Amigos, so far I’ve told you about writers that I think are quintessential for

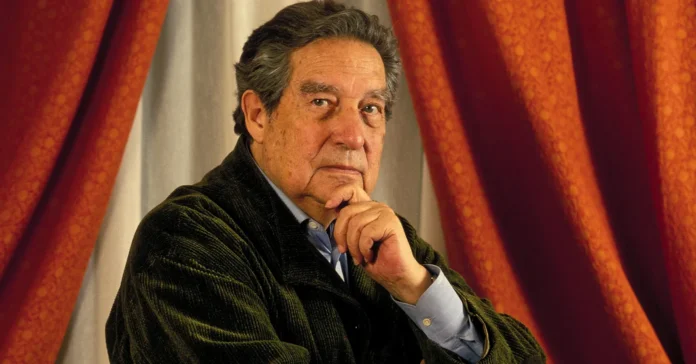

understanding from another perspective what Mexico really is. Of them all, Octavio Paz

is my favorite — admitting that in mixed company, and especially in front of women, this admission can be controversial.

Paz is the only Mexican writer to have won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Yet for many,

the prize is tarnished by his friendliness with the ruling party of his era, the PRI. For

some women, the Nobel means little in light of his treatment of his ex-wife, the writer

Elena Garro.

More than merely a writer, Paz was a thinker who knew how to use language. His work

spans poems, essays, cultural criticism and philosophy. He developed as both a writer

and a diplomat, a dual life that let him see Mexico from afar and return with a clearer

view. His prose and poetry capture the tensions of a nation shaped by conquest,

religion, revolution, solitude and a long, fraught effort to reconcile Indigenous and

European inheritances.

To read Paz today is to wrestle with the same conflicts he confronted throughout his life:

art and politics, national identity and global exchange, solitude and community.

The making of a poet and philosopher

Octavio Paz was born in Mexico City on March 31, 1914, into a family marked by both

intellectual engagement and the upheavals of the Mexican Revolution. His grandfather,

a liberal intellectual with a substantial library, introduced him early to literature. Paz

published his first poetry collection, “Luna Silvestre” (“Wild Moon”), at just 19.

He briefly studied law at the National University of Mexico before abandoning it for

writing and journalism. In 1937, he traveled to Spain during the Civil War and joined the

Second International Congress of Anti-Fascist Writers — an experience that left a lasting

mark and revealed a pattern: Paz habitually looked outward, toward other countries and

traditions, to better understand his own. Hearing firsthand the conversations and

laughter of those behind the opposing lines convinced him that people on the other side

were human too, which made him more inclined toward tolerance and a readiness to

understand their perspectives.

After World War II, he entered Mexico’s diplomatic corps, spending two decades

abroad. His postings took him to the United States, France, Japan and India — years

that profoundly shaped his thinking. In Paris, he engaged with surrealism and European

modernism; in Japan, he absorbed Zen aesthetics and the discipline of haiku; in India, he

encountered Hindu and Buddhist thought. These cross-cultural encounters broadened

his sense of what poetry and identity could be, sustaining an intellectual curiosity that

resisted simplistic ideological labels.

The view from outside: Writing Mexico’s identity

Paz’s most celebrated work remains “El Laberinto de la Soledad” (1950), translated

as “The Labyrinth of Solitude.” It is not a conventional history of Mexico. It is an inquiry

into the psychological and cultural forces that shape Mexican experience.

Paz argued that Mexicans navigate a profound sense of solitude forged by the legacy of

conquest and mestizaje (cultural and racial mixing), and that this solitude expresses

itself in ritual, celebration, death, music and language. His reflections on

masks — symbolic and emotional — suggest a people negotiating between pride and

defensiveness, intimacy and distance.

His interpretations of fiestas, Day of the Dead rituals, and the figure of La Malinche are

not folkloric descriptions but attempts to chart a collective emotional landscape. “The

Labyrinth of Solitude” became essential reading in Mexico and abroad for anyone

seeking to understand the paradoxes at the heart of Mexican identity: joy entangled with

melancholy, pride layered over trauma.

Poetry as inquiry

Paz’s poetry is as probing as his essays. His early work reveals influences from

Marxism, surrealism and existentialism; his later poetry immerses itself in eroticism,

time and the inner life of language.

