Growing up as the daughter of an actor, my house shelves overflowed with volumes

explaining how drama evolved across civilizations. Hidden among those heavy tomes

was a small, humble book titled “Teatro Mexicano.” It began with a simple, startling claim:

The earliest form of Mexican theater was the Catholic pastorela, created as a dogmatic

tool.

Years later, while studying the Spanish Conquest in college as a cultural collision, these

same pastorelas — and their sister celebration, the posadas —became my focus, since

they were more than dogmatic tools; they shaped our relationship with Catholic religion.

The friar’s dilemma

To understand the origins of these traditions, one must first inhabit the mind of their

inventors. Imagine you are a Franciscan friar in the 16th century. You have just stepped

off a ship into a world that defies every category of your existence.

You are standing in a land where the Bible has no authority, where the name Dios (God)

evoke no recognition, and where Jesus is a ghost of a foreign land. But the theological

silence is the least of your disorientation.

In the world you left behind, humanity was crafted in the image of God. Here, you find a

civilization convinced of the inverse: humans were not made to reflect the gods but

to sustain them. The relationship is not one of adoration, but of metabolic necessity.

Without human intervention, the cosmos collapses.

Here, nature is not a backdrop for human morality but a deity in itself — the stars do not merely shine; they dictate the rhythm of breath and blood. Even the architecture rejects you: in Castile, the church is a sanctuary for the flock; here, entering the House of any God is an unthinkable transgression, a terrifying privilege reserved only for the tlatoanis and warriors who feed the Gods.

The scale of this “New World” is also bewildering — larger than the Kingdom of Castile, a

patchwork of nations with distinct tongues and pantheons. But the deepest chasm is not

linguistic; it is conceptual.

How do you explain the unique and linear path to salvation — final judgment — to a

people who live in a universe of relentless, cyclical duality? Binary tensions structure their reality: life and death, male and female, rain and drought, light and darkness.

They do not seek “goodness” in the Christian sense; they seek balance. To them,

morality is not about avoiding sin; it is about maintaining cosmic equilibrium. Actions

have immediate, tangible consequences in the here and now, not in a distant afterlife.

The collision of these two worldviews must have been absolute. How do you translate

the concept of “sin to a mind that sees only “chaos”? How do you preach “grace” to a

culture obsessed with “order”?

Facing this metaphysical abyss, the friars stopped trying to translate the untranslatable.

Instead, they looked for the one language that transcends doctrine: the seasons.

Where calendars converge

Every religion, at some point in its history, follows the rhythm of the harvest. And so it

was not difficult for the friars to spot the parallels between European and Indigenous

calendars. Across cultures, key festivals clustered at the end of the agricultural year,

celebrating renewal, abundance and hope.

In Central Mexico, one of the most important of these celebrations was Panquetzaliztli,

or the “Raising of the Banners.” Despite what many modern retellings suggest,

Panquetzaliztli was not a single-day festivity, but the name of the 15th twenty-day

month — dense with mythic reenactments, sacrifices and ritual drama.

It commemorated the miraculous birth of Huitzilopochtli, the Sun God, born of the

immaculate conception of the goddess Coatlicue. His 400 siblings, consumed by

suspicion and rage, attempted to kill their mother for what they perceived as infidelity.

But Huitzilopochtli, emerging fully armed from her womb, defeated them all — a cosmic

allegory of light triumphing over darkness.

Panquetzaliztli functioned simultaneously as a method of preserving Mexica cosmic

tradition and as a terrifying reminder to subject nations that the Mexica were the chosen

children of the sun. The month-long observance was a crescendo of ritual acts,

escalating in intensity until the final three days.

The Incarnation (Day 18):

The climax began with an act of sacred sculpting. Priests and devotees fashioned a life-

sized effigy of Huitzilopochtli from a paste of toasted corn, amaranth and agave honey,

to be consumed on the last day.

The Enthronement (Day 19):

The figure was carried to the summit of the Templo Mayor. There, overlooking the valley,

it was displayed for public adoration before being processed inside the sanctuary. The

day was filled with incensing, dance and liturgy, marking the god’s presence among his people.

The Sacrifice and Communion (Day 20):

The final day brought a spectacle of movement and blood. A high priest, trailing a

massive banner in the shape of a serpent, led a procession that wound through the city

for nearly four hours. This was a harvest of souls: the procession visited various sites

and temples to collect war prisoners and march them back to the feet of Huitzilopochtli.

Inside the temple precinct, a ritualized skirmish was staged among the prisoners

destined for the stone. But the violence extended to the god itself. In a symbolic slaying, priests hurled darts into the heart of the amaranth Huitzilopochtli. The “dead” god was

then broken into pieces. The heart and limbs were distributed to the nobility, while

smaller bones made of the same seed-paste were given to the commoners.

The day concluded with social renewal marked by the birth of Huitzilopochtli, followed

by a solemn sermon reinforcing the necessity of these rites to maintain the universe.

Panquetzaliztli was a rigorous, blood-soaked affirmation of power.

Creating Navidad

So picture the friars now, standing before a ritual that resembled — uncomfortably

so — the structure of their own faith. Here was a god born of a virgin, and here was

bread made sacred and consumed in his name.

The horror must have been real. In the pageantry of Panquetzaliztli, they saw a

narrative bridge from indigenous faith to Catholic doctrine. Huitzilopochtli’s story could

be reframed through the miracle of another birth: that of the Son of God, who required

not blood, but prayer.

But they had a tonal problem. While the Valley of Mexico pulsated with the martial rhythms of Panquetzaliztli, the Old World was immersed in a deeply different frequency:

Advent.

