Ask any class of seven-year-olds why the dinosaurs became extinct and a dozen voices will shout out the same answer: “It was the asteroid!” The story of a giant rock slamming into the Earth and wiping out the dinosaurs is so well-known that it often comes as a surprise to learn that the impact theory has only become universally accepted during the last couple of decades. It’s a story closely linked to Mexico, but it starts in Denmark and an area of white sea cliffs known as Stevns Klint.

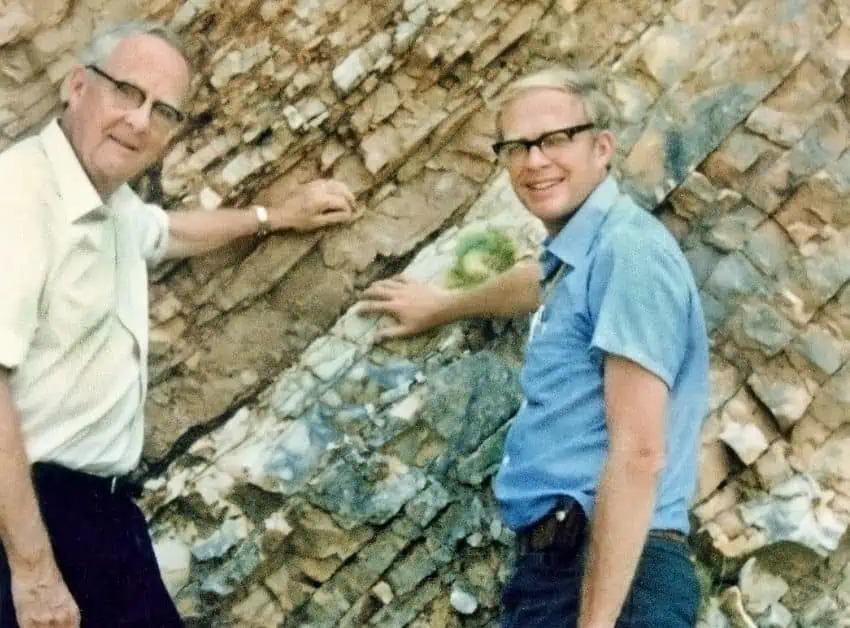

Forty years ago, American geologist Walter Alvarez was drawn to Stevns Klint by a strange geological feature: a dark, unbroken line, about 10 centimeters in width, running through the cliffs. This line is known as fish clay, and while not unique to this site, there is nowhere else on the planet where the feature is so clear and dramatic.

A mysterious line in the fossil record

Fish clay appears just above the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, a mysterious point in the geological record approximately 66 million years ago when three-quarters of life on Earth disappears. In the 1980s, it was believed that, although dramatic, this mass extinction would have occurred gradually, and there were numerous proposed causes for it, ranging from disease to climate change to a period of violent volcanic action.

If, however, as Walter Alvarez believed, the change in the fossil record was linked to this mysterious black line, that would leave two likely possibilities for the extinction: Volcanic activity remained a suspect, but Alvarez felt an asteroid strike offered a better explanation. There was a relatively easy way to find out, and an analysis of the fish clay brought an exciting result. The clay was extremely rich in iridium, an element that is exceedingly rare on Earth but abundant in asteroids and comets. The Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction, Alvarez concluded, must have been caused by an asteroid striking Earth.

In 1980, Science magazine published Alvarez’s paper, “Extraterrestrial cause of the cretaceous-tertiary extinction.” While not proving decisively that the mysterious line in the fossil record was evidence of an asteroid strike or that this strike had been the cause of the mass extinction of the dinosaurs, it opened this possibility up to more serious scientific discussion.

Since the 1960s, scientists had understood the significance of shocked quartz in identifying meteorite impact sites. Put simply, shocked quartz has undergone intense pressure, changing the rock inside. This change does not occur during volcanic action and was first observed in the aftermath of nuclear explosions. In follow-up work to his 1980 paper, Alvarez found shocked quartz crystals and other telltale signs linking the Stevns Klint fish clay to an asteroid impact.

Then, in the late 1980s, researchers in Texas published a study of a giant tsunami around the time of the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary event. While this could have been the result of an earthquake, the scale of the event pointed to something more violent. The mystery fish clay that Walter Alvarez had studied in Italy and Denmark was also found in New Zealand and the North Pacific, suggesting that whatever event produced it had been truly global.

