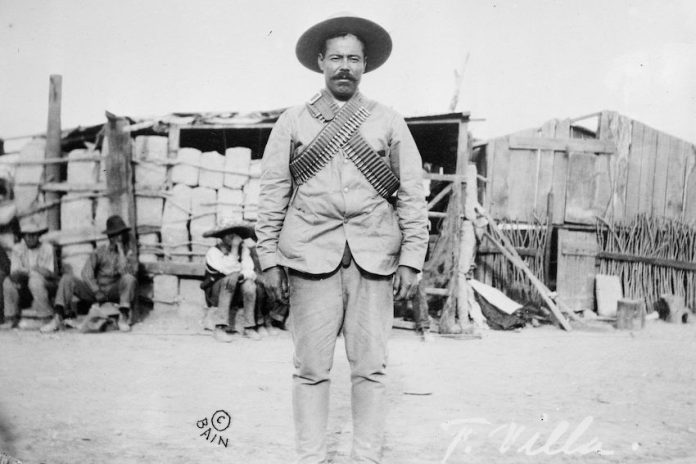

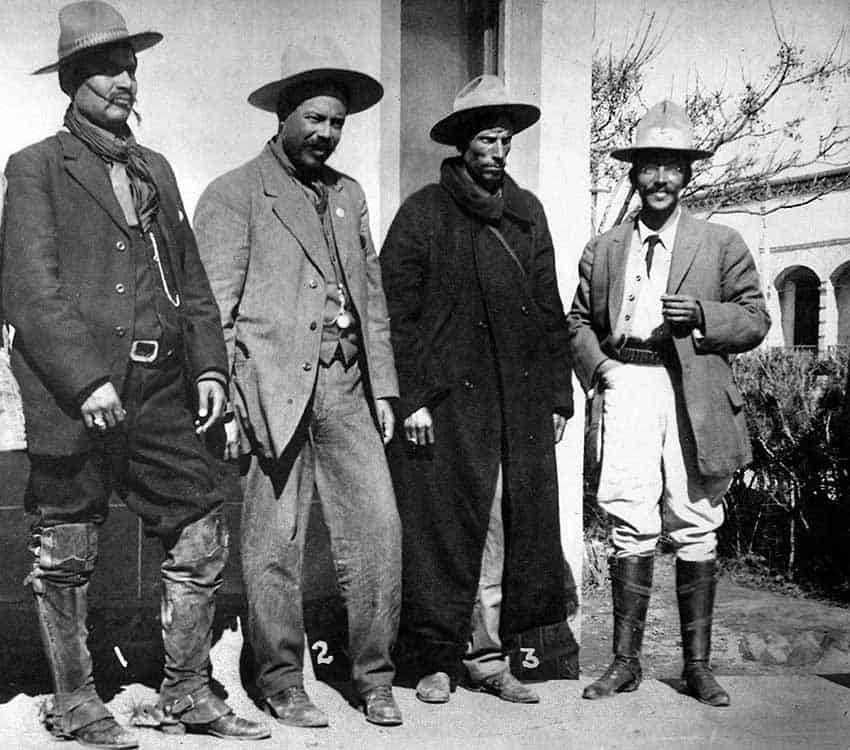

Francisco “Pancho” Villa, — born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula and known as the Northern Centaur — was the leader of the División del Norte (Northern Division) during the Mexican Revolution. Villa is said to have been a ruthless soldier and a thief.

The history of the 19th and early 20th centuries in Mexico is packed with revolutions and counter-revolutions. One of the most popular stories from this period is the legend of Pancho Villa and his missing treasure, thought to be buried somewhere in the Sierra Madre mountains.

It was common at the time for revolutionary leaders to protect their plunder by burying it in different locations. Even wealthy landowners buried their money underground to safeguard it from bandits.

Ever since the Mexican Revolution, people have searched for Villa’s buried treasure, which was plundered from local towns and villages throughout northern Mexico.

During the 30-year presidency of Porfirio Díaz, money was concentrated in the hands of wealthy landowners. After Francisco I. Madero’s appeal to begin a revolution in 1910, Villa decided to join the fight.

Money for armies was difficult to acquire, and as a result, many revolutionaries depended on looting to fund their operations. Villa may have been the most brazen and successful in funding his efforts this way.

There are two documented accounts of significant amounts of money being stolen by Villa and his men.

In 1999, the University of California, Berkeley, released a letter that was among the papers of Silvestre Terrazas — Villa’s secretary of finance and former governor of Chihuahua. The letter — written by Wells Fargo Bank in El Paso, Texas — details the looting of one of their trains by Villa and 200 of his men. They absconded with 122 ingots of silver — estimated to be worth at least US $3.4 million today.

Three weeks after the heist, Villa made a secret deal with Wells Fargo to return the silver for the sum of US $50,000 (the equivalent of US $1 million today). Villa returned only 96 bars of silver, leaving 26 bars unaccounted for.

