I had already written the second part of my piece on Frida Kahlo. But after reading the feedback I received from part one — and listening to the opinions of friends, family and acquaintances —I felt compelled to reconsider it.

My professors used to warn us to approach studies of movements and artists with caution. Critics and historians, they said, inevitably project their own preferences and phobias onto the page. Kahlo is a perfect example: scholars, writers and the general public have turned her into a mirror, reflecting their own context and visions of life.

For many, the first encounter with her work provokes discomfort — sometimes even revulsion — for its raw intimacy. Yet for countless communities, Kahlo has become a powerful emblem, one that propelled her to a level of cultural celebrity few visual artists have ever achieved. “Fridamania” — the cult of personality and commercial obsession surrounding her — was born in the 1980s and thrives to this day.

Frida in her time

During her lifetime, Kahlo was already a notable cultural figure in Mexico. But she was almost always introduced as “the wife of Diego Rivera.”

Rivera was the towering figure of Mexican modern art. Alongside David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco — Los Tres Grandes — he redefined Mexican national identity through monumental murals that celebrated revolutionary values and Indigenous heritage.

While other movements existed in early 20th-century Mexico, none enjoyed the state sponsorship that muralism did. Its influence remains embedded in Mexican cultural discourse even now, a romanticized vision of pre-Columbian civilization that doubled as one of the most successful cultural propaganda projects of the 20th century.

Kahlo’s contribution was radically different. She turned inward, confronting the private sphere with startling candor: domestic life, pain, miscarriage, infertility, desire, identity. She lived — and loved — with radical openness, defying the social conventions of her time.

After Frida

Diego Rivera, beyond being a gifted painter, was an extraordinary promoter — especially of Kahlo’s work. He frequently called her the greatest Mexican painter of them all. Following her death in 1954, he established a trust that transformed the Casa Azul into a museum, which opened to the public in 1958. This act preserved her possessions and paintings, allowing researchers and admirers to piece together the mythology that now surrounds her.

Dolores Olmedo, a close friend and patron, became one of the foremost collectors of Rivera’s and Kahlo’s art. Her namesake museum in Mexico City, inaugurated in 1994, further solidified their place in the cultural canon.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, a generation of artists began revisiting Mexican icons — Zapata, the charro, and Kahlo herself — subverting them into symbols of feminism, queer identity, and cultural resistance. By the century’s end, Kahlo had become a vessel for causes she may never have imagined.

Frida goes global

In 1982, the Whitechapel Gallery in London mounted the first major Kahlo retrospective outside Mexico, pairing her with photographer Tina Modotti. The show sought to challenge the Western-centric canon and give overdue recognition to women artists. The academic and curatorial world, eager to correct historical exclusions, began folding Kahlo into broader conversations about race, gender and global modernism.

A year later, Hayden Herrera published “Frida: A Biography of Frida Kahlo,” a landmark study that cemented Kahlo’s mythos. Though Herrera’s psychoanalytic interpretations at times verge on speculation, the narrative she shaped — Kahlo as wounded, passionate, political, queer martyr — remains dominant in the zeitgeist.

From that moment forward, exhibitions, documentaries, films, and books multiplied, feeding the global appetite for all things Frida from different perspectives. In one decade, Frida became an icon for multiple communities.

Feminist Frida?

Kahlo never called herself a feminist — because feminism, as we understand it, barely existed in her Mexico. Most women were confined to the home, excluded from voting, banking, and public debate. Cultural life was open to them, but their work was treated as “secondary” art.

Still, her subject matter has invited feminist readings. While the muralists painted sweeping political epics, Kahlo painted the intimate: the home, the body, the psychic pain of miscarriage, the betrayals of love. In today’s language, she articulated a “female gaze.”

Yet Kahlo did not speak of shattering glass ceilings or fighting for gender parity. Her life remained bound, in many ways, to Diego Rivera’s orbit. She was not an iconoclast in the way modern feminism would define one.