Hunting for a crater

The argument was slowly moving toward an asteroid strike, but many scientists would not be convinced until the impact site could be identified. This was proving difficult: Earth’s atmosphere protects us from many smaller objects, while any craters that do form are usually worn away by the climate and covered over by flora. It is usually only in desert areas that craters remain relatively untouched, and a crater, even one big enough to cover the entire earth in dust, might not be easy to find after 66 million years.

Ironically, the crater had already been located. It was just that nobody had taken any notice.

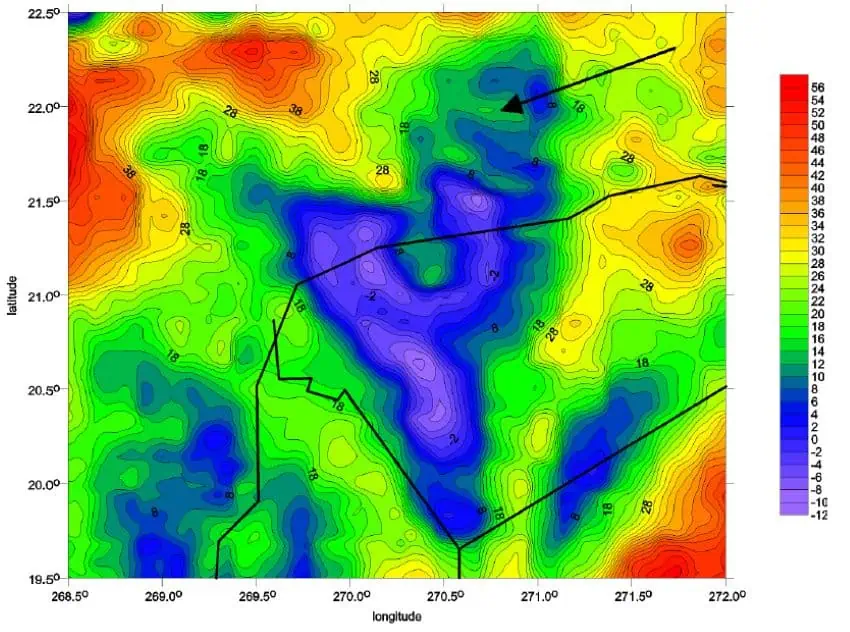

In the late 1970s, American geophysicist Glen Penfield was employed by Pemex, searching for promising oil drilling sites in the Gulf of Mexico. His team’s aerial survey identified a mysterious half-circle of magnetic disturbance, half on land — where it seemed to center on the Yucatán village of Chicxulub — and half under the sea, 120 miles in diameter.

This strange feature had already been noted but was marked on geological maps as an ancient volcano. Penfield, who had studied volcanoes at university, felt that was unlikely: He believed that the ring was an impact crater. His colleague, Yucatecan geophysicist Antonio Camargo, agreed. To their frustration, however, the core samples that Pemex had collected from the region over the years — which might contain the geological evidence to both confirm his asteroid theory and put a date to it —had been lost in a storage fire.

Despite the lack of a smoking gun to prove their hypothesis, Penfield and Camargo went ahead and presented their findings at the 1981 Society of Exploration Geophysicists conference. The result was disappointing: The conference was poorly attended, and Penfield gave his speech to a nearly empty room. There was some coverage in the press but also some critical peer reviews, and the report was forgotten for a decade.

The missing piece of the puzzle

It was the Canadian scientist Alan Hildebrand, at the time a Ph.D. student at the University of Arizona, who reopened the asteroid debate. In 1990, he traveled to Haiti, where a local professor had reported the discovery of what he believed to be the remains of a very ancient volcano. When Hildebrand and his colleagues examined the site, they found signs — including shocked quartz — that convinced the team they were seeing the debris from an asteroid strike.

The thickness of the layer of debris in Haiti suggested that this had been a major event, and that they were close to the impact point. As Hildebrand carried out his background research, he came across Penfield and Camargo’s neglected 1981 study, and the three men started to collaborate. Between them, they could put forward a convincing argument.

