protection under the 14th Amendment of the Constitution as decided by the Supreme Court.

The Chicano Movement officially begins

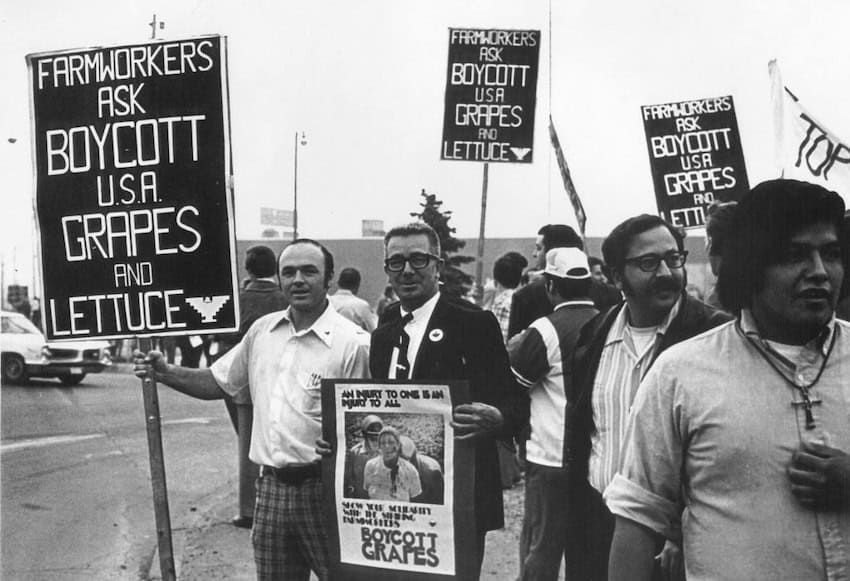

In 1965, the door to the Chicano Movement cracked wide open. A group of Filipino grape farmers in California’s central valley that made up the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) were fed up with the industry’s reliance on highly toxic chemicals and insultingly low wages. AWOC leaders approached Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez, Mexican American heads of the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), for support.

The two organizations merged to become the United Farm Workers, putting into motion a 5-year campaign against California grapes that relied heavily on a famous ad campaign: “There’s Blood on Those Grapes”. Millions of U.S. and Canadian citizens boycotted the product until the strikers won their suit. They were granted union contracts, higher pay and better working conditions.

It was a step forward.

The student walkouts of East L.A.

On Tuesday, March 5 1968, thousands of Mexican American students in the East L.A. school district hosted a walkout, demanding educational reform. They were tired of a complete lack of representation in the educational sector. No Mexican history was taught in school, students were banned from speaking Spanish and Mexican Americans were obviously portrayed in a negative light amongst historians, social scientists, and the media. What’s more, there were no college prep classes and teachers were mostly uninterested or flat-out racist.

Such a measly environment led to a high rate of dropouts and obligatory military service amongst Mexican American youth in the Vietnam War.

The Chicano Moratorium

Resulting in more protests. In 1970, over 20,000 Mexican Americans followed activist Rosalio Munoz in a peaceful protest against the war. Police officers arrived to “break it up”, which resulted in 200 arrests. Prominent LA Times journalist Ruben Salazar was killed in the scuffle, one of three to lose their lives in the tragic confrontation. This soon came to be known as the Chicano Moratorium, galvanizing even more Mexican Americans in the fight for social justice.

What were the results of the student protests during the Chicano Movement?

