I’ve visited several museums in Mexico, but none are located in a more beautiful building than the Museum of the Cultures of Oaxaca (Museo de las Culturas de Oaxaca) in Oaxaca city.

The museum is housed in the former convent of the Church of Santo Domingo de Guzmán, which was built in the 16th and 17th centuries. A classic Mexican baroque building, it’ll make you feel like you’re back in the colonial era.

The former convent, converted into a museum in 1972, has a collection occupying 14 rooms spread across the building’s three floors. It’s a great source for learning about the state’s history, from its earliest settlement up through the modern era.

The “Ancient Cultures” hall (Culturas Milenarias) contains pieces from the first human settlements in Oaxaca. These objects showcase ancient artisans’ astonishing technical skills and the belief systems of the region’s various civilizations.

The second hall, called Tiempos de Florecer (Times of Flourishing), covers the Classic Period, between A.D. 200 and 900, with much of the focus on figures from Monte Albán, the ancient mountaintop capital of the Zapotec civilization. In this era, the Zapotecs, who occupied much of the Central Valleys of Oaxaca, achieved their peak artistic expression and developed a calendar and a system of writing.

Artifacts that were found in Monte Albán’s Tomb 7 fill an entire room in the museum, and they’re nothing short of stunning. You’ll find these items, unearthed by archaeologist Alfonso Caso in 1932, in Hall III, “The Treasures of Tomb 7.”

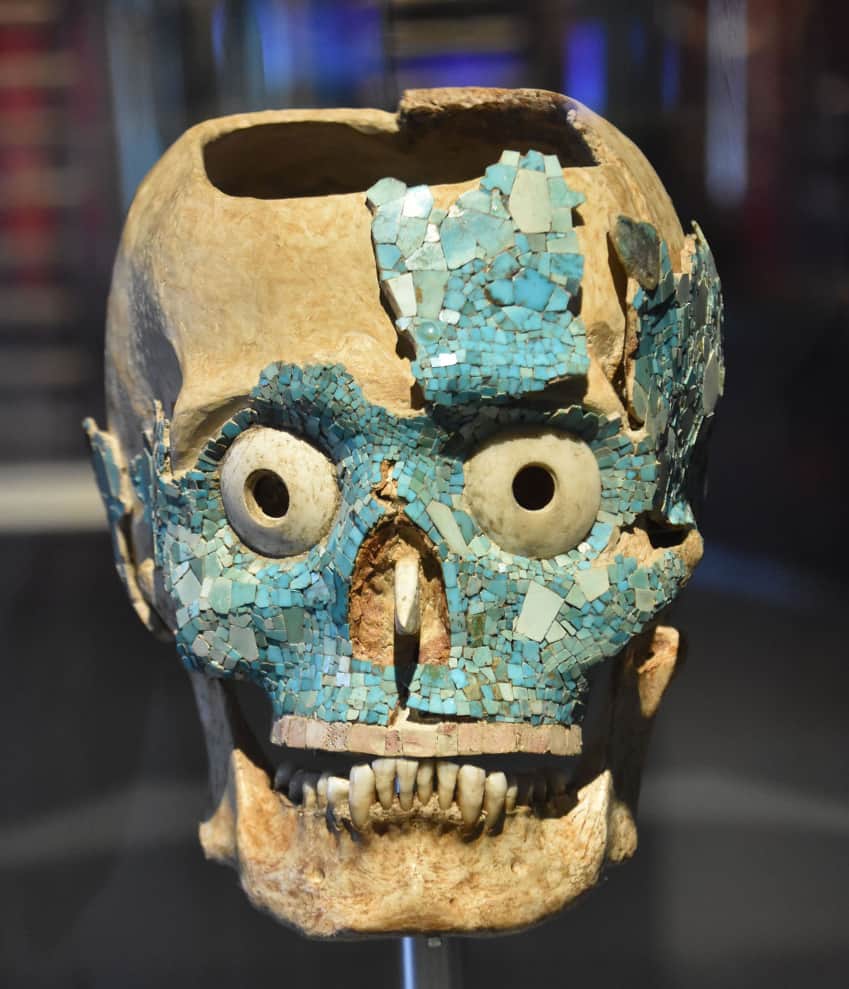

Tomb 7 was one of the richest Mesoamerican burial sites ever discovered, containing around 600 pieces made of a variety of precious and semiprecious materials, including gold, turquoise, silver and amber. Although Monte Albán was originally a Zapotec city, the inhabitants abandoned it around A.D. 900. It was subsequently occupied by Mixtecs, who reused the site’s structures, including the tombs.

Tomb 7 is believed to date from about A.D. 1330. It contained the remains of Mixtec rulers or royalty. While its gold pieces and turquoise skull attract most of the attention, Hall III also hosts a display case containing bones with carvings so small and intricate as to defy belief. The carvings refer to events during the Mixtec dynasty.

Other rooms in the museum display artifacts from other ancient sites that arose after Monte Albán’s collapse in A.D. 900, including that of Yagul, Mitla and Zaachila; the ruins of all three are within driving distance of Oaxaca city.

Hall VII is dedicated to the Spanish conquest, and subsequent rooms to the introduction of Catholicism in Mexico and the emergence of a hybrid Indigenous-Spanish culture and Spanish and modern Oaxacan arts.

The museum also contains an exhibit about the rebozo, the cloth traditionally used across Mexico to carry babies. There’s also an exhibit dedicated to depictions of the Xoloitzcuintli, the hairless dog believed to guide the spirits of the dead through the underworld. The first floor also contains the impressive Francisco de Burgoa Library and a gift shop.

The building is so large, it seems to go on forever. Plan on a couple of hours to tour the museum, but note that viewing all the rooms in one day isn’t easy. Better to cover fewer rooms or take two days to see them all.

Be sure to look up and around as you wander through the rooms. There are faded murals on walls, carvings of saints and virgins on the ceilings and golden altarpieces and impressive doorways. There’s also a great view of the site’s botanical garden from the upper floors and another of the Church of Santo Domingo.

The museum is open Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Admission is 90 pesos (US $5)

Joseph Sorrentino, a writer, photographer and author of the book San Gregorio Atlapulco: Cosmvisiones and of Stinky Island Tales: Some Stories from an Italian-American Childhood, is a regular contributor to Mexico News Daily. More examples of his photographs and links to other articles may be found at www.sorrentinophotography.com He currently lives in Chipilo, Puebla.