From the towering Angel of Independence, where the remains of Mexico’s founding heroes rest, to the anti-monuments erected by social movements, the statues and markers along Mexico City’s Paseo de la Reforma both commemorate the nation’s long history and show how different parts of society dispute the meaning of that history or fight to make their voices heard in its telling.

When we watch Women’s Day marchers paint the metal barriers around the Caballito statue or relatives of victims of forced disappearance turn the Glorieta del Ahuehuete roundabout into the Glorieta de las y los Desaparecidos, we’re seeing disputes over the nation’s collective story. In that sense, President Claudia Sheinbaum’s unveiling of six new statues of historical figures on Reforma, all Indigenous women, is a highly symbolic intervention by the state — especially since one of the figures commemorated has for generations been a synonym for treason to the country.

View this post on Instagram

The president said as much at the unveiling ceremony on Wednesday morning, calling the new monuments “a firm symbol against racism, classism and misogyny.” The new statues form part of the existing Paseo de las Heroinas (Promenade of the Heroines), a sculpture walk established during Sheinbaum’s tenure as Mexico City’s head of government, which introduced statues of female heroes of the country’s history onto Reforma for the first time. So who are the six Indigenous women joining the Paseo de las Heroinas?

Malintzin: The interpreter, revisited

The strange group of foreigners to whom she was given as a slave in 1519 called her Marina, to which the Mexica (Aztecs) added the honorific “-tzin,” making her Malintzin, which the Castillians turned back into Spanish as Malinche. In Mexico, that name means everything from a preference for European trends to outright treason.

In another time, Malintzin’s inclusion in the Paseo de las Heroinas might have been highly controversial. But artists and scholars of Mexican colonial history have done much in recent years to rehabilitate her image from that of a traitor to that of a gifted polyglot and enslaved woman who did what she could to survive in a world turned upside down. President Sheinbaum’s own government staged Mujeres del Maíz at the end of 2025 to “revalorize, recognize and vindicate Malintzin in a different way,” in the president’s words.

Tz’akbu Ajaw: The Red Queen of Palenque

In 1994, 24-year-old archaeologist Fanny López was helping to stabilize Temple XIII of Palenque, one of the most important city-states of the Classic Maya period, located in modern-day Chiapas. Palenque had been famous for decades as the site where the fabulous tomb of Pakal the Great, lord of Palenque and the fifth-longest-reigning monarch in world history, had been found in 1952.