And yet, she opened doors — alongside contemporaries like Modotti, Nahui Ollin, Lola Cueto, Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, Adela Siqueiros, Lilia Carrillo, María Izquierdo, Rosario Castellanos and Elena Garro — for women in Mexican culture.

Queer Frida and sexual politics

A professor once told me that Mexico has always had space for homosexuality — so long as it stayed discreet. Novels like “Queer” and “Junky” by William S. Burroughs offer a glimpse into that discreet freedom.

Many authors have psychoanalyzed Kahlo’s sexuality, and suggest that her openness was a reaction to Diego’s infidelities. Yet, her bisexuality is well-documented, predating her marriage to Rivera. After his first infidelity, their relationship evolved into an open marriage. Rivera himself bragged about her affairs with women.

Later scholars, in the 1980s and ’90s, reframed this arrangement as a defiant challenge to patriarchy and heteronormativity. It’s my bold assessment to think that she wasn’t trying to subvert the Mexican machista society, but to be provocative with her husband and lovers. In that artistic context, Kahlo was not necessarily the most transgressive figure of her era — lesser-known Mexican artists like Nahui Olin or Nellie Campobello pushed even further.

A Mexican icon

Kahlo, like many of her contemporaries, was steeped in European culture even as she came of age during Mexico’s nationalist renaissance. Her signature Tehuana dress was not an act of cultural appropriation but a political one: a declaration of allegiance to Mexico’s Indigenous heritage and rejection of foreign domination.

Through today’s lens, that sort of nationalism can look romanticized — an embrace of Indigenous symbols without grappling with the realities of Indigenous marginalization, but by the 1990s, Kahlo’s image had been reinterpreted: in Mexico, she became a feminist counterweight to the macho charro; abroad, she was fetishized as folkloric, colorful, “authentically Mexican.”

Frida as a pop culture icon

There is no faster way to neutralize a countercultural figure than to turn them into a commodity. Movements and figures that once stood for resistance become popular and fashionable statements. You can now find t-shirts of The Clash, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Janis Joplin, Nirvana and Frida Kahlo sold at low cost, fast fashion outlets like T.J. Maxx and Primark.

Perhaps unexpectedly, it was Madonna who played a pivotal role in Kahlo’s pop-culture ascent. In the 1980s, she is rumored to have paid US $1 million for “Self-Portrait with Monkey,” the first of five Kahlo paintings she would collect.

Madonna introduced Kahlo’s work to designers like Jean Paul Gaultier, whose 1998 collection was inspired by Kahlo’s aesthetics and Marilyn Manson’s pastiche of gothic and glam styles. The iconic outfit he designed for Milla Jovovich in “The Fifth Element” was inspired by “The Broken Column.” Karl Lagerfeld followed suit, styling supermodel Claudia Schiffer as Frida for a Vogue Germany editorial. Patti Smith, Salma Hayek, Coldplay, Gwen Stefani, and Dolce & Gabbana have all drawn inspiration from her image.

The market value of her art

Determining the value of an artwork is a complex, multifactorial process shaped by cultural relevance, rarity, and the opinions of tastemakers — critics, curators, galleries and institutions.

