The history of Mexico has many stories about the heroes and events of the Mexican Revolution but one military leader was, until recently, rarely mentioned: the transgender soldier Colonel Amelio Robles — whose gender identity was not generally a known fact for much of Mexico’s history but was known by the Mexican Army.

Robles lived his life as a man from the age of 24 until his death at the age of 95. Shortly before his death, he was finally recognized for his service to the country and decorated as a hero of the Mexican Revolution.

His story became better known in 2022 with the publication of Ignacio Casas’ novel, “Amelio, Mi Coronel.” (Amelio, My Colonel).

“Robles was a very complex person,” Casas states. “In order to understand him, you have to look at his life in three phases — his youth, the Mexican Revolution years, and the post-revolution years.”

Amelio was born Malaquías Amelia de Jesús Robles Ávila in 1889 in Xochipala, Guerrero to Casimiro Robles and Josefa Ávila. The youngest of three children, Robles was from the country but not poor — Casimiro was a well-to-do rancher and owned a mezcal distillery. Robles received a Catholic education from the Society of the Daughters of Mary of the Miraculous Medal, a congregation dedicated to the spiritual formation of young girls.

Robles was raised learning how to sew, cook and iron, but preferred riding horses, lassoing cattle and practicing marksmanship. After Casimiro died, Robles

In 1912, at the age of 23, Robles joined Emiliano Zapata’s army, not because of revolutionary beliefs but because it offered freedom from conservative rural society.

The war was forever life-changing for Robles, whom fellow soldiers initially called “La Güera Amelia.” However, Robles began to dress in typical male attire of the time, took the name Amelio and insisted — often at gunpoint — at being referred to by others as male, according to a history of Robles written by the Ministry of Culture.

Robles rose quickly through the ranks, attaining the rank of colonel. In his personal logs, he listed participation in 70 battles — gaining the respect of fellow revolutionaries with his prowess as a military leader — commanding up to 1,000 soldiers. He was a skilled horseman, an excellent marksman and a fearless soldier.

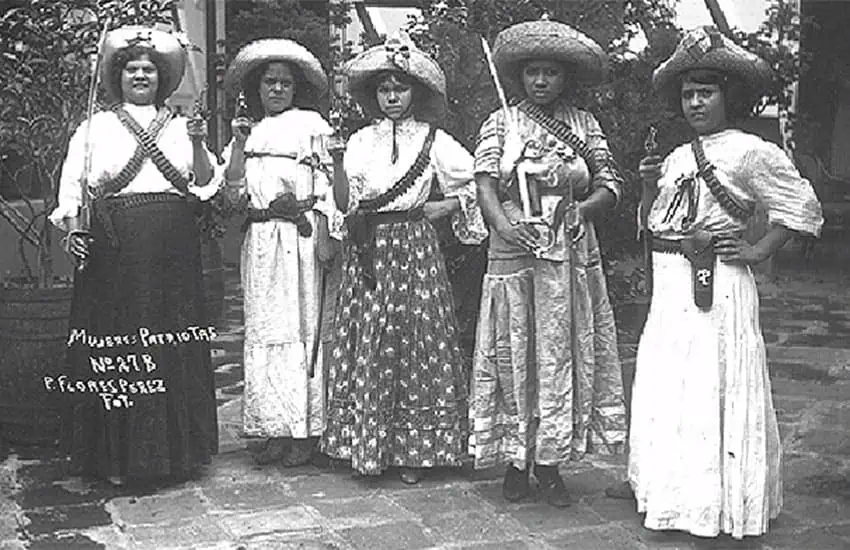

There were also numerous examples of women who fought in the revolution alongside male soldiers, and some wore men’s clothing and took male names. Petra Herrera, credited with seizing Torreón as a Villista soldier in 1914, was known as Pedro Herrera. Ángela Jiménez, who fought with the Zapatistas and Villistas, became Ángel Jiménez.

Robles embraced his gender identity until his death in 1984 at the age of 95. In the 1950s, he even managed to alter records to reflect it.

After the military phase of the revolution ended in 1920, Robles supported revolutionary general Álvaro Obregón, who became president (1920–1924). He took up arms and fought with Obregón forces in the Agua Prieta Revolt, which brought an end to the government of Venustiano Carranza.

He then settled in Iguala for a time afterwards but was attacked by a group of men attempting to disrobe him so as to “prove” him to be a woman. Robles killed two men in self-defense and was incarcerated for a second time, confined to the women’s area of the jail.

In the 1930s, Robles met Ángela Torres and married, settling into civilian life and later adopting a daughter, Regula Robles Torres. He remained politically active, joining the Socialist Party of Guerrero and the League of Agrarian Communities. But he still had not received the recognition he deserved as a revolutionary leader.

Robles was determined to get that recognition. In 1948, he finally received the medical certificate required to officially enter the Confederation of Veterans of the Revolution — confirming that he had taken six bullet wounds in battle.

In 1955, he also began the process of changing his service files to identify him as Amelio Robles rather than his prior name; he even had a false birth certificate inserted into his personal files at Mexico’s military archives.

According to historian Gabriela Cano, “The [false] document attests to the birth of the child Amelio Malaquías Robles Ávila. Except for the baby’s name and sex, all other data coincides with the original birth certificate from the Zumpango del Río civil registry book.”

Robles was in his 80s when the Ministry of National Defense finally recognized him as a veteran of the Mexican Revolution. Shortly thereafter, he received the Legionnaire of Honor of the Mexican Army distinction and the Medal of Revolutionary Merit.

Before his death, he was recognized by three former presidents — Adolfo López Mateos, Manuel Ávila Camacho and Luis Echeverría — as an outstanding revolutionary.

But for all his attempts to change his identity records, some still refused to accept him as male: his childhood home became the Coronela Amelia Robles Museum.

Perhaps as a sign that Mexico is changing — becoming more tolerant and supportive of gender diversity — the Culture Ministry’s website states that “the participation in the [Mexican] Revolution [of Amelio Robles] as a transgender man whose identity was recognized and who was a colonel marks a milestone. And contrary to what is commonly thought, it indicates that people of gender diversity have always been present and have participated in many historical events of the country.”

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.