On a walking trail near her home, middle schooler Jade encounters a creature that seems out of place in Atlanta – a jaguar. But this is no ordinary big cat. It’s actually a 500-year-old Indigenous Mexican man named Itztli who has the power to manifest as a jaguar. A friendship develops between the two: as Itztli shares stories in paintings of life under the Mexica Empire, Jade connects more deeply with her own Mexican heritage on a journey toward greater self-discovery.

This is the premise of “What the Jaguar Told Her,” a young adult novel by Mexican-American author Alexandra V. Méndez. Set in 2001, the multilayered plot covers subjects from the Spanish conquest of Mexico to the 9/11 terror attacks. Influenced by Mexican primary sources such as the Florentine Codex, the book was originally published in English, but a Spanish translation by Ariadna Molinari will be released on Oct. 10.

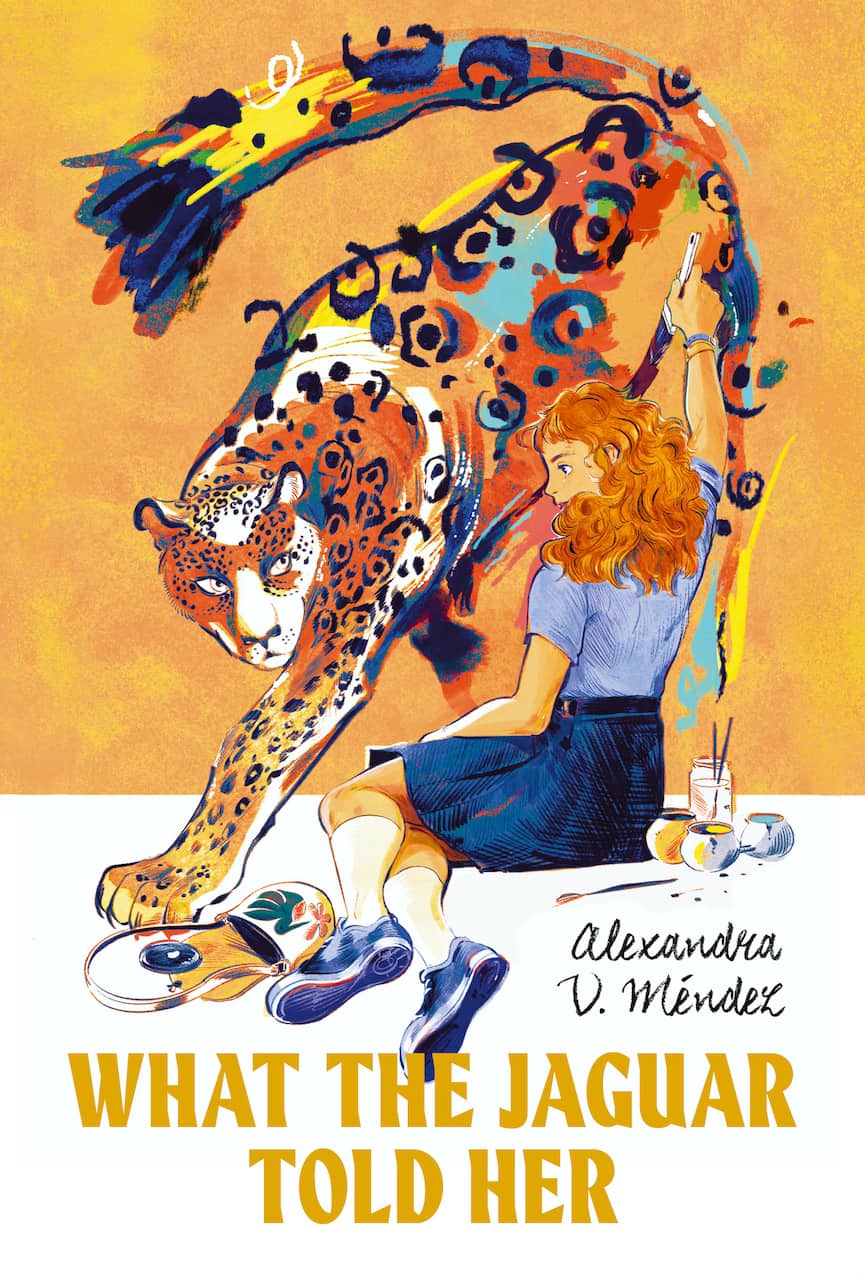

“It’s almost exactly to the day, one year, that the English [version] originally came out,” Méndez told me. “I’m very excited about this.” She’s likewise excited about Molly Mendoza’s cover art, which shows Jade’s emerging artistic talent bringing a jaguar to life.