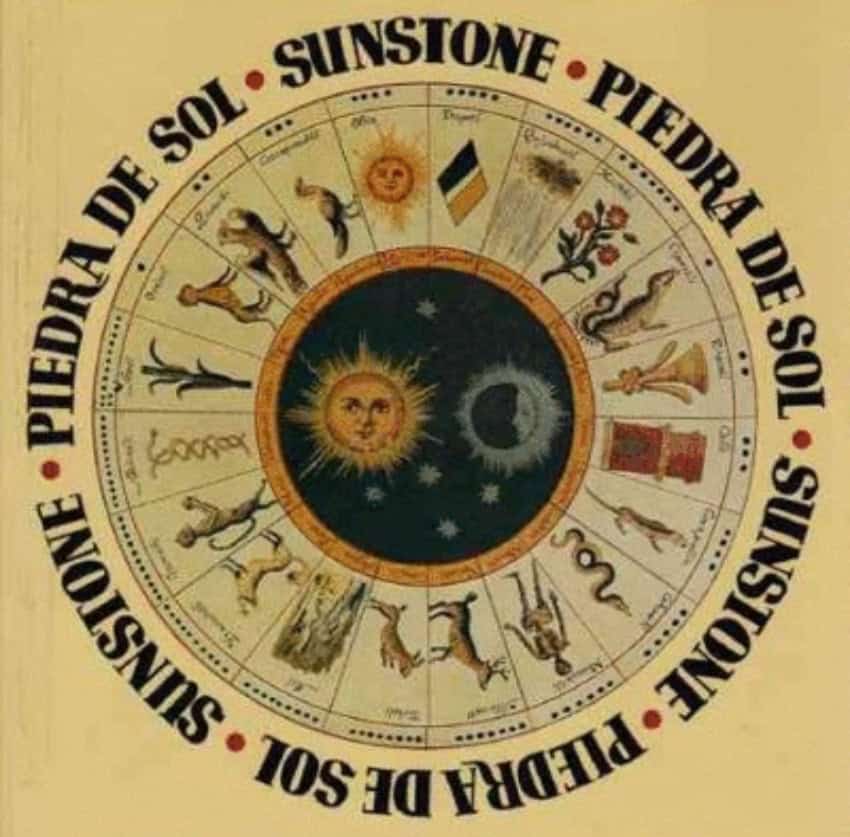

His long poem “Piedra de Sol” (“Sunstone”), published in 1957, is widely considered his

masterpiece. Structured around the 584-line cycle of the Aztec calendar, the poem

offers a circular meditation on love, time, memory and myth. It earned international

acclaim and was central to the body of work recognized by the Nobel committee.

Paz believed poetry did more than reflect reality — it transformed perception. His later

works often blur the boundaries between lyricism and philosophy, asking readers to

reconsider what it means to read, experience and interpret.

Politics: Between dialogue and dissent

Paz’s political positions resist easy categorization. Early in his career, he aligned himself

with left-leaning causes but never adhered strictly to ideological dogma. Experiences in

Spain, France and the United States made him cautious of rigid political identities long

before Cold War polarities hardened across Latin America.

His most famous political rupture came in 1968, when he resigned as Mexico’s

ambassador to India in protest of the government’s massacre of student demonstrators

in Tlatelolco. Few public intellectuals within the establishment took such a visible stand,

and his resignation cemented his reputation as someone willing to break ranks on

matters of principle.

Yet in later decades, he supported political and economic reforms that put him at odds

with more radical currents. He welcomed openings within Mexico’s political system,

defended liberal democratic ideals, and openly debated figures across the ideological

spectrum.

One of the most emblematic moments occurred during a televised conference in the

early 1990s, when Paz invited Mario Vargas Llosa to speak. After Paz remarked that

Mexico was the only Latin American country without a dictatorship, Vargas Llosa

famously countered that Mexico lived under “the perfect dictatorship.”

His discomfort stemmed partly from the fact that he was, indeed, close to certain

political actors. He believed that the new generation of PRI politicians in the late 1980s

and the 1990s were genuinely attempting to steer Mexico toward greater political openness. History ultimately showed that the party was undergoing a deep internal rupture and that there were figures committed to democratic reform.

For critics, this proximity to power damaged Paz’s credibility. For admirers, it

underscored his belief in dialogue rather than dogma. Whether one agrees with him or

not, his political thought was never simplistic; it reflected a consistent skepticism toward

authoritarianism and a faith in humanistic reason.

A cultural bridge and critical legacy

Paz’s influence extended well beyond his books. Through the literary

magazines Plural and later Vuelta, he helped shape intellectual debate across the

Spanish-speaking world. Vuelta, in particular, became a crucial forum for essays on art,

politics and culture, drawing contributions from Latin America, Europe and the United

States.

Paz anticipated discussions that today dominate cultural studies: the intersections of

identity and history, the weight of colonial legacies, and the friction between tradition

and modernity. His sustained engagement with Asian philosophies long before “global

literature” became a buzzword marks him as a thinker ahead of his time.

Why Octavio Paz still matters

Nearly three decades after he died in Mexico City in 1998, Octavio Paz remains

central to discussions of Mexican culture and identity. His writings are not relics but

living documents that invite readers to ask difficult and often uncomfortable questions.

Paz endures not because he offered final answers but because he insisted on

formulating the right questions:

What does it mean to be Mexican after conquest and revolution? How can poetry reveal

our deepest anxieties and desires? How do culture and history shape the self? Can

dialogue across traditions deepen our shared humanity?

These are not abstract inquiries. They continue to resonate across Mexico — on its

streets, in its newspapers, and in the diverse voices shaping its future.

Where to Start?

If you want to explore Paz’s work with greater depth, here are some accessible books in

English:

“The Labyrinth of Solitude” — the essential book for understanding Paz’s view of

Mexican identity.

“In Light of India” — reflections on India, selfhood and cross-cultural encounter.

“Sunstone” — his most celebrated long poem, and a modern classic.

“The Bow and the Lyre” — Paz’s philosophical meditation on poetry, language and

meaning.

Octavio Paz may remain uncomfortable for some readers — too nuanced, too elusive,

too willing to confront contradictions. But it is precisely that refusal to be easily

categorized that makes him one of Mexico’s most enduring cultural voices.

Lastly, if you’re wondering what happened with his ex-wife, and why many feminists

despise Paz, stay tuned for the Elena Garro piece.

Maria Meléndez writes for Mexico News Daily in Mexico City.