It was widely accepted that the Earth had undergone a traumatic extinction event around 66 million years ago. With the evidence found in Mexico and Haiti, there was now a convincing argument that a large extraterrestrial impact had occurred around the Gulf of Mexico. However, there was still no irrefutable evidence linking the Gulf crater to the mass extinction, and naysayers pointed out that the two events might have occurred millions of years apart.

The team needed those core samples from the Chicxulub crater, but drilling for new ones was way beyond any university budget. Then, in 1991, they got lucky, discovering that a few core samples had survived. This story is surrounded in mystery, but the samples had probably sat for years in a closet at the University of New Orleans. Once these surviving samples had been located, they not only yielded evidence of an asteroid strike but also allowed scientists to put a date to this event. The signs of a strike were clustered at exactly the right time: 66 million years ago, right on the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary event.

The impact theory today

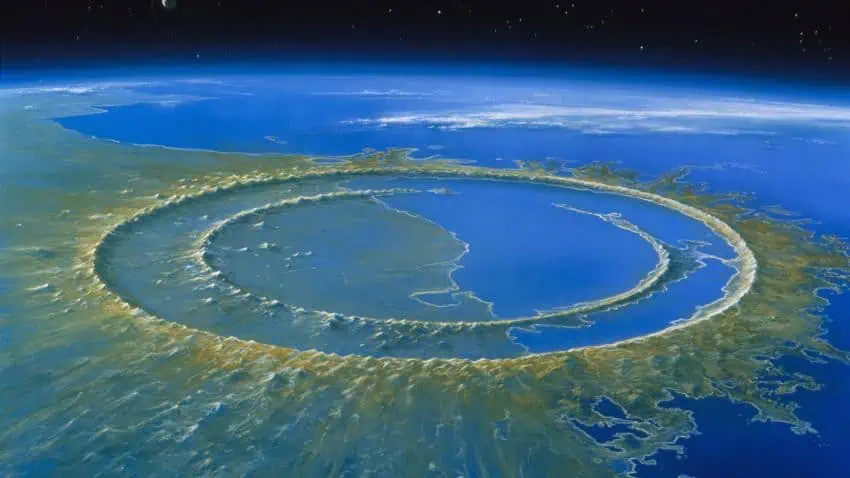

Initially controversial, Walter Alvarez’s impact hypothesis became widely accepted and known over the following decades. In March of 2010, Science brought together an international panel of experts in geology, paleontology and related fields. The scientists reviewed decades of scientific literature and reached a consensus: The extinction event of 66 million years ago had been sudden and violent, and volcanoes were not to blame. As any seven-year-old can tell us today, the dinosaurs had been doomed by a large object hurtling in from outer space and striking the shallow waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Scientific attention returned to the Chicxulub crater in 2016, when money was found for a drilling expedition. Working off the coast of the Yucatán Peninsula, the team extracted core samples from ground zero, bringing up rocks from 670 meters beneath the seafloor. As scientists studied this new resource, a clearer picture of that day began to emerge. The major finding has been that the impact deformed the surrounding rocks, making them more porous and less dense, creating a nutrient-rich home for simple organisms. The ironic result was that the center of the devastation quickly became a sanctuary for microbes and plankton. This might have important implications for finding life on other planets and moons, where similar impacts have been observed.

There have also been developments in identifying the nature of the asteroid. A study analyzing the chemical signatures of rocks from the end of the Cretaceous period suggests that the Chicxulub asteroid was a carbonaceous chondrite, a class of meteorite that formed billions of years ago in the early solar system and now found in deep space, far beyond Jupiter. No doubt other discoveries await us in the years ahead as we continue to build our picture of the day death and destruction came to the shores of ancient Mexico.

The tiny town of Chicxulub Pueblo has been identified as being at the center of the ancient impact site. There is little to see and the village of 4,000 people attracts few tourists, but tourism related to the Chicxulub impact does exist in the region. The ring of cenotes, or natural sinkholes in limestone bedrock, which can be found all over the Yucatán Peninsula are popular with tourists and may have been created by the impact, though this is debated. The Chicxulub Science Museum is close to Mérida and has exhibit halls on the Solar System, the Chicxulub impact and mass extinctions. The Museo del Meteorito, dedicated specifically to the impact, opened in Progreso in 2022, with museography by the director of Coahuila’s acclaimed Museo del Desierto.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.