“What the Jaguar Told Her” is informed by its author’s own family background: like Jade, Méndez has one Mexican and one white American parent.. While an undergraduate at Harvard College, Méndez interned at Dumbarton Oaks in Washington, DC, getting to see the museum’s pre-Columbian section. Later, as a doctoral student at Columbia University, she worked with Mesoamerican archaeology dating back to the 16th century.

“I wanted to make sure every story Itztli told had some basis in a primary source document,” Méndez said. “It doesn’t mean straight recreation, but primary sources are still important.”

In the novel, Jade’s connection to Mexico is further highlighted by such aspects as food and language, including both Spanish and Indigenous languages of Mexico.

“I definitely feel like I couldn’t tell the story without using words in Mexican languages,” Méndez said, mentioning scenes with Jade’s family as well as with Itztli. She notes that there is no English equivalent for Itztli’s role as a tlacuilo – the Nahuatl term for “a person who writes, and also paints, one and the same.” “It’s such a very specific thing,” Méndez said.

Itztli’s stories resonate for Jade, who fears she is losing touch with the Mexican side of her family. Her horticulturalist father is an Irish-American from Nebraska, while her CNN reporter mother has family roots in Mexico and in Chicago’s Mexican-American community. In addition to feeling uprooted by her family’s move from Chicago to Atlanta, Jade is grieving the loss of her beloved Abuelo and the void he leaves in terms of family knowledge. It’s that grief that makes her miss her Abuela, who’s still in Chicago, and to listen to Itztli’s stories.

“Part of what Jade wrestles with is that her Abuelo told her all these stories, but she can’t remember them,” Méndez said. “She needs to get in touch with her family and Abuela.” She added, “Itzli has a certain wisdom on that. He can get to Jade because he has 500 years of knowledge about what happened in those early days of encounters between Spaniards and Indigenous Mexicans.”

The narrative aims to present that encounter in a way that Méndez describes as more nuanced than previous portrayals. Itztli, for example, comes from a background that includes both the Mexica and the Purépecha, one of the peoples they fought against.

“There were many Indigenous groups with lots of reasons for wanting to overthrow the Aztecs,” Méndez said. “They were very resentful of them. It’s part of the reason, in fact, why Cortés and the Spaniards were successful in overthrowing the Aztec Empire or Mexica Empire … I think it’s important to kind of complicate some of the simplistic narratives we have.”

As the author incorporated history into the novel, she also worked with the theme of magical realism, notably with the scenes involving Itztli.

“Part of the challenge is having something that seems fantastical, like a jaguar turning into an old man who’s also a storyteller and an amazing painter,” Méndez told me. “Of course, Jade is surprised the first time. She quickly subsumes that into the rest of her existence.”

“A big part of my challenge was writing those scenes. How can it be part and parcel of Jade’s regular existence as a middle-school kid trying to make friends, trying to get on the cross country team?”

As it turns out, magic is deeply embedded in Jade’s family. One way she realizes this is through a special heirloom: an obsidian mirror.

“Obsidian mirrors were used, were associated with the god Tezcatlipoca, who turns into a jaguar at a certain point in one of the stories,” Méndez explained. “I use the magic, in some way, linking Jade to things that are bigger than herself – to her family, to her family lineage, that family connection to Mexico.”

Reflecting on the primary source documents and artifacts that she drew upon, the author said, “I think teachers can do a lot with them, think of this book as a way to engage with students, young readers, to think about Mexican colonial history, Mexican art.”

“It is a story about stories,” Méndez said. “It’s also the real stone objects and books, things that we have a lot of historical and archaeological evidence about – as well as the living stories people tell to this day.”

Rich Tenorio is a frequent contributor to Mexico News Daily.