The National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has announced the recovery of three codices created by Indigenous scribes between 400 and 450 years ago and containing valuable details about the history of Mexico.

With colorful pictographs and other information, the codices shed light on the story of Tenochtitlán, the capital of the Mexica empire upon which modern Mexico City was built.

Because they had remained in the possession of a family for generations, these codices had gone virtually unseen by anyone for ages.

“It is as if a Rembrandt or a Velázquez appeared today,” said María Castañeda de la Paz, a researcher at the Anthropological Research Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “It’s extraordinary.”

Baltasar Brito Guadarrama, director of the National Library of Anthropology and History (BNAH), expressed similar excitement at INAH’s Wednesday press conference.

He said it was “a wonder that, after several centuries, new, very interesting and very beautiful materials continue to appear that enrich the national cultural heritage.”

The documents are known as the Codices of San Andrés Tetepilco and can be considered a continuation of the Boturini Codex, which depicts the migration of the Nahua peoples, including those who would become the Mexica (Aztecs) from Aztlán, said to be where the Mexica originated.

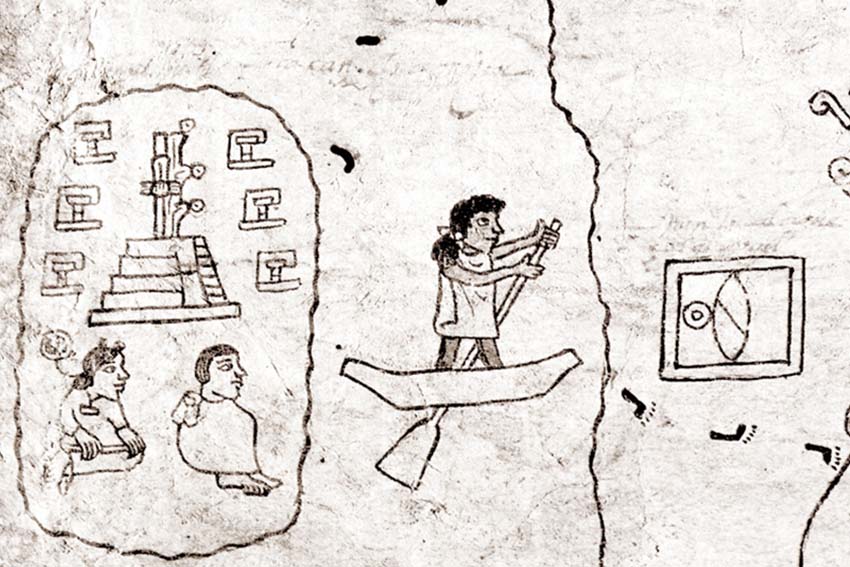

The codices were created in the late 1500s and early 1600s by tlacuilos (chronicler scribes) in the town of San Andrés Tetepilco, located in what is now the borough of Iztapalapa in southeastern Mexico City.

“It is as if a Rembrandt or a Velázquez appeared today,” said María Castañeda de la Paz, a researcher at the Anthropological Research Institute of the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “It’s extraordinary.”

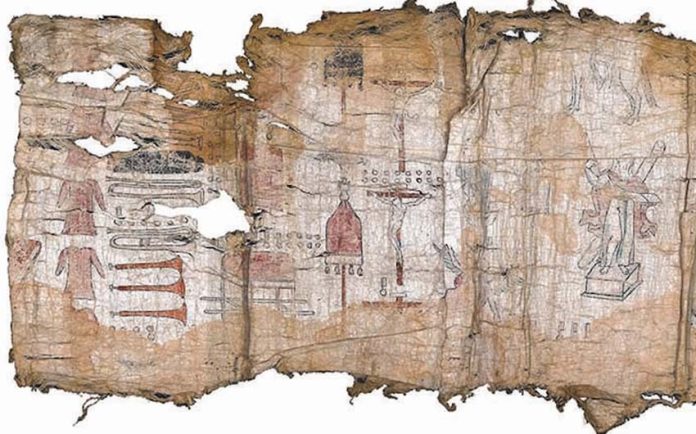

The largest one, the Tira de Tetepilco, tells the history of Tenochtitlán from its founding in the 1300s, providing details about its rulers in pre-Columbian times, the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1519 and the colonial period through the arrival of viceroy Juan de Mendoza y Luna in 1603.

Another codex is an inventory of the church of San Andrés Tetilco. It is made of two sheets of amate paper glued together, on which a white layer of lime was applied.

A final codex contains historical and geographic information related to San Andrés Tetepilco itself.

The codices contain paintings from Indigenous traditions as well as texts in Nahuatl and Spanish, written in the Latin alphabet, making it part of the tradition of “mixed” codices.

María Castañeda recalled being invited to a private home in Mexico City some 15 years ago for a first look at the artifacts, which left her breathless.

The family, which wishes to remain anonymous, eventually turned them over to the government, but only after various entities committed to the conservation and preservation of Mexican cultural heritage helped raise 9.5 million pesos (US $566,500) as payment, according to an INAH press release.

INAH described the acquisition as a milestone comparable to the authentication of the Mayan Codex of Mexico six years ago.

These three “new” documents are among some 200 Mesoamerican codices out of approximately 550 that are recognized in the world. Henceforth, the artifacts will remain in the public domain, protected in a vault in the National Library of Anthropology and History in Mexico City.

With reports from Aristegui Noticias, El País and La Jornada