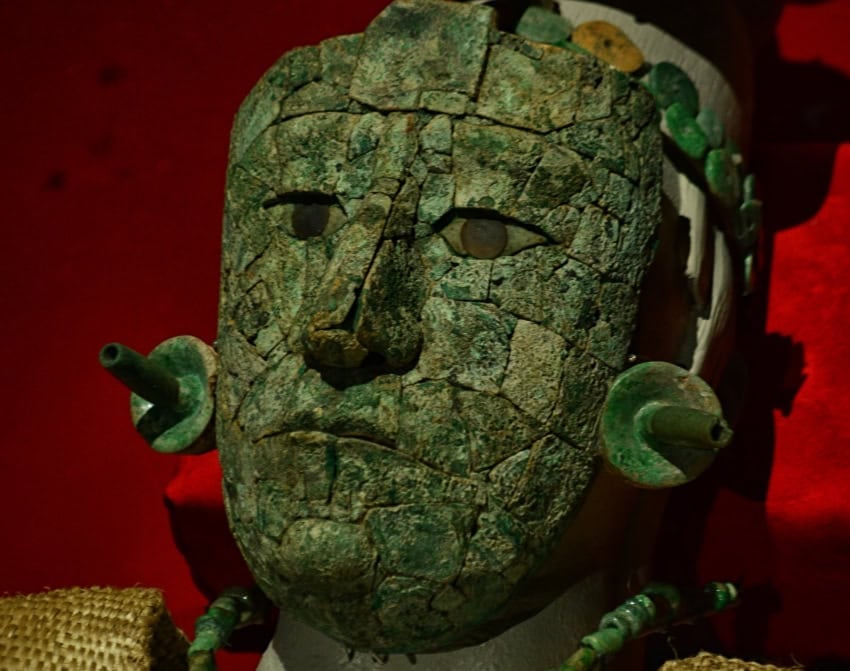

López discovered that Temple XIII held a tomb too, and as the Chiapas native and her team slid back the lid of its sarcophagus, their eyes met something incredible: the remains of a woman wearing an enormous malachite mask, surrounded by treasures and covered entirely in crimson cinnabar dust. Clearly, this woman had been important and had some relationship to Pakal, but there were no glyphs to tell for certain who she was. Was she the king’s mother? His grandmother? The answer has not yet been definitively proven, but most specialists now believe that the noblewoman, who has come to be called the Red Queen for how she was buried, was Ix Tz’akbu Ajaw, Pakal the Great’s wife.

Much is still unknown about the Red Queen’s life. Born around A.D. 610 into the royal family of Uhx Te’ K’uh, a Maya city in present-day Tabasco state, Lady Tz’akbu Ajaw married Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal as a teenager. Their two sons would both succeed their father and rule Palenque, showing the truth of Tz’akbu’s name, which means “Queen of Countless Generations.”

Pakal earned the sobriquet of “the Great” by leading Palenque out of a period of political turmoil and into its period of greatest wealth and splendor through an ambitious program of public works. Tz’akbu Ajaw’s name and titles feature prominently on the monuments of her husband’s time, suggesting an important role in Palenque’s public life.

Tecuichpo: Last empress of the Mexica

When she died in 1551, Isabel Moctezuma was the richest woman in the colony of New Spain, holding extensive tracts of land and Indigenous slaves. This is not only remarkable because she was an Indigenous woman, but because she certainly died poorer than she was born: Isabel, also called Tecuichpo, was born Tecuichpoch-Ixcaxochitzin. Her parents were Moctezuma II, the Mexica king who ruled over most of Mexico and was overthrown by the Spanish, and Teotlalco, a princess of the city of Ecatepec.

Despite being a woman living in a world rocked by colonial invasion, Tecuichpo exercised what agency she had as an important noblewoman. First wed as a child to her father’s general, Atlixcatzin, Tecuichpo married Cuitlahuac and then Cuahtemoc, Moctezuma’s successors as leaders of the Triple Alliance, before being wed to a series of Spanish conquistadors.

In the Americas, Spanish colonialism was most effective wherever it came up against a settled, stratified society whose ruling class it could decapitate and replace, which meant that cooperative Indigenous nobles were key in setting up the new colonial order. After accepting Christian baptism and a new name, Doña Isabel was recognized as her father’s legitimate heir, a status she used to recover some of Moctezuma’s possessions through the Spanish courts. As royally certified nobility, Isabel’s descendants among Europe’s aristocracy, including the current dukes of Alba and Segorbe in Spain, continue her father’s line today.

Ñuñuu Dzico Yecu: Shield of Jaltepec

The Ñuu Savi, better known as the Mixtecs, are one of Mexico’s largest Indigenous groups today. The Mixtec peoples never unified as a single empire; they were traditionally divided into competing kingdoms called ñuu. That competition was to mark the life of Lady Six Monkey, named for the day of her birth and born into the ruling family of the city of Jaltepec in the late 11th century. Her early years took place in the context of bloody struggle with Jaltepec’s rival kingdom of Tilantongo, and as a teenager, she became engaged to the ruler of the city of Huachino. When noble vassals of Huachino opposed the match and publicly insulted her, Six Monkey went on the offensive, leading troops against the rebels, capturing their cities and taking them back to Huachino for ritual execution. Her campaign — a striking example of the gender equality that could be found among Mixtec elites — was a total success, and Six Monkey took the name War Quechquemitl, for the garment she wore from then on, decorated with symbols of war.

