A recently published study has unveiled the true nature of Guiengola, a sprawling Zapotec enclave in the southern part of Oaxaca state that was abandoned shortly before the Spanish conquest in 1521.

For years, the area in the jungle was believed to have been simply a fortress for housing soldiers. In fact, it was a thriving, expanding and fortified city whose residents relocated to nearby Tehuantepec, where their descendants still live.

These findings — brought to light this week in Discover, Newsweek and other publications — come from Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis, a postdoctoral researcher at McGill University in Montreal whose mother’s family is from Tehuantepec, a municipality of 67,000 about 20 kilometers from the archeological site.

“I remember them talking about [Guiengola] when I was a child,” Ramón Celis told Newsweek. “It was one of the reasons that I chose to go into archaeology.”

In November, a study based on his and his team’s research over five-plus years was published in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica. In part, it illustrates the political and social workings of the Zapotec civilization, which met its end at the hands of Spanish conquistadors in the early 1500s.

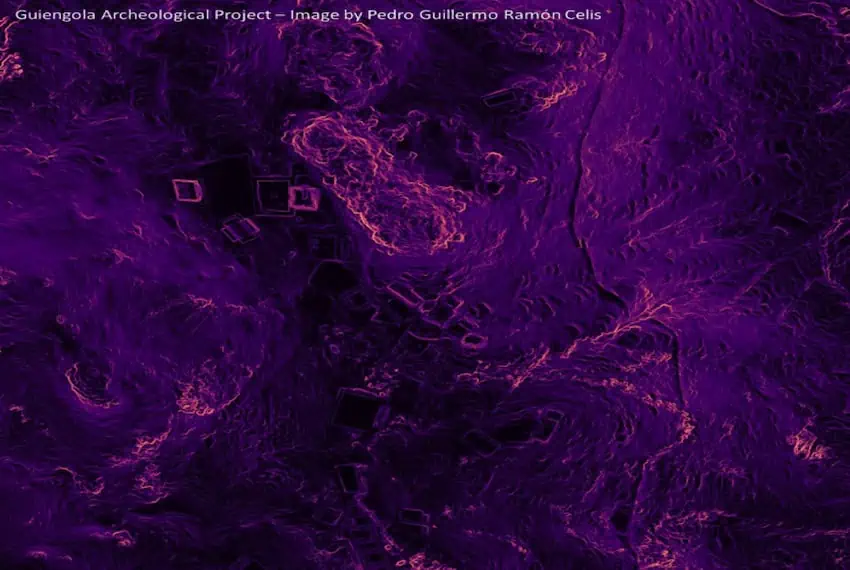

Using airborne LiDAR technology, Ramón Celis and his team scanned and mapped the site, revealing that Guiengola spanned 360 hectares and contained more than 1,100 buildings, including temples and ball courts. It also had a network of roads and was fortified with 4 kilometers of walls.

LiDAR stands for Light Detection and Ranging; it’s akin to a light-based version of sonar, using pulses of laser beams to produce detailed topographic maps of the terrain.

“Because the city is only between 500 and 600 years old, it is amazingly well preserved,” Ramón Celis said. “You can walk there in the jungle and still see standing houses, doors, hallways and fences.”

Guiengola is located on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec — the narrowest strip of land in Mexico between the Gulf of Mexico and the Pacific Ocean.

Today, the area is an emerging trade corridor that includes a 303-km, interoceanic railway that can haul shipping cargo between ports on opposite coasts more efficiently, some say, than the Panama Canal.

My article on the analysis of the urban layout of Guiengola was just published in @AMesoamerica its open access so check it out! #lidar #mesoamerica #archeology https://t.co/OCs7m5HOTV pic.twitter.com/fx9MNJcwXw

— Guillermo Ramón Celis (@arqlgoGuillermo) November 8, 2024

Ramón Celis contends that Guiengola’s layout indicates a hierarchically organized city, with a clear division between elite and commoner neighborhoods. The LiDAR scans, which were conducted from 2018 to 2023, show elite structures such as temples and ball courts clustered in specific areas, with other areas of residential structures.

“The site was mischaracterized for years,” Ramón Celis said. “Our findings show that it was a sophisticated city with a structured political and social system.”

The study’s findings, Ramón Celis added, contribute to a broader understanding of Zapotec governance and urban planning, as well as their interactions with the Spanish during the early colonial period.

Ongoing research is planned, with scholars hoping to gain further insights on the resilience and complexity of pre-Columbian civilizations in Mesoamerica. For those who aren’t archaeologists or anthropologists, perhaps a visit to the Museum of the Cultures of Oaxaca in the city of Oaxaca would be in order.

Meanwhile, Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has a web page about visiting Guiengola that still includes: “It is believed to have been a fortress for defense against hostile groups.”

Visitors to the mostly undeveloped site can explore houses, plazas, tombs, pyramids and other structures; it’s open from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. daily and is free. Although a visitor might run into a local guide who can give a tour, INAH “does not have any type of services or infrastructure to receive tourist visits” beyond a custodial staff.

Details about reaching the site — including driving up a dirt road to a small parking area, then hiking 45 minutes through a cactus forest — can be found via iOverlander.com. The dirt road is about a 45-minute drive from the port city of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, one terminus of the Interoceanic Railroad.