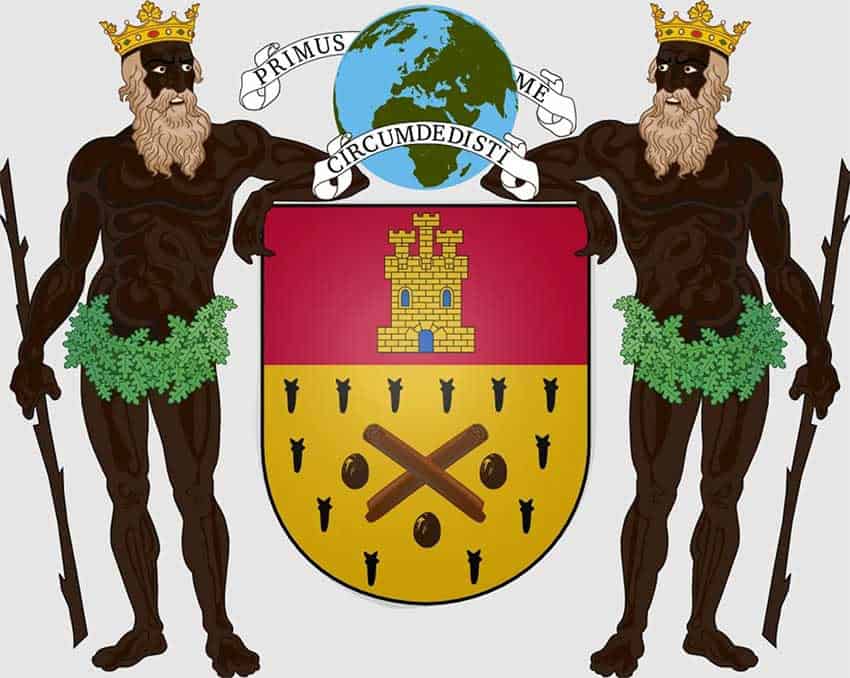

The opening gong for the age of international trade was struck in 1522 when Juan Sebastián Elcano succeeded in sailing around the world. Elcano’s coat of arms bears a talking globe which says, in Latin, “you were the first to encircle me.”

Elcano’s achievement encouraged Spanish navigators to try to reach the Far East starting from Mexico’s Pacific coast.

The birth of the Far East trade

On November 21, 1564, a convoy of boats sailed from the port of Barra de Navidad, Jalisco, with the aim of reaching the Philippines, and then somehow finding their way back, a serious challenge due to unfavorable winds.

“Five boats started out from Barra de Navidad,” says Guadalajara’s award-winning historian, Padre Tomás de Hijar Ornelas, “but the first one of them to make it to the Philippines and back was a patache, a little sailboat named the San Lucas, piloted by Alonso de Arrellano. The San Lucas got separated from the convoy but made it to the Philippines, discovered several islands and then sailed back to Mexico, following a route plotted by Andrés de Urdaneta, which involved sailing northeast from Manila to Japan to catch the favorable Westerlies that brought the San Lucas to the shores of northern California, after which it followed the coast back down to Barra de Navidad.

The grueling voyage

For the next 250 years, the Manila galleon followed this route, making a round trip from Acapulco once a year. The grueling return typically lasted five or six months, and dozens of crew members would succumb to scurvy, dehydration, starvation or heat stroke.

Despite all this, the tornaviaje, as it was soon called, proved very profitable.

America was now linked, by trade, both to Europe and to the Far East. Globalization had become a reality.

Silver, vanilla and cacao for China

“The Manila Galleon was more popularly known as the Nao de China,” de Hijar told me. “From the new world it carried silver coins minted in Mexico City — it was the first dollar in the world! Then there was vanilla, cacao, tobacco and cochineal (carmine dye), which is made from insects found on the pads of prickly pear cacti.

“One more important item was henequen. In seawater, the fibers would last ten times longer than hemp. So, henequen rope was invaluable for marine use. Believe me, if you were a Malay pirate, you had to have rigging made of henequen!”

Silk and spices to Mexico

To Mexico, the Nao de China brought the most prized goods of the Far East: silk, spices, porcelain, carved ivory and Asian lacquerware.

As far as spices go, a cursory examination of dishes popular in Guadalajara shows how radically Mexican cuisine was influenced by contact with the Far East.

Birria, mole and ponche

Birria, for example, is a rich, spiced meat stew that originated in Jalisco. While its base is Mexican, it includes:

- Cinnamon – From Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), it adds a sweet-spicy undertone.

- Cloves – Native to Indonesia and used in the marinade for their pungency.

- Black Pepper – Now ubiquitous, it originated in India and is common in the spice rub.

- Cumin – Though often associated with Middle Eastern cuisine, it was traded through Asia and adds earthy warmth.

Mole is a very Mexican sauce made with several spices that trace their origins to Asia. Like birria, it contains cloves, black pepper and cinnamon. Some regional variations also use star anise (from South China), which adds licorice-like sweetness.

Ponche, Christmas punch, is as Mexican as can be, but again borrows from Asian spice traditions. In it, you’ll find cloves, which give it spicy warmth, and Ceylon cinnamon sticks. For tang, ponche has tamarind, now very popular in Mexico, but originally from tropical Africa and widely cultivated in India and Southeast Asia. Sometimes Mexicans add ginger to their ponche to give it a zesty kick. Ginger started out in Southern China and eventually spread all over Asia.

Guadalajara, the cultural sponge

The galleon created a culinary mestizaje — a fusion of Asian, indigenous and Spanish traditions that still flavors Mexican cuisine today.

Guadalajara became a cultural sponge, absorbing Asian aesthetics and flavors and blending them into its own vibrant identity. The great galleon — which could carry up to 2,000 tons of cargo plus a crew of over 400 — brought not only goods, but ideas and technology. It brought new techniques for weaving, for making lacquer and ceramics, for navigation, and for printing with woodblocks.

From coconut spirit to tequila

One example of a technique that revolutionized Mexico was the introduction of the Filipino alambique (still) to the Pacific coast of Colima to turn the fermented sweet sap of the coconut palm (tubâ) into a liquor known as lambanóg (palm spirit). This was so successful that the Spanish crown ordered all the coconut palms cut down.

Instead of buying Spanish brandy, the Colima Filipinos applied their alambiques to distilling the sweet juice of cooked agave fibers, giving birth to mezcal and tequila.

Note that neither Filipinos nor coconuts are native to Mexico, and probably reached Colima when the Manila galleon stopped off in Manzanillo.

“How did Guadalajara become a global city?” I asked de Hijar, when the destination of the Manila Galleon was Acapulco?”

Global, thanks to contraband

“In a word: contraband,” replied the padre. “Most of the cargo was bought and paid for in advance and ended up in Mexico City, but before reaching Acapulco, the Nao de China would stop off in San Blas and Manzanillo, where the crew did wonderful business. And from both of these ports there was a Camino Real, leading, of course, to the capital of New Galicia, Guadalajara.”

So, when you are next in Guadalajara and are served a very Mexican café con canela for breakfast, please note that the café came from Ethiopia and the canela from Ceylon. Welcome to the global city!

John Pint has lived near Guadalajara, Jalisco, for more than 30 years and is the author of “A Guide to West Mexico’s Guachimontones and Surrounding Area” and co-author of “Outdoors in Western Mexico.” More of his writing can be found on his website.