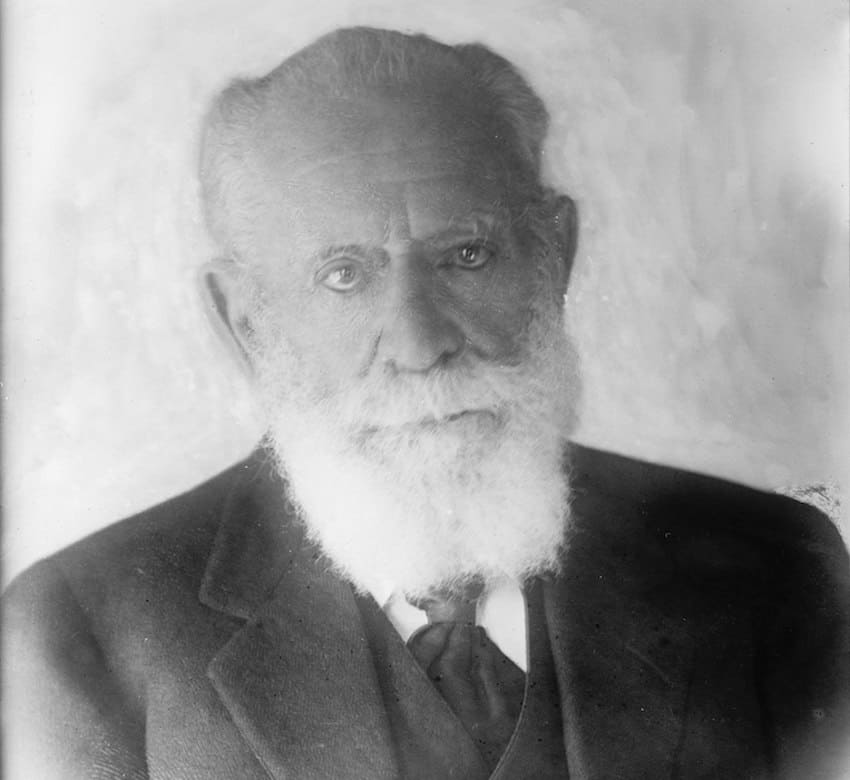

Another account says that in December of 1913, Villa and his men captured Chihuahua and robbed the Bank of Mexico located in the city. The director of the bank, Luis Terrazas, hid the bank’s gold in one of the columns of the building for protection and then fled to the British consulate for safety.

Villa captured Terrazas and took him from the consulate. His men then tore apart the bank until they located the gold – worth US $6.3 million – which was hidden in a column. The gold was never recovered.

Historians continue to scour the papers of Villa’s accomplices to try and discover more clues to the hidden treasure’s location. Several are housed at the University of California. The University of Texas holds the papers that once belonged to Lázaro de la Garza, who controlled the acquisition of arms and munitions from the United States for Villa and his army.

The United States National Archives also contains the FBI files on the smuggling, money transfers, and financial activities of Felix Sommerfeld — a German spy in Mexico — who also acquired arms for Villa.

Rumors abound over where Villa might have buried his hoard. Some think it was hidden in remote places in Durango, Chihuahua or Coahuila. Historian Carlos Castañón cites Torreón, Coahuila, as a possibility — it was a center of commerce and transportation during the Porfiriato, making it attractive to mercenaries.

The La Laguna area was taken over at least four times and looted for large sums of cash, gold, and silver. It is said that people in the region have dug hundreds of holes searching for the treasure. Searches of entire towns in northern Mexico have turned up nothing.

Another account says the gold was hidden in Tepuxta, north of Mazatlán, in a cavern used by Villa as a hideaway for him and his men.

The last documented sighting of Villa’s plunder – or at least part of it – was in 1915. In November that year, the El Paso Times newspaper detailed the raid of The Villa Stash House — as the FBI termed it — in El Paso, Texas.

The house used by Villa, his brother Hipólito and their wives was raided by Treasury Department agents based on the belief that it contained items smuggled into the United States.

The agents said they were tipped off by the purchase of a large safe by Mrs. Hipólito Villa. Inside the safe they found US $30,000 (almost US $1 million today) in diamond jewelry and more than $500,000 in US currency and gold coins (more than US $15 million today) – along with a solid gold medal inscribed: “To General Francisco Villa from the Constitutional Government for personal valor.”

The agents confiscated the jewelry and a French touring car parked outside but later returned them by court order, as there was no way to establish where they were purchased.

Since Villa’s death in 1923, treasure hunters have searched the Sierra Madre seeking the loot. Emil Holmdahl — the soldier-of-fortune who is suspected of stealing Villa’s skull from his grave and selling it to the “Skulls and Bones” secret society at Yale — spent decades searching for the hidden treasure but never found it.

The Villa Stash House has also been searched thoroughly. The abandoned house was purchased by entrepreneur Enrique Guajardo who began renovating it to turn it into a tourist attraction. During the renovation, he discovered a place hidden beneath the floorboards that he believes was used to hide Villa’s stash. But yet again, there was no sign of the treasure.

In 2020, the public gained access to the Villa Stash House, with a grand opening attended by curious historians from both sides of the border and a number of treasure seekers. Last year, a Las Cruces company, Construction Survey Technologies, was brought in to search the area where the house is located, using ground-penetrating radar (GPR) and other cutting-edge technology used for subsurface mapping and excavation.

But after over 100 years of searching in many different locations, Villa’s treasure remains elusive.

Sheryl Losser is a former public relations executive and professional researcher. She spent 45 years in national politics in the United States. She moved to Mazatlán in 2021 and works part-time doing freelance research and writing.