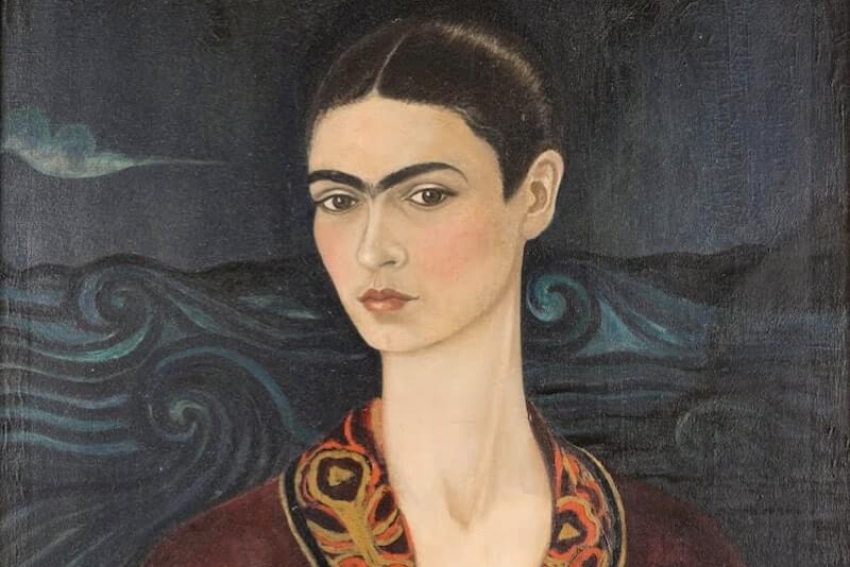

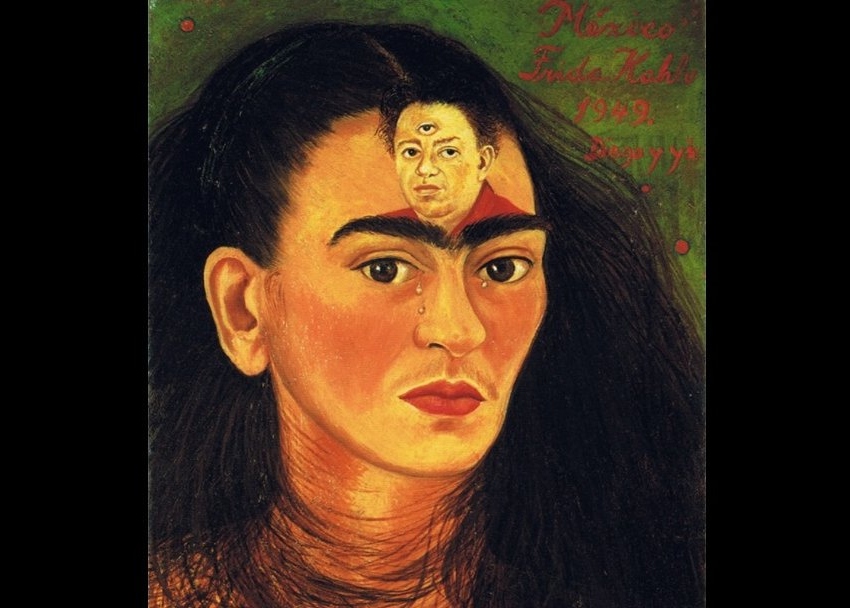

In 1979, a Kahlo painting sold for US $85,000. By 2021, her 1949 “Diego y yo” fetched $34.9 million at auction, making her the most expensive Latin American artist in history. As Fridamania continues to grow, she’ll likely break her own record again.

The Frida Kahlo Corporation

Frida’s image — unibrow, braids, flowers — has been reduced to an aesthetic. Her face now adorns every imaginable product: notebooks, mugs, socks, tequila bottles.

Whether this constitutes cultural trivialization or widespread homage is debatable. What is clear is her global relevance.

In 2005, Venezuelan entrepreneur Carlos Dorado acquired the commercial rights to Kahlo’s name and likeness from her niece, Isolda Pinedo Kahlo, creating the Frida Kahlo Corporation. Any officially licensed product now generates revenue for the company.

The legacy of Frida Kahlo

I often wonder what Kahlo would have made of all this.

In my admittedly subjective imagination, she would have delighted in her ubiquity but recoiled at her own commodification. Her communist sympathies would have resisted the idea of becoming a brand. And yet, she might have embraced the causes — feminism, queer liberation, Indigenous pride — that now rally beneath her image. Just as she once embraced the red flag of communist revolution.

What do you think? What would Frida make of the world’s obsession with her? I’m listening.

María Meléndez is a Mexico City food blogger and influencer.