I’ve taken many bus trips from Puebla to Oaxaca. It’s a beautiful ride — winding through gorgeous mountains sometimes covered with cactus, other times with pine trees, its valleys far below seeming to stretch out forever. But until I drove there, I really didn’t really appreciate its beauty — or the amazing number of near-death experiences you can have on that trip.

After years of swearing I wouldn’t drive in Mexico — ever — we bought a car: “we,” as in, mi novia Martha and I. Until now, Martha had done all the driving, and I was more than happy to let her.

I’ve written about the challenges faced when driving in Mexico, and nothing and nobody could persuade me to get behind the wheel when the phrase “rules of the road” is an oxymoron. But we scheduled a trip to Oaxaca and decided to drive.

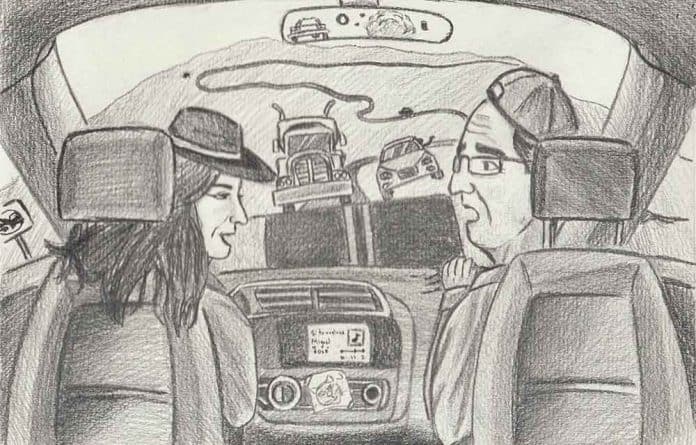

I told Martha I’d share the driving. I figured she could take the wheel in the cities and I’d take it on the highway. A highway’s gotta be less chaotic, I thought. It’s gotta be safer.

As they say, ignorance is bliss.

In the United States, there are rules that drivers, for the most part, obey. Like, if there’s a solid double yellow line on a road, it means it isn’t safe to pass. On that highway to Oaxaca, thoughtful officials had not only painted solid double lines in the areas where it’s not safe to pass, they had also included a sign showing two cars side-by-side with a slash mark through it. This should obviously be read as “Do not pass.” These warnings were in areas, for example, where there was a sharp curve that you couldn’t see around.

Why they wasted money on paint and signs is beyond me. Nobody pays the slightest attention. The only reason I can figure for why they exist is that someone’s brother-in-law holds the contract for painting those double lines. The more double lines, the more paint used, and the more money the family earns.

Another family member probably makes the signs.

So, people pass in Mexico when there are solid double lines on the road. All the time. Doesn’t matter if it’s a blind curve. Doesn’t matter if they’re going uphill on a blind curve. Caution be damned. They’re gonna pass.

It’s especially thrilling when there’s a car coming right at you. And here’s where whoever designed that road in Oaxaca showed that they knew something about Mexican drivers: in the mountains, the highway really isn’t one lane in each direction. It’s more like one and a half.

That half lane is what people in the U.S. would call a service lane or a breakdown lane. Surprisingly, and happily, drivers on that highway to Oaxaca tend to be grateful, and they make good use of the half lane, because they know that if they don’t, there’s gonna be a need for body bags.

Many drivers will decide to pass around the car in front of them — whether or not it’s a legal passing zone and whether or not they’re heading straight for a car coming in the opposite direction on the other side of the road.

When a driver sees the oncoming car, most of the time, they’ll simply squeeze over into that service lane. The driver straddles both sides of the road, and everyone survives and continues on their journey.

It usually works but there are a frightening number of accident shrines dotting the highway.

Now, there are sections where there’s a broken, single line, which indicates it’s safe to pass. These are in the rare straight stretches on that highway. Again, in the U.S., when it’s safe to pass, people tend to wait until there are no cars approaching in the opposite lane and then accelerate and pass. When someone wanted to pass on that highway, they simply pulled out, even with a car hurtling at them a short distance away.

I’m happy to say that I drove part of the way to and from Oaxaca and survived. And, yes, I’ll admit I did the things that all the other drivers were doing: I passed when there was a solid double line; I passed when there was a car coming towards me in the opposite lane.

I like to think that I drove at least a little more cautiously than most. I certainly drove more cautiously than Martha, who kept the pedal to the metal (I know we pulled some serious g’s on a few curves) and passed cars and trucks with an unsettling gleam in her eye.

I’ve always said that driving in Mexico is like a video game — OK, a video game with possible dire consequences — and that trip proved it.

Although my nerves got a workout and I probably had a few months shaved off my life expectancy, I have to admit that I appreciated the beauty more because I figured I was going to die.

Nothing sharpens the senses like coming face-to-face with one’s mortality.

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.