In the 16th-century Catholic imagination, the weeks leading up to Christmas were a

period of rigorous spiritual hibernation. Beginning on the Sunday closest to November

30 and stretching to Christmas Eve, Advent was a season of “little Lent.” The churches

were draped in purple—the liturgical color of penance. The atmosphere was a complex

emotional alloy of repentance, fear and a desperate hope for redemption. The Advent

wreath, with its four candles nestled in evergreen, marked the slow, deliberate conquest

of light over darkness, week by week.

How could such a somber season compete with the vibrancy of the Indigenous rites?

The friars found their answer in a tradition already popular in Seville: the Misas de

Aguinaldo. They realized that if the Indigenous people were eager to celebrate during

the days of Panquetzaliztli, the Church had to offer them back their own “ritualistic

sacred days,” but repackaged.

And so, nine days before the Nativity, the solemnity was deliberately cracked open. At these special dawn masses, the church offered Eucharist and aguinaldos — gifts of dried

fruit, sweets and food.

The clergy officially maintained that the overflowing pews were a testament to spiritual

fervor. But historical chronicles from the era paint a more human picture: they describe the churches turning into raucous romerías — chaotic festivals where the faithful were

driven less by a hunger for God than by a very literal hunger for the treats.

It was this specific tension—between the solemn requirements of the liturgy and the

irrepressible human desire for celebration—that the friars harnessed. They exploited

this crack in the solemnity to erase the memory of the pre-Hispanic gods, replacing

sacred amaranth with aguinaldo.

The theater of conversion

Conversion required more than treats; it required a story. And the friars’ most effective tool

was theater. During the same Advent season, at sunset, they began to stage short plays

designed to educate the populace on the importance of the nativity.

As early as 1539, plays like “The Conquest of Jerusalem” were performed not for

entertainment but for edification. Since the Indigenous people were often terrified to enter the house of God, open chapels were built as hybrid sacred stages. There, beneath the

sky, faith became as much doctrine as it was spectacle.

By the 17th century, the stories evolved. The focus shifted from grand liturgy to human

a drama where the audience could see themselves reflected in the moral journeys of

shepherds, angels and devils. The tone became warmer, more familiar. Thus were born the pastorelas: plays that dramatized the humble pilgrimage of Indigenous shepherds

seeking the newborn Christ, repeatedly tempted by evil with the seven capital sins, but

never defeated.

The audience might not yet grasp the dogma, but they understood ritual repetition,

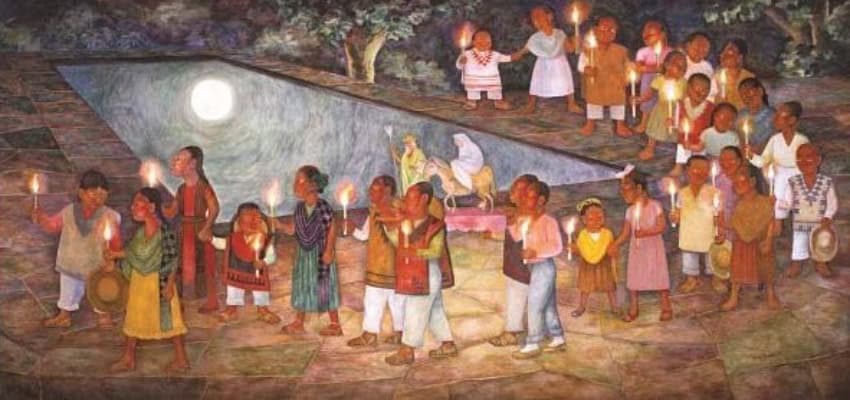

music and dance. So around pastorelas bloomed the posadas — popular processions

where communities reenacted Mary and Joseph’s search for shelter. People carried

candles and sang villancicos, local carols written in the vernacular. Between the verses

and the laughter, Catholic doctrine quietly took root.

It was, in essence, a masterclass in cultural negotiation disguised as a three-part

celebration: the Misas de Aguinaldo, the pastorelas and the posadas.

Secularization and sentiment

By the 19th century, Mexico had legally divorced church and state. Religion retreated

from public life, but its rituals remained, dressed in the garb of community. The posadas

escaped the church walls and spilled into streets and courtyards. What had begun as

catechism became shared festivity.

Some clergy saw the change as irreverent. But it was a fulfillment of the very

syncretism that had birthed the tradition centuries earlier: a joyful coexistence of the

sacred and the human.

From Navidad to Christmas

In today’s Mexico, the overt religiosity of the season has faded further still. Many attend

mass only out of habit or family duty, if at all. The air is no longer filled with the scent of

copal or the solemnity of Latin but with English-language carols translated into

Spanish — the soundtrack of a globalized December.

As a Catholic, I admit to feeling a pang of melancholy watching the deep theological

weight of Navidad morph into a secular exchange of goods (even as I open my own

gifts with Bing Crosby crooning in the background, of course). Yet, I also recognize the

profound irony of my nostalgia. Five centuries ago, an Indigenous woman must have felt

the same disorientation and loss as she watched the sacred banner of Panquetzaliztli give way to the manger of Christmas.

But perhaps to mourn this shift is to misunderstand the very nature of our culture. The

essence of Mexican identity is not purity, but adaptation. Faith becomes story, story

becomes ritual, and ritual becomes survival.

Whether we offer amaranth to the sun, prayers to the Christ Child, or simply time to our

families, the impulse remains unchanged. We are still doing what the Mexica and the

friars did before us: gathering together to light a fire against the longest, darkest nights

of the year, driven by the stubborn, ancient hope that the light will, inevitably, return.

Maria Meléndez is an influencer with half a degree in journalism