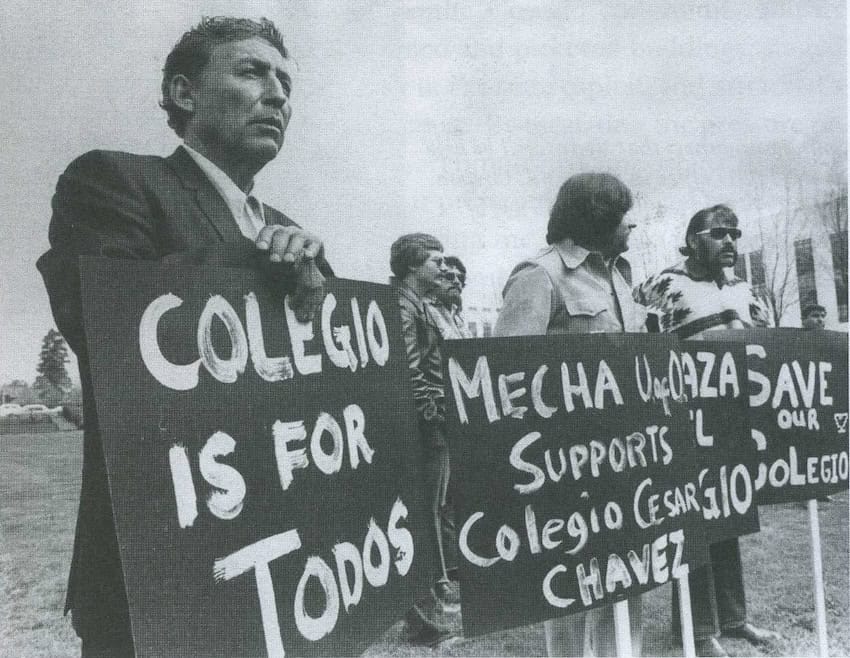

Within a few years, Mexican American students saw nationwide college enrollment increase from 2% to 25%. Study programs in Chicano history and culture were offered on campuses across the country, and more Mexican Americans were hired in upper management in the Los Angeles Unified School District.

The movement did not come without its share of failures. Some argue that the focus on ideology as opposed to cultural pride led to its eventual demise. Others say that both the movement and the term itself, Chicano, appealed more to the youth than to older generations, who identified with being Mexican.

By the mid-1970s, the movement faded. Perhaps due to the reasons mentioned above, or to the diminishment of the Civil Rights movement, or a combination of the two. Regardless of the reason, its results were long lasting. If the Chicano Movement sought to restore pride in Mexican American culture, language, and heritage, it managed to do just that. In the 2020 U.S. Census, the Mexican population reached 35.9 million, far outnumbering any other group of Hispanic descent.

Where did the word ‘Chicano’ come from?

Uncovering the true origin of the word “Chicano” is a struggle. It seems there is no cohesive explanation for the word. There are a handful of theories as to the label’s development, including:

- It comes from the Nahuatl word “Mexica” (pronounced mesheeka) the original name for Aztecs.

- It’s simply a variation of the word “Mexicano”.

- It was once a classist and racist slur against low income Mexican Americans that surged as a symbol of nationalistic pride.

What do Mexicans think of the word Chicano/a?

Because it is a term that refers specifically to Mexican Americans, I became curious about what Mexicans thought about the word. To gain a little perspective, I decided to poll my Mexican friends and followers to find out what opinion, if any, they had about the word Chicano/a.

Here is some of the feedback I received:

- I live in the U.S. but I don’t call myself a Chicana because I was born in Mexico so I am Mexican.

- It’s like burrito – a tex-mex word that we don’t use here too much.

- As if there isn’t a strong identity, but if they had to choose, they would probably see themselves more North American.

- I never loved the term because I think it conveys a touch of discrimination and segregation, but for sure there are many people who identify with it.

- It seems like now it’s an obsolete concept. I’m sure in its time it served to unify a certain Mexican community in the USA.

Are you Chicano? What do YOU think of the word? Let us know below.

Bethany Platanella is a travel planner and lifestyle writer based in Mexico City. She lives for the dopamine hit that comes directly after booking a plane ticket, exploring local markets, practicing yoga and munching on fresh tortillas. Sign up to receive her Sunday Love Letters to your inbox, peruse her blog, or follow her on Instagram.