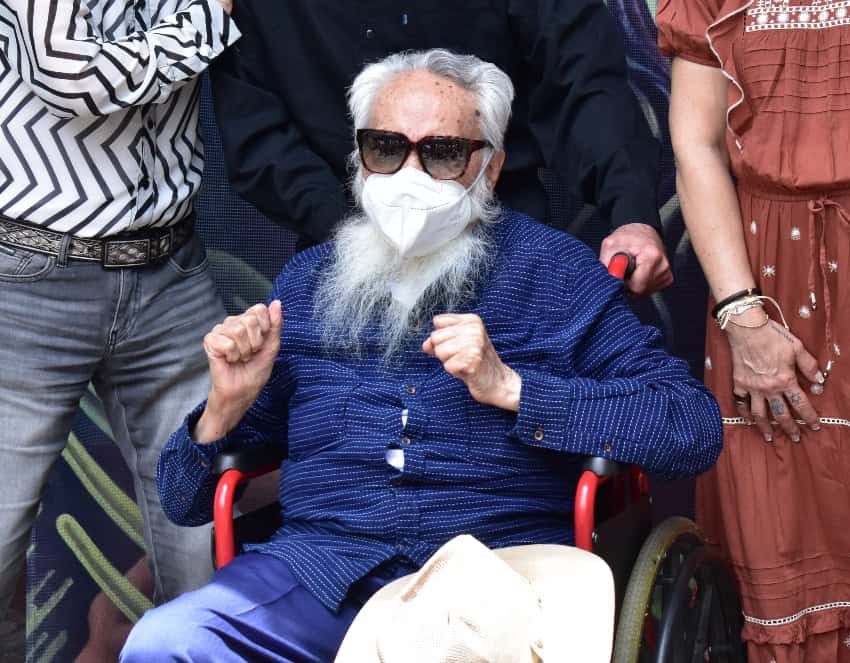

Guillermo Monroy was born into a completely different world, 102 years ago on January 7th, 1924. His eyes have witnessed a century of tragedies, yet he loves everything the light touches. After nearly 90 years of painting, he continues on his quest to find beauty in everything and everyone, even in the things he’s not fond of.

“I always have new ideas, but when I am working, I do what the painting asks of me, like a water spring that flows slowly. It will go away, but it will never end. I do feel tired, but when I’m there … it’s so beautiful I feel like I’m in elementary school again.”

A few days before his 102nd birthday, Monroy received us at his apartment in Cuernavaca, Morelos, where he has spent the last six decades of his life. The place is full of color, light and art materials of all kinds, including brushes, pastels and a big, empty canvas on his easel for an artwork he promised to his son, the renowned musician Guillermo Diego.

The kid

It is not easy to imagine him as a child. He spent his early years in Tlalpujahua, Michoacán, where he was born in 1924. After the mines ran dry, Monroy’s family left their hometown in the late 1920s and arrived in Mexico City to look for other ways to make a living. His parents, Sabás Monroy and Ignacia Becerril, had 10 children, no money and nowhere to go in the metropolis.

But the Monroys have always believed that things would work out. Guillermo’s dad left his family for a few hours at the Buenavista train station. He came back with a job and a place to live in Peralvillo. Some years later, they moved to Colonia Guerrero, one of the neighborhoods located a few blocks from Alameda Central, where La Esmeralda was situated. In this art school, he met Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who later became his beloved teachers.

The student

Monroy recalls arriving at La Esmeralda with wide eyes, amazed by everything that could be created there. “When I arrived at (the La Esmeralda School), I felt at home, (I knew) I had to stay there.”

Even though his family couldn’t afford for him to stop working — he was 16 by then — his father asked him to follow his passion because nothing compares to doing the one thing you love. “Don’t worry. We will always have some beans for you here. Do as you like,” his father told him.

Of course, it was all worth it. Monroy studied with some of the most important artists at the time (Francisco Zúñiga, Rómulo Rozo, Feliciano Peña, Raúl Anguiano, Agustín Lazo) and quickly became one of the four Fridos, the students of Frida Kahlo. Kahlo, who suffered from numerous health problems, had a brief career as a teacher at La Esmeralda. As a result of her worsening health, she invited her students to come over and paint in her garden, a suggestion from her pupils.

Of the students invited, only four attended the sessions devotedly: Fanny Rabel, Arturo García Bustos, Arturo Estrada and Guillermo Monroy. As time went by, they became more than students to Kahlo and Rivera; the young artists were now their colleagues and part of their family.

Frida, as a teacher, introduced them to mural art, a passion that has followed them their whole lives. They collaborated with Diego on the stone-mosaic murals at Anahuacalli, and some of them later created their own in Centro SCOP, representing the four elements. Monroy was in charge of the earth.