The second part of Lady Six Monkey-War Quechquemitl’s life was shaped by her conflict with the man who would become one of the most powerful rulers in Mixtec history: Lord Eight Deer Jaguar Claw, king of Tututepec. A member of the ruling family of Tilantongo, Eight Deer had forged a huge sphere of influence in Oaxaca by the turn of the 12th century and had long nursed a grudge against Jaltepec and Huachino.

Seeking to stop Eight Deer’s rise, Six Monkey had his brother assassinated in 1100 and moved to crush her rival in open warfare. She lost, and Huachino was destroyed, while Six Monkey and her husband were captured and executed by Eight Deer. But the queen got some measure of revenge in the end: Six Monkey’s son Four Wind was taken by Eight Deer as a hostage, raised in his court and eventually installed as the puppet ruler of Jaltepec. Four Wind never forgot what Eight Deer had done to his mother: As a grown man, he led a rebellion against Eight Deer, executing the great lord and marrying his daughter so that the three cities were finally united as Six Monkey had dreamed of.

Xiuhtzaltzin: First queen of the Toltecs

The fall of the great city of Teotihuacán marked the beginning of Mesoamerica’s Postclassic period, and one of the cities that came to fill the space left behind was Tollan, in what is now Tula, Hidalgo. Tollan’s inhabitants, the Toltecs, left no written records, so much of the information we have on them comes through the oral histories of the Mexica — whose civilization rose centuries after Tollan’s fall and who may have called all great builder cultures Toltecs — as viewed through the lens of Spanish chroniclers. That means that taking narratives about the Toltecs at face value can be tricky, but the exceptional circumstances of the reign of Xiuhtzaltzin might point to her actually having existed.

Only men could succeed to the throne of Tollan, and Xiuhtzaltzin’s husband was Mitl, the 11th king of the city. When Mitl died, the throne should have passed to their son. But Xiuhtzaltzin was so beloved by the Toltecs, tradition says, that her son declared that he would rather be his mother’s vassal than her successor, and so Xiuhtzaltzin became the only woman ever to rule Tollan. If Xiuhtzaltzin’s face looks familiar to you, that’s not by coincidence: 2025 was declared the Year of the Indigenous Woman by the federal government, and the steely-eyed woman in a huipil and earrings who appeared on the government’s official letterhead for all of last year is a representation of Xiuhtzaltzin herself.

Eréndira: Warrior princess of the Purépechas

When the Spanish arrived in Mexico in 1519, the Mexica were the great power in the country’s Central Highlands; second after them were the neighboring Purépecha, who ruled much of Western Mexico. The Purépecha polity had its seat in Tzintzuntzán, Michoacán, and its last king was Tangaxuan II. Not believing that he could resist the Spanish, Tangaxuan accepted baptism and chose to become a vassal of the invaders when they reached his domains in 1522. Though they looted his city anyway, the Spanish allowed him to continue ruling until 1530, when the infamous conquistador Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán tortured and burned him at the stake.

Legend tells that Tangaxuan’s daughter Eréndira, infuriated by her father’s weakness in the face of the Spanish, took it upon herself to lead the Purépecha resistance. Part of her story revolves around Eréndira becoming the first Indigenous person to learn to ride a horse, and the figure of the princess on a white horse leading Indigenous combatants against the Spanish invaders is a powerful symbol of the Purépechas and the state of Michoacán, depicted in artwork like Juan O’Gorman’s famous mural at the Gertrudis Bocanegra library in Pátzcuaro.

Was Eréndira real? It’s hard to say. Colonial-era records don’t mention her, although the “Relación de Michoacán,” set down around 1540 by Franciscan friars in the region, does mention women as part of the anti-Spanish resistance. She first appears in collections of Michoacán’s oral stories collected in the early 20th century, but what’s clear is that her story, a tale of the thirst for dignity triumphing over acquiescence, is a much older one.

Diego Levin is a historical researcher.