From pupil to master

He learned not just to be an artist but to be a teacher. He started working at Secundaria 1 in Mexico City. After that, he was invited to work at the Regional Institute of Fine Arts in Chiapas. Monroy continued his journey in local art schools, for he was interested in decentralizing culture. This path led him later to Acapulco, Guerrero, where his first and only son was born: Guillermo Diego, named after him and his master. The beach town would be the last stop before his final landing in the state of Morelos.

Coming from the regional schools in the south of the country, Monroy wanted to create a place where people from Cuernavaca and its surroundings could build careers in the arts; he was the missing piece of the foundation of the Instituto Regional de Bellas Artes de Cuernavaca (IRBAC). There, he spent his working years as a teacher and colleague of those pursuing careers in visual creation. He remembers his students and feels accomplished for helping them pursue their shared passion.

The fighter

Guillermo Monroy has devoted his life to fighting for what he stands for. He has lost friends and family along the way and has been lucky enough to make it out alive to continue with the commitment. He often thinks about Luis Morales, one of his dearest friends, who was killed during a protest for workers’ and tenants’ rights. Also, when he was in his early 20s, he joined the Mexican Communist Party through the invitation of José Chávez Morado. Since then, an essential part of his life has been dedicated to seeking justice and raising his voice.

The man, today

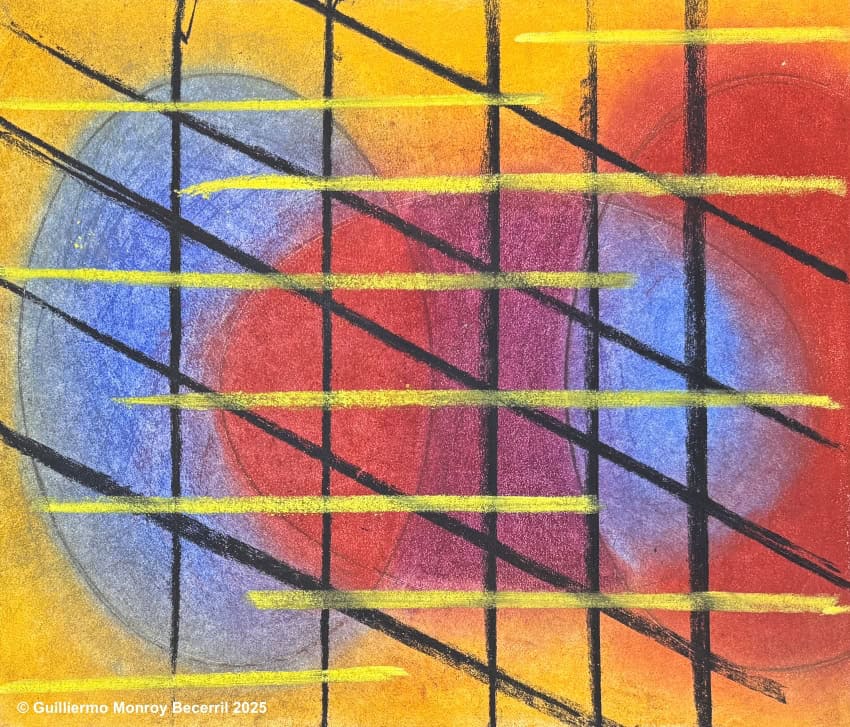

To this day, Monroy continues to learn anything he comes across. “I’m using pastels, I’m learning the technique,” he says while he displays his latest artwork in front of us. “It’s so simple and so wonderful. To know that something you couldn’t do before, something you were never taught, you are learning by yourself. You have to be the one to discover all this.”

At the moment, he is working on a series called “Dinamismo de una geometría plástica continua” (The dynamism of a continuous plastic geometry), an exploration of what are all the possible outcomes of a single line.

The couple of hours we spend with him are not enough to unveil a hundred years of existence. As the conversation draws to a close, he confesses that he enjoys telling his story. We can absolutely say we enjoy listening.

“I would love to tell you everything from start to end … As you listen to it, I feel it … What lies ahead? Who knows?”

We say goodbye to Monroy, not without asking what his expectations are for turning 102. His response — I think — is not very different from what he has always expected from life.

“What more do I want? I want for us to keep seeing each other, for us to be happy, to hug each other, to congratulate each other, and keep on moving.”

Lydia Leija is a linguist, journalist and visual storyteller. She has directed three feature films, and her audiovisual work has been featured in national and international media. She’s been part of National Geographic, Muy Interesante and Cosmopolitan.